“Life in Paris is a bit of a double-edged sword. On one hand, you have this wonderful, strong art market and a great support system around it. But on the other hand, you are here because of that market, and so is everyone else, so you need to be truly extraordinary to succeed.”

“Great cities attract ambitious people” is the opening line of Paul Graham’s 2008 essay, Cities and Ambition. “You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.” It is only one of many contributions to the ubiquitous conversation about world metropolises and their respective energies. The media produces, and we repeat, countless tales of different lifestyles they encourage, cultural scenes they host, entertainment options they offer, and, eventually, personalities they attract. Whether or to what extent those stories are true is up for discussion, which is partially why you’re reading this paragraph right now. What is it exactly that makes for cities’ “greatness”? How do we define each city’s greatness? And most importantly, how do we differentiate between them?

In spite of our varying personal experiences, Paris will surely be listed among places with the most widespread and universally recognized myth. Vividly inhabiting the social imaginary on both sides of the Atlantic, the idea of Paris far exceeds the size of the city itself, which has an unimpressive area of just over 40 sq mi. Cramped, yes, but cramped with round café tables, bougie wine bars, small art galleries, and regular vintage furniture markets, one can easily see how Paris has come to be one of the most romanticized cities of the western world.

On the flip side of the Eiffel Tower, chic fashion, and fresh croissants, there is, however, another facet of the city that those manifesting a less enthusiastic approach towards it never fail to mention: exorbitant housing prices, dirty streets, rude people. Naturally, any big city is no stranger to successfully managing the coexistence of those two extremes without compromising their appeal, the latter attracting tourists and thus bringing in millions every single year.

Still, the case of Paris seems, in a way, particular: the Parisian myth is indeed so strongly rooted in our minds that the sense of disappointment it entails when compared with reality has given rise to a classified psychological syndrome. All of that is no news. Wherever you come from, you’ve heard about the good and the bad, the breathtaking and the disappointing, the glamorous and the soul-crashing.

Whoever comes to Paris with the idea to stay, it’s safe to say they assume the risks of the constant empirical swing living here implies. And yet, coming, they are. Numerously so. Young and ambitious international artists, creators, academics, and adventurers keep settling in the French capital, ready to have their dreams crushed but also relentlessly determined to make it work regardless.

If we are to believe Paul Graham and if cities indeed attract people that match their energies, there must be something that unifies those who ended up in Paris. Set on unraveling some common truth from the bemusing blend of exaltation and defamation, I followed that logic and talked to three creators living in Paris long enough to provide some hopeful insight into their own experience amidst the clichés.

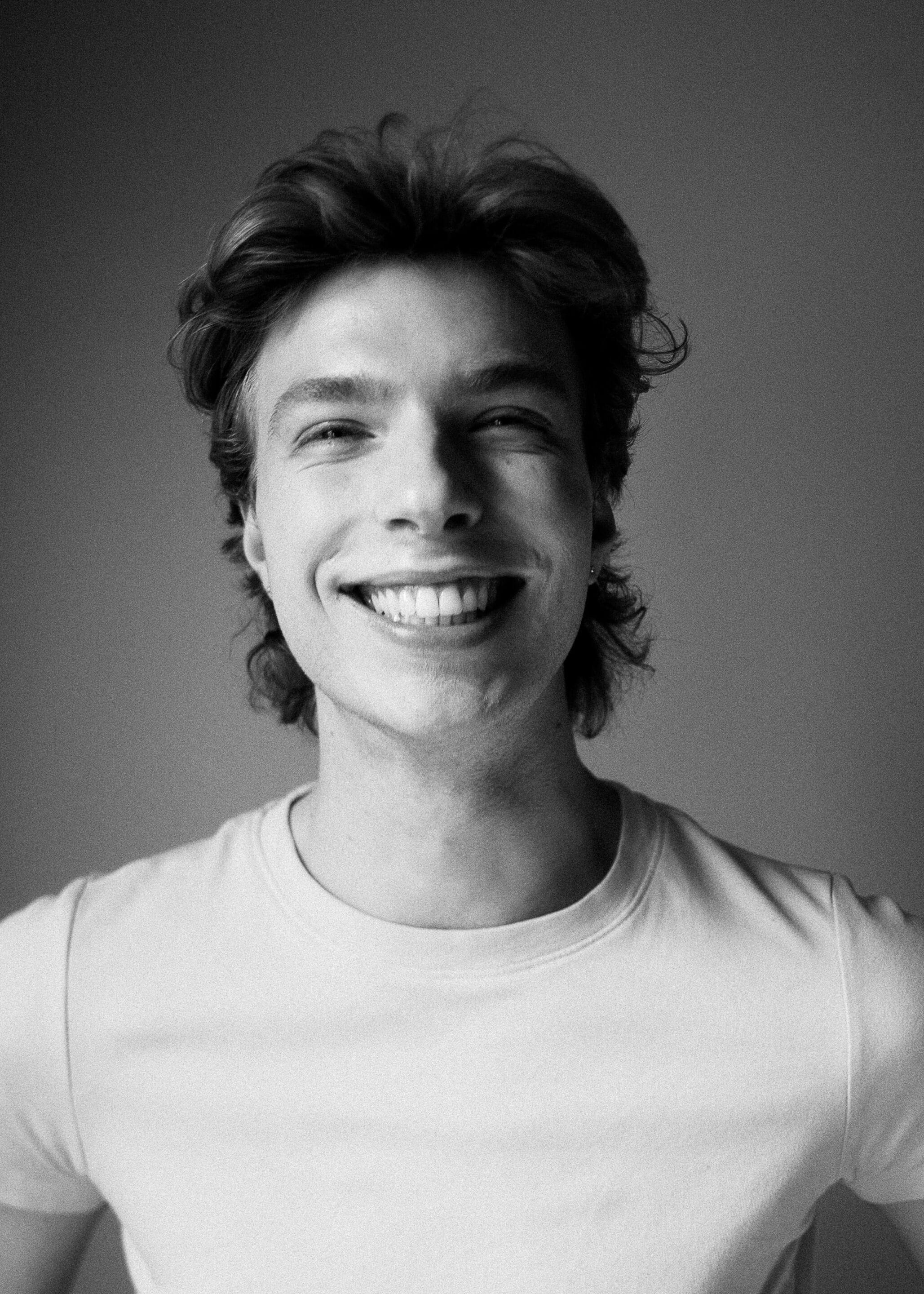

Hugo Deshusses is 22, French, and based in Paris for more than a year now. His professional activity, scattered between content creation, modeling, and communication, has made his social circle a heavily international one, which also happens to be his personal preference. He makes videos about funny stereotypes, truths, and little particularities of life in Paris, often featuring his international friends. Needless to say, he’s regularly exposed to cultural differences and contrasting opinions, understanding very well that what we expect to find in this city is rarely what we are faced with once we arrive.

“I’ve always been fascinated by cultural differences, traveling, and discovering new things. I used to live in Canada, and now that I came back to France, I continue to have this impression of discovering things because I only hang out with internationals. I think it’s fantastic. I can see my own country with fresh eyes.” Naturally aware of some ideas surrounding his country’s capital, Hugo admits that his foreigner-based environment has brought his attention to other, unexpected ones: “What I didn’t expect is that French people are perceived as way less open-minded than I thought we were. I heard, especially from Americans/Canadians, that they don’t feel as free expressing their way of being in terms of style. In Paris, we are known for the fashion, so I guess people would naturally assume that the street fashion is way more extravagant than it actually is. In reality, it’s a very specific, high-fashion, exclusive industry. If you don’t fit into some codes, your personal style won’t be as easily accepted.”

Parisian fashion, known for its distinguished sense of class and nonchalance—the crafted impression of looking sleek and sharp but somehow effortless at the same time—is indeed one of the labels the city prides itself on. So is, unsurprisingly enough, the subtle but persistent pressure to conform to it. To look like you belong in the Parisian streets is to be constantly faced with the absurd task of trying to replicate some pre-established taste that you can’t quite define while never visually showing that you’re intending to do so. “You know what we say in French,” says Hugo with a confidential laugh when I mention this dilemma to him, “if it’s too much, we don’t like it either.”

The culture of careful exclusivity translates into areas exceeding clothing choices as well. It is a common belief (confirmed by the majority of Hugo’s international friends) that Parisians are unpleasant, rude, and hermetic. On that point, my interlocutor disagrees. “I don’t think French people are deeply, genuinely not nice,” he says. “We are just very honest and straightforward, which is a very different conversation style than American sugar-coatingness. We don’t small-talk as much, which may be off-putting at first, but that doesn’t mean we won’t help you if you actually need help.”

Interestingly, he is not the only one to challenge the stereotype of Parisian brusqueness. Youssef Saidi, 23, a filmmaker in training who came to Paris from his native Tunisia four years ago to pursue education and a career in the film industry, admits that his initial impression of people in the city turned out to be entirely untrue.

“Sure, at first, it wasn’t necessarily the most appealing experience. And I had this image of Parisians, and of the French people in general, which I think is very widespread around the world: that the French are dissatisfied. Parisians are dissatisfied. They’re always protesting. They’re never happy with their government, and so on. But then I discovered that, in fact, there are a lot of kind people. Maybe Parisians aren’t necessarily the most welcoming at first; they can be very closed off. But then I realized there was a real sincerity to them, something you don’t find much elsewhere. The relationships you develop with people here are truly deep.”

Paris certainly wasn’t Youssef’s dream destination, nor his first choice. “I had this image of it as a rather unlivable city,” he says, “where getting around takes too long, and the people are unpleasant, so I really wanted to go to a different one.” But wanting to work in the film field, he knew that he would not find such opportunities anywhere else.

“When it comes to the film industry, everything in France is centered in Paris. I saw some statistics the other day: I think 90 or 95% of the film industry is based in central Paris. And it shows. There are tons of platforms and meeting places. Almost every week, I can go to one or two events where I can meet other people in my field and share ideas and find potential future collaborations. And also, since everyone is there and it’s not such a large industry, you end up making connections very easily. In fact, you get the feeling that the entire film industry is at your fingertips while staying in the same city, without having to constantly move around.”

What is striking here isn’t necessarily the field centralization, which is not unheard of in the case of this particular one (Hollywood comes to mind, rather overtly). It’s how reachable those possibilities seem, how accessible, how at your fingertips they constantly are. And that is driven by the very specific aspect of the city, namely, its space. Or the lack of, in this instance. Paris is a famously small city, and that means many things. Apartments so difficult to find and so little that it might seem unreal to an unaccustomed eye. Queuing to enter probably every single place of social interaction. But also the incessant feeling of never being completely alone. The imposed condition of space sharing is precisely what makes Paris so special, at least according to my third speaker. Davide Palmiotto, 44, is an Italian sound engineer and an artistic producer at the music production studio Alba Musique. He’s been living in Paris for almost 6 years now and is still magnetized by the city’s unique spirit of exchange and creation that, to him, is mainly due to this impression of spatial condensation.

“Among the biggest European cities, Paris is one of the smallest ones. You’re never alone in this city. There are people everywhere at all times, in the morning, at night, and on weekends. What I mean is that Paris pushes you to say, “OK, if you’re here, you have to do something.” Otherwise, there are 20,000 people every morning ready to jump right out at you. You have to push through. You can’t remain passive. You have to be truly present in the moment, and you have to move.” Which is to say, the city doesn’t only offer great possibilities in terms of cultural and artistic experience. It quite literally forces you to seize them, unless you want to spend your days in your 200 sq ft apartment with a plumbing problem.

To live in Paris, small and squeezed but also vivid and spirited, is to be aware of the space that surrounds you. Painfully so, since nature is almost nowhere to be found. “I was born by the sea in southern Italy,” adds Davide. “So, I already come from a place where I have a very strong connection with nature, a very strong connection with a wide horizon, something impossible to find in Paris. It’s an important change in visual terms, too.” The good news is, the urban surroundings so impossible to escape also happen to be absolutely stunning.

“As for the clichés regarding the beauty of Paris,” says Youssef, “I, for one, think they’re true. Paris is a very, very, very beautiful city. I’ve never seen a large city that’s as beautiful as Paris, in the sense that, most of the time, the architecture is truly quite unique. There’s a huge amount of heritage that has been preserved.”

For Davide, it’s not only the superficial beauty itself; it’s a sensation that feels more transcendental: “There is a very thrilling culture here; it’s like an energy. This idea that if I come home and after 10 minutes I feel like going out to see something spectacular, I can—it’s always within my reach. I can leave and be face-to-face with something special right in front of me. It’s obviously something artistic, something architectural, but also something fleeting that happens in that very moment. Every big city has its own energy, and I find that in Paris, there’s something about the light, about the grandeur of things. That’s its energy.”

Maybe this energy is what others have felt as well. Maybe that’s why the city has always been a shelter—or a chosen battlefield—for artists. Maybe that’s why it still is. But as with all the other overblown components of the romanticized myth of Paris, this one, too, has its down-to-earth, socioeconomic explanation:

“In France, there’s a support structure for creative work that’s very advantageous compared to other countries,” explains Youssef. “The French art system is state-run: the state provides subsidies, the financial means to create, which gives new talent a lot of space to emerge. That’s something unique in the world. We also have an intermittent employment system that allows people to continue receiving state benefits during periods of inactivity, because our profession isn’t one where we necessarily work all the time. That’s a huge advantage compared to other countries.” An advantage that doesn’t come without its consequences, because we see quite well already that in this tricky fairy tale, if something seems too good to be true, it probably is.

“Politically speaking, France is the only country in the world with a specific status for artists. And so, this naturally enables many people to express themselves, live their lives, and earn a living. But actually, that’s a bit of a double-edged sword as well. On one hand, you have this wonderful, strong art market and a great support system around it. But on the other hand, you are here because of that market, and so is everyone else, so you need to be truly extraordinary to succeed.”

So there you go again, the pressure of achieving greatness, apparently a prerequisite to survival in this city of the highest highs and the lowest lows, enthrallment and disappointment, daily burden and occasional chic. It seems like if you’re determined to fit in, your lifestyle must match the level of contradiction and extreme that Parisian appeal truly consists of.

So the remaining question is: is it all really worth it? Even officially recognized and economically supported, even pushed to the limit of creative effort by the bittersweet cocktail of endless possibility and peer pressure, one still finds himself squeezed in a bus on a rainy Monday morning, overpriced coffee in hand, between thousands of other trench-coated individuals questioning their choices. Wondering if their lives are really that glamorous, what this Parisian dream even is, and why it feels so unattainable, despite all the effort.

“I think it’s part of the fascination people have for France, to be honest,” concludes Hugo when asked to share his understanding of the myth around the city. “I think they like that unreachable aspect. Just like in a relationship, when someone is playing hard to get. It makes you want them even more.”

We’ll probably never fully understand it, even if we’re fully living it daily. In the end, the Parisian dream is exactly that: a dream. The realization of it is always rougher around the edges than the bubbly idea in your head. But somewhere in the process of chasing it, a dream becomes a goal, and Paris becomes a tool to achieve it. So it starts to function as any other tool: we’ll put up with all the confusing and annoying parts as long as it serves our purpose.