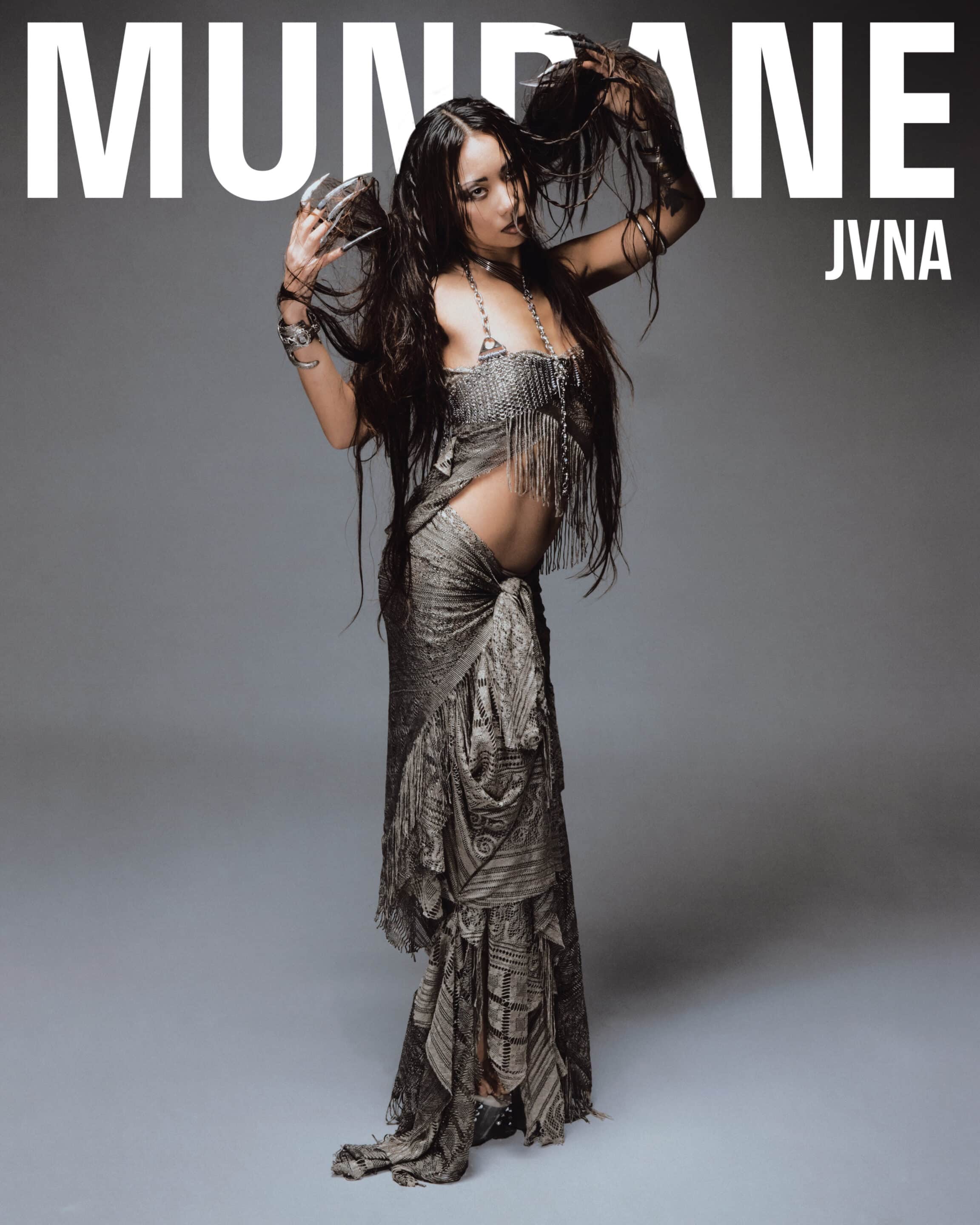

New York-based singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist JVNA is no stranger to transformation. A classically trained pianist turned producer, she spent years building her name in the melodic bass world. But with her latest release “Angels Falling,” she’s making a bold leap into alt-pop territory, shedding industry expectations and reclaiming her creative identity. This sonic journey will continue with the release of “Aphrodite,” her next single due out on August 8th.

We caught up with JVNA to talk about fear, freedom, what it means to evolve as both a musician and an artist.

Let’s start with “Angels Falling,” your latest release. What does this track mean to you?

“Angels Falling” is really about letting go—of expectations, of fear, of the boxes we put ourselves in. For years, I felt like I had to stick to what worked: melodic bass, EDM, that whole world. I built a career there, and there’s a lot of safety in that. But at some point, I realized I wasn’t growing anymore—I was repeating myself out of fear.

This song marks a personal and sonic transformation. It’s the first of many that leans more into alt-pop. It still has elements that are “me,” but it represents a willingness to fall—symbolically and artistically. Even if you fall from the sky, you’re still beautiful. There’s courage in descent, and that’s the message behind the track.

Was there a specific moment that triggered this creative shift?

Yes. I’ve been doing this since I was about 20—I’m 28 now—and I’ve changed a lot. I started this project in survival mode: single mom, Asian-American upbringing, no backup plan. There’s so much pressure in our culture to play it safe. Even choosing music as a career was risky, but I still clung to stability in my choices.

Eventually, I felt like I was dying creatively. I was successful, but unfulfilled. And I realized: I can’t keep making the same kind of track just to stay in my lane. It wasn’t honest anymore. So this new era? It’s about freedom.

How does your cultural background play into this artistic journey?

Growing up Asian-American, you’re often taught to follow structure—listen to your elders, keep things safe, make money, don’t rock the boat. I internalized that hard. It shows up in my need for stability and perfection. Even when I went into music, I still operated with that same mindset: “don’t take too many risks.”

But that mindset was holding me back. I had to unlearn that safety equals success. Now, I’m embracing experimentation and letting go of expectations—even my own.

Musically, what inspired you to move toward pop and alternative sounds?

Honestly, rebellion. I went from classical conservatory to EDM because I craved contrast. I’ve always wanted to do something different.

EDM culture, especially producer circles, can be rigid. There are rules about mix quality, loudness levels—people love to mansplain. I never really cared about having the “cleanest” mix. I care about emotion, about vision.

Artists like Grimes, FKA Twigs, Caroline Polachek, Snow Strippers, Earth Eater—they all inspire me because they prioritize artistic impact over polish. Their mixes might be raw, but the emotion is undeniable. That’s what I want to chase.

How do you typically approach a new track? Is there a set process?

It changes with each era. Early on, it was piano-driven—I’d sit down and just play. But lately, it’s more top-line focused. I care about strong hooks and building the production around the vocal.

Coming from EDM, I had to unlearn the idea that more layers = better. Pop can be minimal and still powerful. Sometimes it’s just a voice and a bassline—and that’s enough.

You mentioned collaborating more recently. How has that changed your process?

My first two albums were all me—writing, producing, everything. A lot of that came from wanting to prove myself, especially as a female producer in EDM. There’s a toxic pressure to “do it all” or be discredited.

But now I’m more open. Collaborating doesn’t mean you’re less of an artist. In fact, knowing when to bring someone in makes you a better one. The people I’m working with now aren’t just co-writers—they’re friends who understand what I’m going through. The songs come from shared experiences, not just sessions.

That’s a powerful shift—from proving yourself to owning your space.

Exactly. There’s a big difference between being a good musician and being a good artist. Being technical is one thing. Being able to translate emotions into a visual or sonic world? That’s art.

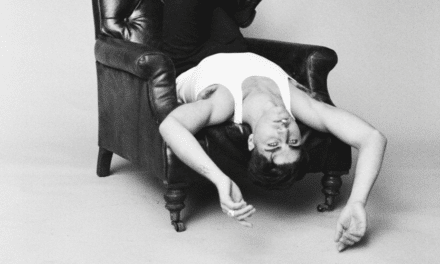

Speaking of visuals, your aesthetic feels very cinematic. What’s inspiring that side of your work right now?

Lately, I’ve been pulling from surrealist cinema. I love ‘Mulholland Drive’ by David Lynch, ‘Valerie and Her Week of Wonders,’ ‘The Cell with Jennifer Lopez,’ and ‘The Holy Mountain’ by Alejandro Jodorowsky.

I’ve also been trying to spend less time on social media. Algorithms feed you what’s popular, not necessarily what’s meaningful. I’d rather seek out strange, beautiful art on my own terms. It’s slower, but it’s more honest.

Would you ever score films again, given your background in film composition?

Absolutely. I studied film scoring in college, and it was my original plan. Even now, every time I write a song, I’m already picturing the video or the world it lives in. Scoring might not be the focus right now, but it’s still part of how I think creatively.

Looking back at your debut album ‘Hope and Chaos,’ how have you evolved as an artist?

That record was me learning in real time. My fans watched me grow—technically and artistically. Early on, I was obsessed with being a good musician: singing better, producing cleaner, DJing tighter.

Now, I’m leaning more into storytelling and visual world-building. I want each era to feel like a movie. I still care about musicianship, but I’m more interested in the whole experience now. I’ve become an artist, not just a producer.

Final thought—what does this new chapter feel like to you?

It feels like freedom. Like letting go of fear. Like falling—and trusting that the fall itself is beautiful.

Follow JVNA: