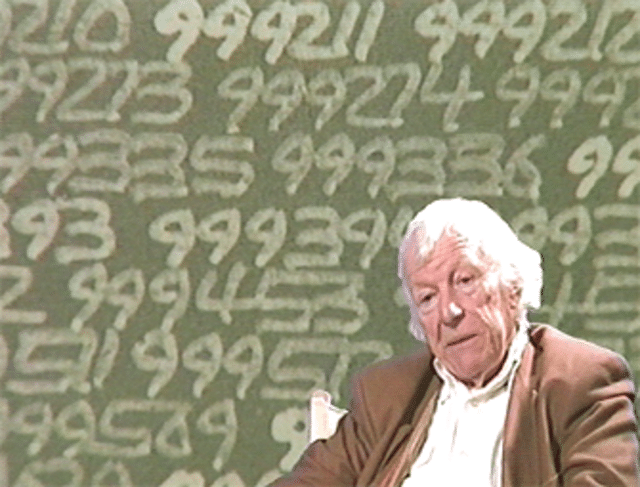

Man has made (futile) attempts at defying mortality from the beginning of human history. Perhaps we all grasp at the lives that we all must acknowledge as fleeting. Polish-French artist Roman Opałka, though, made his attempts indisputable as such. Born in 1931, Opałka didn’t realize what would become the defining piece of his life until well into adulthood, in 1965. Beginning in that year, he started his magnum opus, as a series titled 1965/1-∞. From that year until his death in 2011, Opałka completed 233 canvasses to add to this series. And what a grandiose series it is!

Over the course of its inception, 1965/1-∞ was an ambitious project. Fundamentally, it was a grab at capturing infinity: each canvas–or “Detail”–is a monochromatic count-up. Starting at “1”, Opałka used a minuscule paintbrush to enumerate upwards, and he never stopped for the remainder of his life. As he painted, Opałka recorded himself counting in his native Polish.

From 1968 onwards, he also took an auto-portrait after he completed it; each photograph is usually displayed alongside its respective Detail. Sometimes, the exhibition space of certain Details will also play Opałka’s voice recordings, though not necessarily the ones that correspond with the displayed pieces. Further, some of the recordings have been re-assembled, so the numbers aren’t even in order.

By the time he passed away, Opałka had counted over 5.5 million. Over the course of the series, the background of each Detail became lighter, starting at a deep black, and eventually a stark white; he painted using white, as well. Therefore, as time went on, Opałka would paint white on white, the actual numbers barely contrasting with the canvas color. Through the auto-portraits, the viewer can see Opałka’s hair become white over time, his eyes becoming lighter, this tonal adjustment is only highlighted by the monochromatic composition of the neighboring Details.

In an ideal world, 1965/1-∞ would be viewable in its completeness as the monolith that it is. If this were the case, then Opałka’s aging would be effectually witnessed by viewers; shifting shades of each Detail would be conspicuous, and the sound of Opałka’s voice would complement the observable numbers.

In actuality, different museums possess a small number of Details each. A couple of years ago, I saw two Details painted years apart, at the Museum of Contemporary and Performance Arts in Warsaw. Notably, the Guggenheim in New York City possesses a single Detail: “1965/1–∞ Détail 1520432–1537871.”

When describing 1965/1-∞, Opałka characterized his masterpiece as “a single thing, a single life.” It’s no wonder that he did, considering that as the numbers progress higher, Opałka’s image visibly deteriorates. The majority of his life was given up for this piece of concept art.

Yet, it has only ever been on display as a fractured version of Opałka’s effort. While this fact is something of a tragedy of aesthetics, it comes as no surprise that putting all 233 Details on exhibition is not at all practical. Still, the inability to visualize this piece as a singular vignette hinders adept interpretation.

In the past decade since Opałka’s passing, though, modern technology has progressed extensively, perhaps to the point of bringing a more comprehensive exposition to his inquiry of the infinite. Within the past year especially, given the inaccessibility of museum and physical art spaces, the notion of the digital art space has come to the forefront of many a new media conversation.

Since 2015, virtual galleries for art museums have boomed in popularity. In the United Kingdom, the organization Art UK finished assembling a photographic catalogue of every piece of publicly owned art just last year. The concept of virtual tours, while somewhat established prior to 2020, has become far more popular (and resourceful, with the development of manipulatable, 360° displays); virtual reality projects have also seduced curators, like the V&A in London. As new forms of digitization further integrate into museum curation, the possibilities for frames of display are truly endless.

As the digital space becomes more complex, both inventive, electronic art, and more traditional, material art will have the capacity to be properly represented. The physical experience offered by the tangible art space can never be totally replicated by an interface, but, these interfaces do create opportunities for other layers of audience participation.

Through this participation we usher in another layer of interpretation. In a paper published by the Tate, “New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age,” author Charlie Gere expounds upon how the electronic reckoning of time and space in this kind of environment affects the art as it is viewed. While this modification of conditions can be a source of anxiety–as many creations of merit were always meant to be encountered in-person–it also presents an entirely new dimension for art exploration. As Gere explains:

The gallery is as performative as it is constative. It creates the past it supposedly simply shows by what it chooses to accept as a donation, to buy, to curate, conserve, and display. Thus it affects not just our understanding of and access to the past, but also our relation to the future by choosing the legacies that are available to us and to future generations.

A semblance of an erasure of time and space as we now understand them can, effectively, bring us closer to the art and closer to one another as we are arrested by that art.

And, in the case of Opałka’s 1965/1-∞, this implosion of time and space could provide a dynamic backdrop to the series. It has oft been construed as symbolic of the brevity of the human condition, a Wall Street International article describing it as a “grand metaphor for human existence and a deceptively restrained expression of the artist’s vitality and passion in the face of unstoppable evaporation.”

In that same article, “Roman Opalka: Painting ∞,” writer Lévy Gorvy theorizes that this series “stands as one of modern art’s most powerful and poetic inquiries into the mutability of time and the spirit’s response to it.” Time moves forward at its unrelenting pace, but things do not stay constant; even within this singular series, its elements shift. As the numbers count up, the canvasses change, and so does Opałka’s appearance in his auto-portraits.

Alas, these changes can only have impact of being viewed in the absence of time: incremental shifts of the hue of each Detail, of Opałka’s image, do not matter. It is seeing how staggering these shifts appear when bombarding the viewer en masse, simultaneously that they become powerful.

It is Opałka himself who once said, “Time as we live it and as we create it embodies our progressive disappearance.” Unfortunately, that disappearance can only be visualized in absentia; mortality is only resembled by the juxtaposition of a lifelong pursuit of timeless infinity laid out before us, finished but incomplete.