This interview is the next chapter in MundaneMag.com’s ongoing collaboration with Verdict Music—a series built to spotlight the minds shaping culture from the inside out: legacy-makers, boundary-pushers, and artists (and architects) of sound.

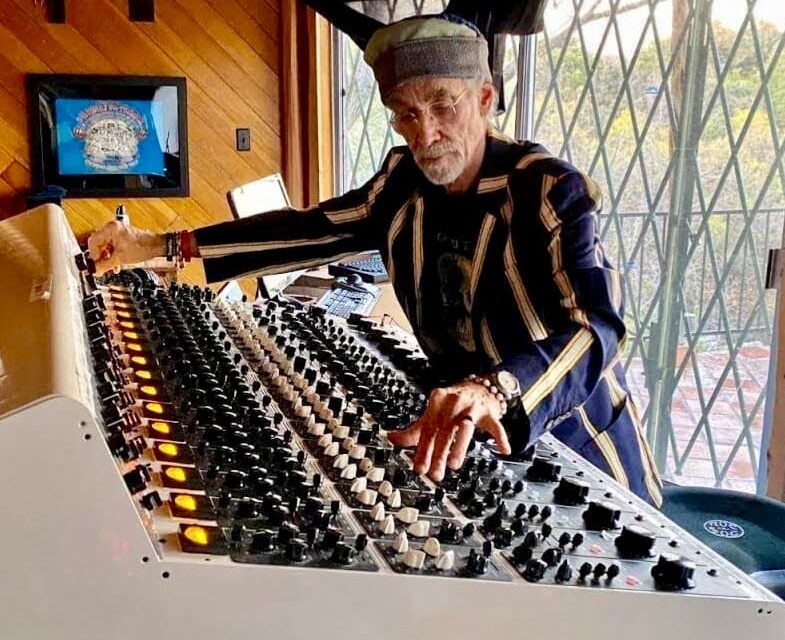

In this installment, we sit down with Rob Fraboni—producer/engineer, studio designer, and one of the rare figures whose career spans the mythic and the technical. From stories rooted in the orbit of The Band, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, and Rick Rubin, to a deeply personal 40-year mission to solve what digital audio took away, Fraboni walks us through his work on “Real Feel”—a technology he says restores the emotional participation of analog listening inside the digital era.

It’s a conversation about why the ear isn’t the only thing listening, why “clarity” can still feel empty, and why the best producers aren’t defined by fingerprints—but by the environments they create.

Q: Rob, how are you doing today? Where are you speaking to us from?

Rob Fraboni: It’s too bloody cold. But other than that, we’re good. I’m in Hudson, New York—upstate New York.

Q: Before we get into the legacy stuff, what’s going on with you right now? What are you focused on these days?

Rob Fraboni: I’m not really producing many records anymore. I do mixing, I’m doing mastering—but the main thing is this technology I worked on for 40 years that basically heals the issues that digital audio causes.

It makes digital audio feel like analog. Not sound like—feel like. Because emotion is what gets sacrificed the most when you go from analog to digital. Sound is another story. But the emotional engagement… that’s the big one.

Q: “Feel like analog” is a bold claim. What do you mean by that—what’s actually happening with digital audio?

Rob: This is super important to me. Digital audio uses pulse-code modulation—PCM. PCM was made for Morse code compression between the two world wars at Bell Labs in 1936. When they decided to do digital audio, they co-opted that. But it wasn’t meant for audio—and that was a big problem.

When you convert from analog to digital in PCM, the peaks get about 4 dB louder than the RMS—the average level. That’s why everybody has an issue with “brightness.” It’s not EQ. It’s not bass and treble. It’s those peaks. That’s why digital audio “pokes” you in the ear.

Q: You also connected that to streaming—like why people can’t hear dialogue in movies and end up using subtitles. How does that relate?

Rob: In streaming movies, the loudest things are sound effects and imported music—not the dialogue. When the peaks jump, those elements dominate, and the dialogue effectively drops. People think they’re getting old—“I need subtitles now”—but it’s not just that. I have a plugin for my TV with Real Feel and it fixes it.

Q: So the mission is bigger than music—it’s about how modern audio impacts the nervous system and attention.

Rob: Exactly. It made me able to listen to digital music again. I went off music when CDs came out. They wouldn’t hold my attention for more than a couple songs. In the old days you’d put on a vinyl album and you’d listen to the whole thing.

The best way I can put it: with digital, you’re an observer. With analog, you’re a participant. The emotional engagement doesn’t happen the same way with digital. It can—but it’s reduced. This fixes that.

“You’re always going to get resistance.”

Q: If you put this into the world in a big way—do you expect resistance from the audio industry?

Rob: You’re always going to get it. Engineers, people saying “you’re full of shit,” “nobody cares,” all of that. There’s skepticism—some of it is healthy—but I’m coming at this from a different direction.

Everybody else tried to deal with symptoms. I’m saying: go to the cause, fix it at the source, and all the symptoms are cured.

Q: Do you have a moment that proved to you this “feel” problem was real—not just theory?

Rob: I did a test early on. People told me, “Kids don’t give a damn about this.” So my son was in ninth grade—we made a CD with 20 songs. We put Real Feel on 10 of them, but didn’t say which. He handed out 20 CDs at school.

A couple weeks later, people said: “It’s weird—there are certain songs I really connect with, and the other ones I don’t.” The ones they connected with were the ones with Real Feel. These are high school kids.

Q: You also mentioned Keith Richards.

Rob: Keith Richards was the first investor in Real Feel. We talked about cause versus symptoms a lot. Fix the cause—everything downstream changes.

The origin story: 1980, the AES, and the “near riot”

Q: When did you first realize you had to solve this? What was the turning point?

Rob: There are two key moments. First: April 1980. We went to a demonstration in Santa Monica of the Soundstream digital tape recorder—two-track, not multitrack. Me, two other producers, and a few engineers.

We listened and thought: “Low noise floor, clarity—wow.” But walking out to the parking lot, one person said: “It’s cool… but something bugs me and I can’t put my finger on it.” And all of us agreed.

Then August 1980—Audio Engineering Society convention in New York. This is when all the new equipment is on the floor—digital multitrack machines were about to come out.

There was an Australian psychiatrist, Dr. John Diamond—he wrote Your Body Doesn’t Lie—and he was using muscle testing, measuring stress indicators with people wired up while playing music. One day he played a record and stress indicators went up 500% across the room. Over six weeks he realized: every time that happened, it was music recorded on the Soundstream digital recorder.

He wrote a white paper and presented it at AES. The guys designing those expensive machines did not want to hear anything was wrong with digital. It caused a near riot—security had to come in.

And when I walked out, I remembered that parking-lot feeling. I knew: we were right. There was something wrong, we just couldn’t name it yet.

Q: And then the “personal” moment hit you later—when you heard your own work on CD.

Rob: Exactly. 1985, I was Vice President at Island Records. I got my first CD of a record I produced. I took it home and listened and thought: “These are the mixes I did, but it doesn’t feel like it’s all there.” It got emotional—tears. Because I make decisions based on feel, not technical perfection. I felt like I was being cut off at the knees.

Fluorescent lights, the brain, and the path to “Real Feel”

Q: You said someone helped you connect digital audio to fluorescent lighting—what did you learn?

Rob: Dr. Robert Beck—Bob Beck—foremost doctor in electromedicine. He told me digital audio and fluorescent lights have an identical effect on the central nervous system.

Fluorescent lights flash 120 times a second—you don’t “see” it, but your brain reacts. Digital audio “flashes” at 44,000 times per second minimum. The brain doesn’t like that stopping-and-starting.

Beck explained that digital knocks your left and right brain hemispheres out of sync by about 5–7%. He gave me a brainwave entrainment device—magnetic field—set it to the earth frequency, and it brings the hemispheres back into sync instantly. Then muscle testing flips from weak to strong.

That was the road map. But it still took until 2009 to get something working—and it wasn’t finished then. The finalized version was completed and copyrighted recently.

Verdict + Rob: legacy, catalog, and what comes next

Q: How did you link up with Viv and Steve at Verdict—and what are you building together?

Rob: “We initially connected when they reached out to me a while back to mix & master a record of one of their artists. Ultimately though, we agreed that it wasn’t quite there yet but that opened the door to several other projects and we’ve been working together ever since”.

Verdict are amazing people. We’re talking about them helping take my legacy—and my work—and actually doing something with it. I never self-promoted. No manager. Everything was word of mouth for 50-something years. But this is a new time.

I can contribute audio quality, producing expertise, and Real Feel. And they have the ability to bring what I’ve built into the marketplace in the right way.

And we’ve got records that haven’t been put out—serious ones—that we’re going to put out through Verdict. One is Blondie Chaplin – The Fragile Thread. Another is Sir Mack Rice (who wrote “Respect Yourself” and “Mustang Sally”). We’re still figuring it out, but it’s going swimmingly.

For all inquiries, please contact info@verdictmusic.com.