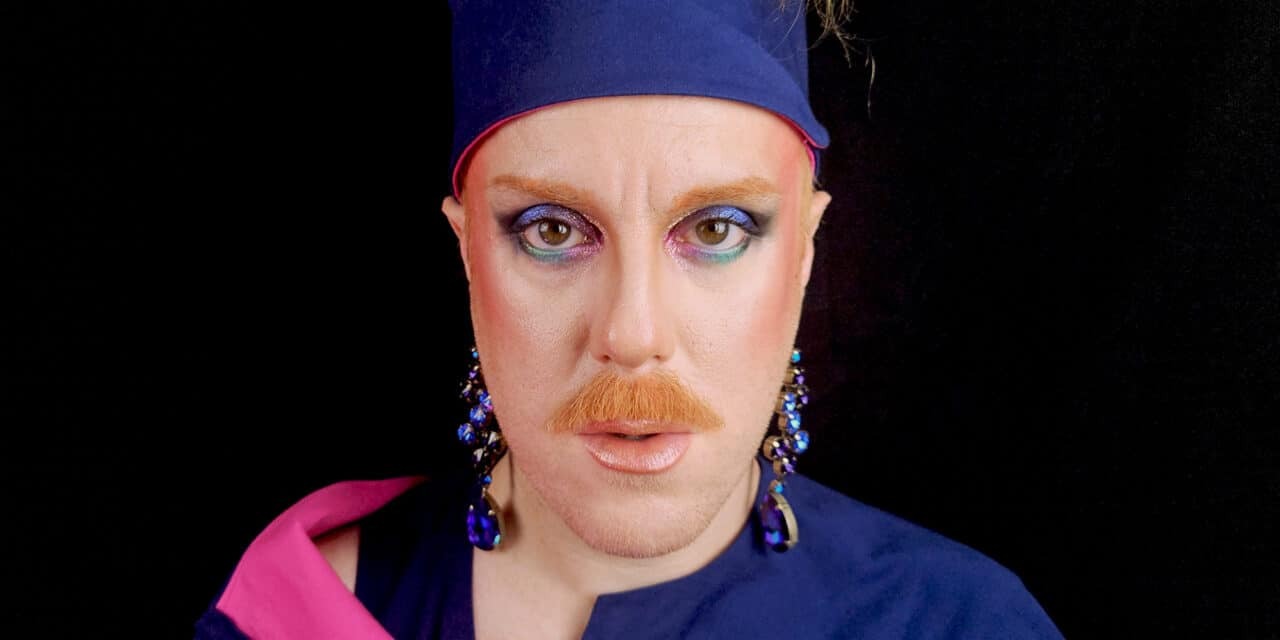

New Orleans-based multidisciplinary artist Chris Giarmo—best known as the mustachio’d standout of David Byrne’s American Utopia—is stepping into a new chapter. Today, Giarmo unveils Boys Don’t Fight, an eponymous debut album arriving October 17, along with its first single, the sweetly chaotic “The Megaman Song.”

From Stage Spotlight to Studio Vision

If you’ve seen Byrne’s American Utopia (on Broadway or on tour), you’ve already seen Giarmo’s magnetic pull—Vulture once called him “impossible to take your eyes off.” Beyond the stage, he’s collaborated with icons like Taylor Mac and Annie-B Parson, performed at The Sydney Opera House, Coachella, Red Rocks, and The O2 Arena, and composed sound for experimental theater luminaries including Tina Satter, Faye Driscoll, and Young Jean Lee.

And then there’s Kimberly Clark, Giarmo’s drag alter-ego who carved a unique corner of YouTube culture with anti-consumerist beauty critiques and the infamous “anti-haul” videos. This project, however, feels like the nexus of all those worlds—equal parts theatrical, radical, and deeply personal.

Riding the Waves of Boys Don’t Fight

Listening to Boys Don’t Fight feels like tumbling through waves: disoriented, breathless, but alive. These songs—dense with lyrics, packed with revolution, queerness, and a touch of gamer nostalgia—capture the tension between chaos and intimacy, between collapsing systems and the search for self.

At its heart, the project asks: what does it mean to find yourself, and one another, in the turbulence of late-stage capitalism? The answer comes not through manifestos, but through exhilarating electropop hooks that carry both sweetness and bite.

“The Megaman Song”

The first single, “The Megaman Song,” is perhaps the album’s most deceptively simple moment. Built on the metaphor of a 1990s video game robot boy—learning skills by defeating enemies—it’s about the impossibility of being everything for someone you love, and the tenderness of being human instead. Sweet, earnest, and a little surreal, it sets the stage for an album that promises both playful surfaces and deeper undercurrents.

A Queer Electropop Manifesto

For Giarmo, Boys Don’t Fight is more than an album; it’s a space. A place where queerness, joy, and resistance can dance together. A soundtrack for connection in uncertain times. And with “The Megaman Song” leading the charge, the countdown to October 17 feels like the beginning of a movement—one that’s as theatrical as it is cathartic.

Your debut as Boys Don’t Fight feels both intimate and expansive—like electropop crashing into theater and drag. What was the spark that told you this needed to become its own project?

I’ve been writing and performing my own songs for decades now, but the spark to legitimately record and release them came while I was on the road with David Byrne’s American Utopia tour in 2018. That gig was a culmination of so many different career trajectories for me and showed me the songs I was writing didn’t need to live in isolation from the other types of performance I could do.

You’ve performed on some of the world’s biggest stages with David Byrne, Taylor Mac, and Annie-B Parson. How did those experiences shape the way you approach something as personal and vulnerable as this debut album?

Honestly, I think it’s been performing in tiny drag bars, black box theaters, and other small makeshift venues that have really given me the confidence to be able to share something so intimate with an audience. I always try to recreate that intimacy with whatever audience I perform for—even if they’re thousands of people out in the dark at Red Rocks, on Broadway, or at Coachella. I’m not one to shy away from eye-contact—really seeing people and being seen, and I hope that the folks that have found me through all that amazing exposure feel that connection.

The description of Boys Don’t Fight—like being tossed in the ocean, weightless but pummeled—captures both joy and danger. How do you translate that duality into your songwriting?

For a lot of the tracks on this album, the production feels like as much of a part of the songwriting as the music or lyrics. I come from a theatrical sound-design background, so as I’m writing songs, I’m also hearing the multi-dimensionality of the vocal arrangements and instrumentation. I like my songs to feel like some kind of 4-D theme park ride—an element of safety, being strapped in and on track, but also a swirling environment of chaos enveloping you at all times.

“The Megaman Song” uses a video game character to talk about love and limitations. What drew you to 90s video games as a storytelling device, and do you see nostalgia as a tool in your work?

It’s just what I grew up with. I’m an “Xennial” so a lot of my world view was fomented at this super-specific, turn-of-the-millenium technological cusp. But I also think there’s something so eloquent about just how much those pre-Y2K,16-bit games could hold with such limited pixels and soundcards. I was recently playing Final Fantasy IV (II in the US) and found myself so moved by this moment of sacrifice these two brothers make mid-game. There were no special effects or epic sound design but so much was communicated with such a limited palette. It makes me think of the concept of “poor theater” as coined by Jerzy Grotowsky, whom I studied while at the Experimental Theater Wing at NYU.

Your drag persona Kimberly Clark introduced the world to the “anti-haul”—a radical rejection of consumerism. Do you see Boys Don’t Fight as another form of resistance against late-stage capitalism?

I’d say Boys Don’t Fight is my creative and inquisitive response to existing in this current global capitalist state. Kim’s videos are prescriptive, and my music feels more explorative. But yes, I can’t help but resist the the systems that perpetuate oppression, exploitation and genocide with every fiber of my being—including my money, my voice, and my art.

There’s queerness at the heart of this project—not just as identity, but as a way of seeing and feeling. How does queerness guide the emotional and sonic world of Boys Don’t Fight?

You mentioned the idea of ‘expansiveness’ before and I think that’s the thing. Holding multitudes—identities, sounds, genres, concepts—feels inherently queer, but also inherently human, or like, fulfilling the potential we all have as humans.

With such a multidisciplinary background—dance, theater, drag, music—do you see these songs as existing beyond the record? Could they evolve into stage works, performances, or something more hybrid?

Yes! I’ve been developing a concert version of this album for a few years now with choreographer Elizabeth DeMent and production designer Douglas Green (both of whom also worked on American Utopia). There will be dancing, and amazing lights, and cute outfits.

The album navigates themes like revolution and acceptance, but always through a deeply human lens. Was there a specific personal moment or turning point that made those themes unavoidable for you?

So many moments, but the come-down from the 2018 tour really did change my life. I’m super grateful to have been able to land in New Orleans after that. This town makes it really easy to honestly connect to humanity and truth (well, if you let it) and I’m proud to call this place home.

Collaboration has always been central to your career. From Byrne to experimental theater to this record—what’s the difference between lending your energy to someone else’s vision and building your own universe?

I feel so comfortable and focused when I’m not the boss—like I always know just what to do to solve someone else’s problem, or translate something someone else wants to communicate. That’s just the way I am: a fixer, a translator, a giver. When I have the final say, it can be incredibly difficult and confusing to know what’s “right.” But that’s forced me to stop focusing on perfection and just make what I make, because, well, that’s all I can make. Taylor Mac always says, “perfection is for assholes.” This album has forced me to practice that preaching!

Boys Don’t Fight lands at a time of cultural exhaustion and reinvention. What do you hope listeners take away when they let themselves get “swept under” by these songs?

I hope the journey this record might take you on is a challenging and imaginative one. I’m a queer person that writes songs from a queer experience. If you don’t share that experience, you can do what I did when I heard all my favorite songs growing up: use my imagination and make it about me. But know that this record might not be about you. Instead it might challenge you to embrace the nuance and specificity of a different individual’s experience, which is a kind of coming together that the current isolationism of white-supremecy and global capitalism desperately tries to prevent.