Tragedy, I’ve been told, pulls us together. Think of all the people lining up to donate blood after 9/11! The volunteer firefighters who face raging wildfires, the neighbors stacking sandbags together to fight floods! Remember the great Northeast blackout of 2003, which left New York City and large chunks of the country powerless; instead of looting or descending into full-on Purge-style anarchy, stores handed out free ice cream and people chatted with their neighbors from lawn chairs. Global crises remind us of our shared mortality, and inspire us to be more civic-minded versions of ourselves.

To this I say: [Extended jerk-off motion]. Tragedy can inspire us to be kinder, or braver, or to hand out more free ice cream, but not for long. In times of great need, we draw close to our community, but communities are made of people, and people are trash monsters cobbled together out of petty grudges, selfish desires, and opinions about TV. Thus, in the midst of a mass crisis, we often begin by tending to our neighbors and end up by competing to see who has the worst pain.

When the coronavirus hit, my social feeds and circles were initially an orgy of mutual concern. We gave each other coping tips and helpful infographics, sent phone numbers around, taught each other how to order groceries. A few weeks later, though, the fractures were showing, as our experiences divided along familiar lines: The childless vs. the parents.

These two groups not-so-secretly resent each other at the best of times. When daycares closed, schools shut down, and playgrounds were no longer an option, that resentment escalated to Cold War levels. Every parent I knew was sending anguished messages to the others — what was it like to know silence? To feel rested? To not fear for your job? To reach the end of your to-do list? To watch a movie or read a book or hold an adult conversation or, or, or?????? — and quietly backchanneling rage at childless colleagues and friends for having the gall to complain about how bored they were while binge-watching TV and meeting work deadlines.

The childless folks stayed polite for a week or two, but soon, their real feelings leaked out: Why were the parents being such martyrs? What’s so hard about taking care of a kid, and why should it inconvenience anyone else? What’s with all this “you don’t know what it’s like” and “you’re lucky” and “seriously, I am doing 24-hour-a-day labor for someone who cannot manage their own emotions or self-entertain for more than ten minutes and who may in fact be traumatized if I focus on my own needs” crap? Why even have kids, if you’re going to complain? “Us childfree folks are all on blissful perma-holiday because we made different decisions,” my excellent friend, Rue Morgue editor Andrea Subisatti wrote to me, describing the fights she’d been having lately. “Who knew?”

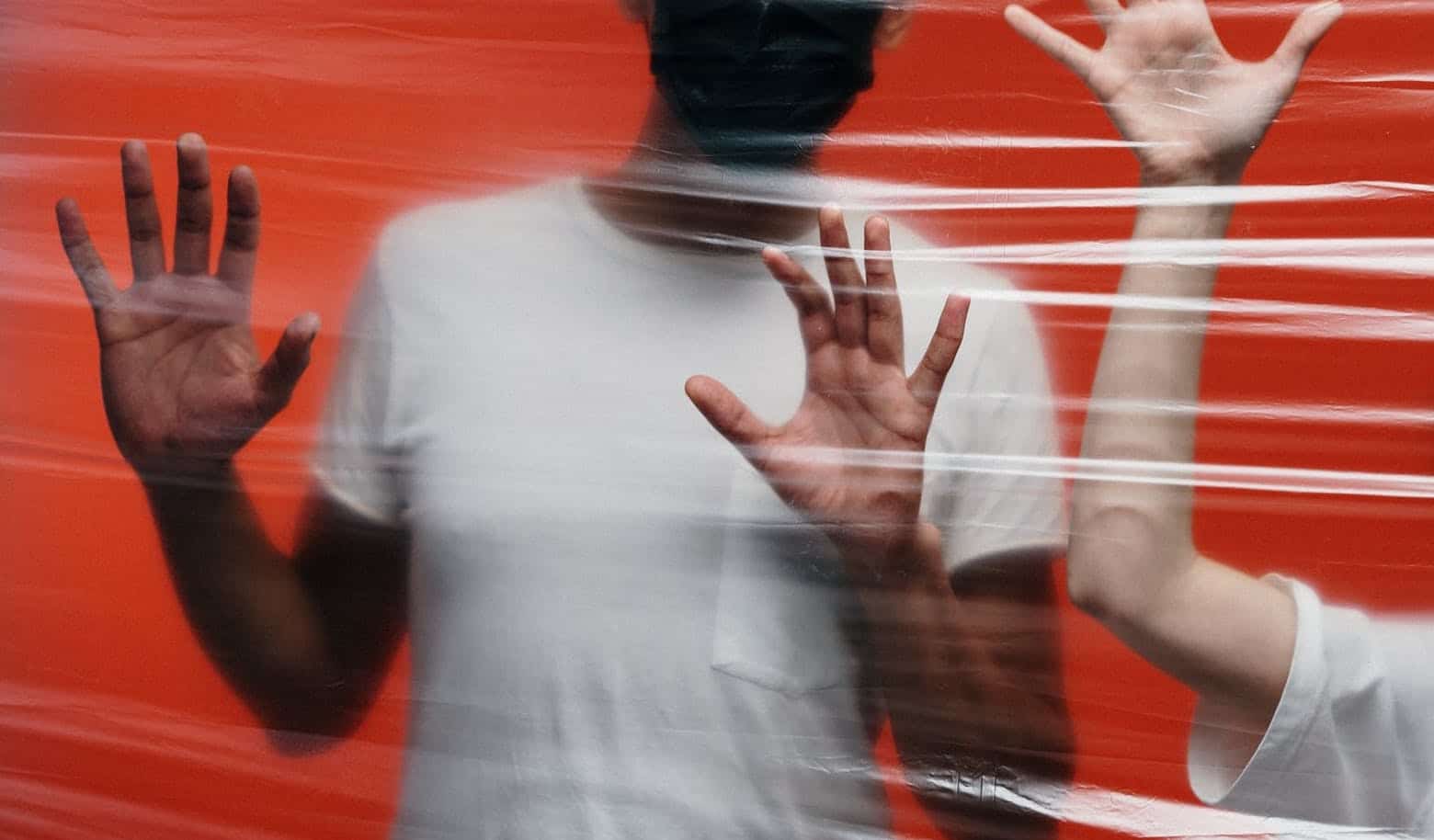

The only thing preventing a murder, under these circumstances, was the fact that we could not touch each other — though, thanks to the wonders of social media technology, I did manage to have some relationship-ending fights. The non-moms were furious at being told that their own loneliness or infertility or anxiety or unemployment was the easy version; tired of having their pain perennially discounted. I was at the end of my rope — freelance outlets folding, invoices going unpaid, emergency room visits, and, oh, yes, a goddamn two-year-old — and furious that they expected to be coddled when I barely had enough energy left for myself.

All of us were right. Our psyches are built to handle individual crises, not the reality of everything going wrong for everybody all at once. We are each the protagonists of our own reality, programmed to save our own lives before we shift our focus to wider problems, and thus, our own problems often look bigger and more real to us than anyone else’s. My childless acquaintances and I believed we were in the worst possible situation — which was correct, for our own given values of “worst” — but every Hell, including this one, has multiple circles. We may not all be broken in the same ways, but pain is pain.

It’s not just moms vs. non-moms. A woman tells me that, whenever someone complains in her private Facebook group for teachers, someone pipes in to shame them for forgetting the plight of the students. Another woman is living in a house with seven people, including a 16-year-old and some household members with disabilities; the 16-year-old is confident she has it worse than anyone, and everyone else has learned to stay quiet.

The coronavirus pandemic has created an endless assortment of worst-case outcomes, like a game of “Would You Rather” from the makers of Saw: Would you rather be quarantined with rowdy three-year-old twin boys, or isolated in a one-bedroom apartment with no human contact? Would you rather lose your job with no hope of finding another, or be forced to leave the house every day to do “essential” work without protective equipment? Do you want to be stuck indoors with a partner you planned on dumping, or be single and unable to date for the foreseeable future? Do you want to see your parents die, or be trapped in a home with abusive parents? Would you rather be the childless cisgender woman whose IVF was canceled, or the dysphoric trans man who has to indefinitely delay top surgery?

Do you want to die? Because people are dying. In all of the above scenarios, you’re alive, so what right do you have to complain, you selfish monster?!

You have every right, and you always will. None of the above should be happening; all of it is unbearable. It is also, probably, inevitable that we will have petty fights with each other; we’re all experiencing grief and “anger” is famously one of grief’s stages. Yet in an apocalypse this multivalent, it’s almost impossible to fully process the extent of the damage. We are all experiencing the same problem, but it looks different in every household. Thus, when you’re having the worst day of your life, it becomes tempting to assume that this would be the worst day of anyone’s life, and that you are the person being most affected by the mass trauma.

Telling each other to toughen up or stop complaining doesn’t help, either. The fallacy of relative privation — “A is worse than B, therefore B is not bad” — is not a recognized therapeutic tool. Not only does it generate nonsensical arguments (being non-fatally stabbed is better than being fatally shot, but that doesn’t make being stabbed a desirable experience) it teaches people that they cannot ask for empathy unless they can prove they’re having a worse time than anyone else, and thereby creates a vested interest in dismissing or diminishing other people’s pain. Compassion need not be a limited resource, and when we start rationing it, people immediately start strategizing how to cut in line.

I am not telling you to pull together in this time of crisis, or that it’s going to bring out the best in you or anyone. Humans are power-hungry chimps with iPhones, and disaster doesn’t change that. The history of civilization is just people trying to find some way to constrain ordinary human selfishness, and most of the constraints we’ve invented — religion, law, abstract concepts like solidarity or patriotism — don’t really work. Yet we have been able to imagine our way into empathy, at times, and that act of imagination has given us all the gentleness we have. When our pain is overwhelming, we can let it overwhelm us, and try to feel some pity for the lost, dazed survivors we’ve become. We can also imagine that pain, just as real and huge and urgent, radiating from inside our neighbor’s skin.