Among all the moments constituting the circular course of the year, the month of May is truly an interesting one. With days getting longer, fresh, warm air forcing itself in through the windows every morning, and the perspective of summer vacation approaching ever so faster, the experience of life becomes undoubtedly more bearable. It is, however, also a moment when indulging in newly rediscovered pleasures of life is constantly being hindered by the end-year reviews, summer finals, general fatigue accumulated over the year, and the fact that summer vacation, even if approaching, is not quite there yet. And it so happens that this bittersweet period is often chosen as the starting point of a number of annual art festivals. Starting around May and usually lasting throughout the entire summer – probably to make the visit easier for those who need regeneration after the late-spring stretch – these large-scale initiatives have recently seen something that we may call, if not an increase in popularity, then at least its stable and impressive maintenance. Photo festivals are no exception to this rule. For instance, this year’s editions of PHotoESPAÑA and Krakow Photomonth, both decades-old and internationally recognized festivals, couldn’t complain about the lack of social response: high attendance rate at openings, busy exhibition halls throughout the entire duration of the shows, and projects so interesting and so numerous one could only wish they had enough free time to see them all.

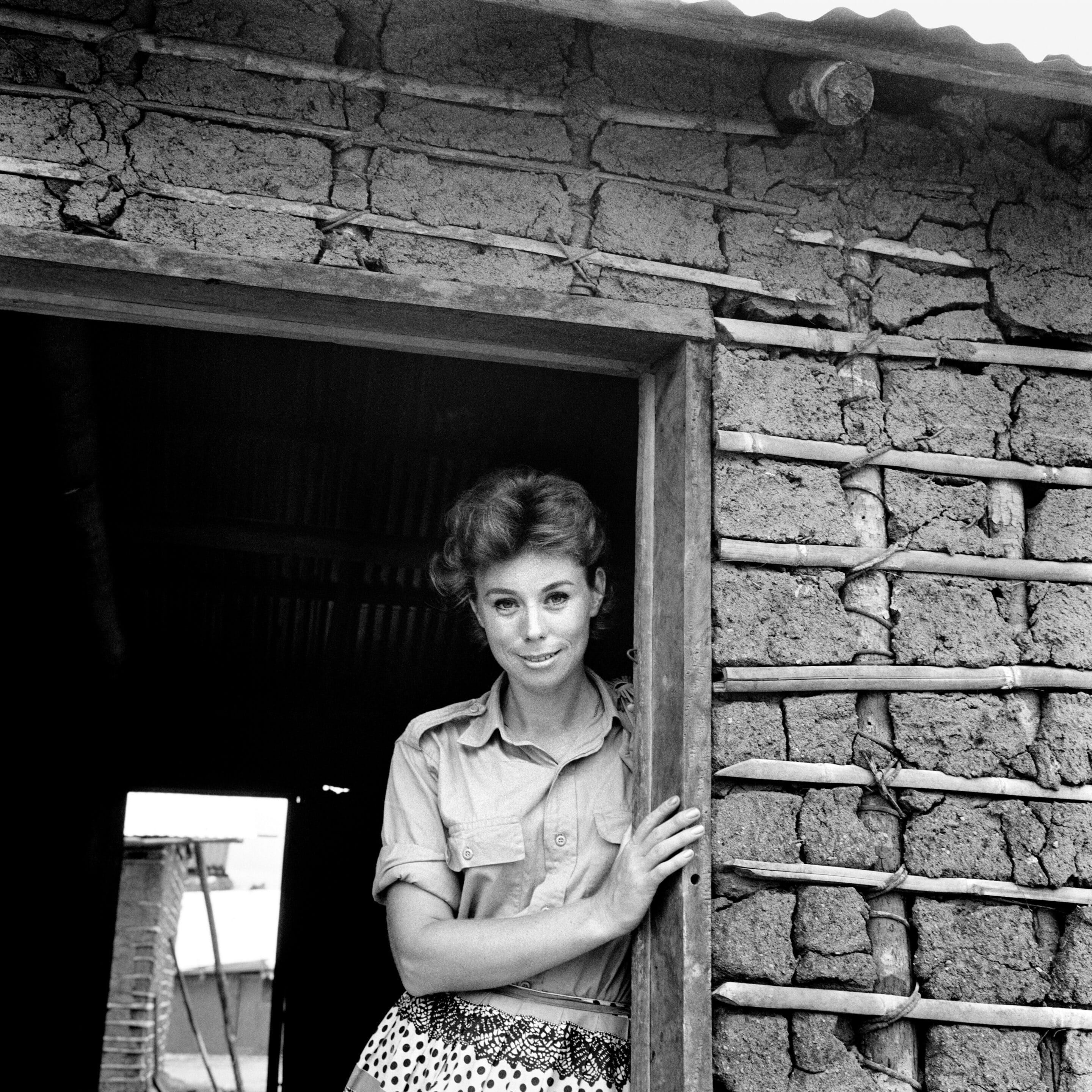

s/t. Barbara Brändli en Santa Maria de Erebato, estado Bolivar. 1962.© Barbara Brändli/Colección C&FE

Barbara Brändli, Baile del pijiguao, comunidad yanomami en Mavaca, Región del Alto Orinoco. Estado, Amazonas, Venezuela.1964-1965. © Barbara Brändli/Colección C&FE

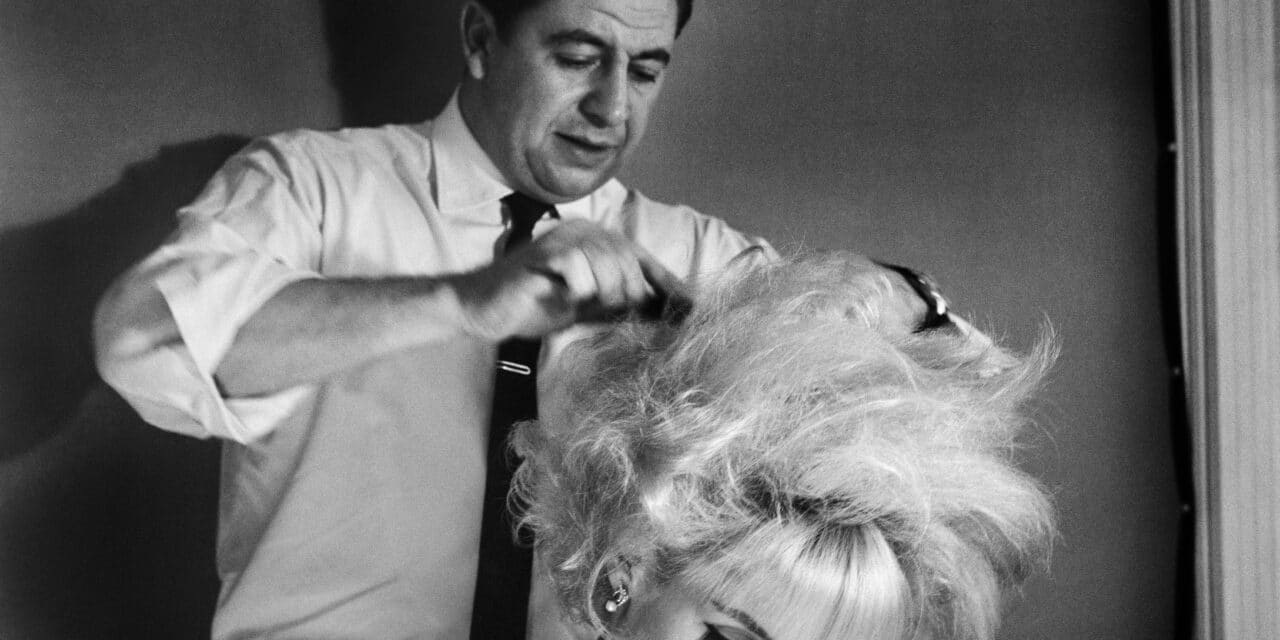

Barbara Brändli, Arturo Revlon. 1964. © Barbara Brändli/Colección C&FE

What I find most captivating about those shows is not so much their multiplicity or the renown of their authors as it is the variety of forms and subject matters they cover. The diverse nature of the exhibits and of the photos themselves definitely calls for praise for the team of researchers and curators behind the projects, their selection process seemingly dictated by everything but repetitiveness, but it also raises the fundamental question of what a photo actually is and what it can convey. Photo festivals usually hold tens if not hundreds of different exhibits, the scale of which ranges from small, few-picture installations to huge undertakings, the tour of which takes a couple of hours. They are either collective shows or in-depth profiles, and the authors are either up-and-coming young creators or established and acclaimed artists. In short, no factor is fixed, and any combination is possible. One may think the organizers don’t want to bore the audience, hence the large spectrum of variations, and one probably wouldn’t be entirely mistaken. But the very nature of a photograph as a medium plays a pivotal role in this puzzle, as it is this nature itself that even allows for such versatility. And it is this same nature that is responsible for the undiminished public interest and the special role photography seems to be playing in social life.

Cristina García Rodero El peliqueiro. Laza. Galicia. Spain. 1975. © Cristina García Rodero | Magnum Photos

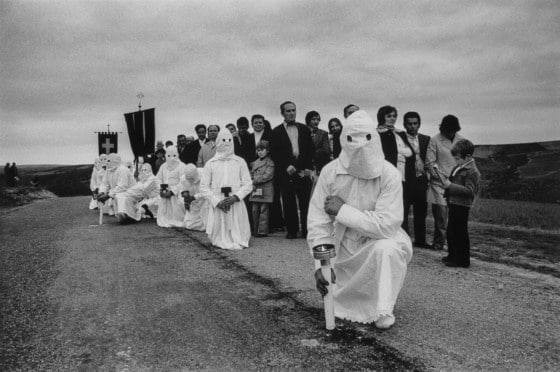

Cristina García Rodero Confreres de la Croix, Bercianos de Aliste. Spain. 1975. © Cristina García Rodero | Magnum Photos

Cristina García Rodero The strengths of the soul. Puente Genil. Spain. 1976. © Cristina García Rodero | Magnum Photos

Namely, this purely digital form of artistic expression is, ironically, essentially a very organic one. It creates an illusion of extended reality: blurring the boundaries between the real and the represented, it lets the viewer directly into the intimate space between the photographer and his model. Even assuming the obvious possibility of gradation and the resulting potential abstract nature of pictures, photography is still the closest to the actuality any form of art can get. Even if the composition you observe is not spontaneously captured but staged, therefore artificial, the emotions that radiate from it resonate with you because the people depicted look exactly like you and the objects they interact with look exactly like those you see every day. Experiencing photography requires significantly less visual imagination than any other art medium; you just take it all in as you go. This initial ease of author-audience interaction gives photographers an obvious upper hand: it leaves a big room for experimentation, viewers’ identification with the work being granted notwithstanding. They get to switch between genres, mingle the forms, and play with the limits of the verisimilitude, all avoiding reductive labels, as long as what they do can qualify as ‘photography’.

Take Barbara Brändli, for instance, whose solo exhibit Poética del gesto, política del documento (Spanish for Poetics of gesture, politics of the document) is one of the central shows of PHotoESPAÑA 2024. Although her work could be described as documentary photography, this would certainly be a limiting definition and one that wouldn’t do her justice. Yes, her pictures undoubtedly document, and thoroughly and beautifully so, the reality of certain social groups, but they do not stop there. Brändli was fully committed to her projects, which she perceived as wholes aimed not only at capturing the circumstances she found herself in but also at exploring the humanity present in them. For her, photography was a dialogue, an interaction between the photographer and the photographed. She wanted to give her subjects a voice: My thing in photography is the human gesture, the face, what people do, getting people to see something that perhaps anyone else in the same place would not see or feel, she said. It’s like having something that others can’t see. It’s hard to explain.

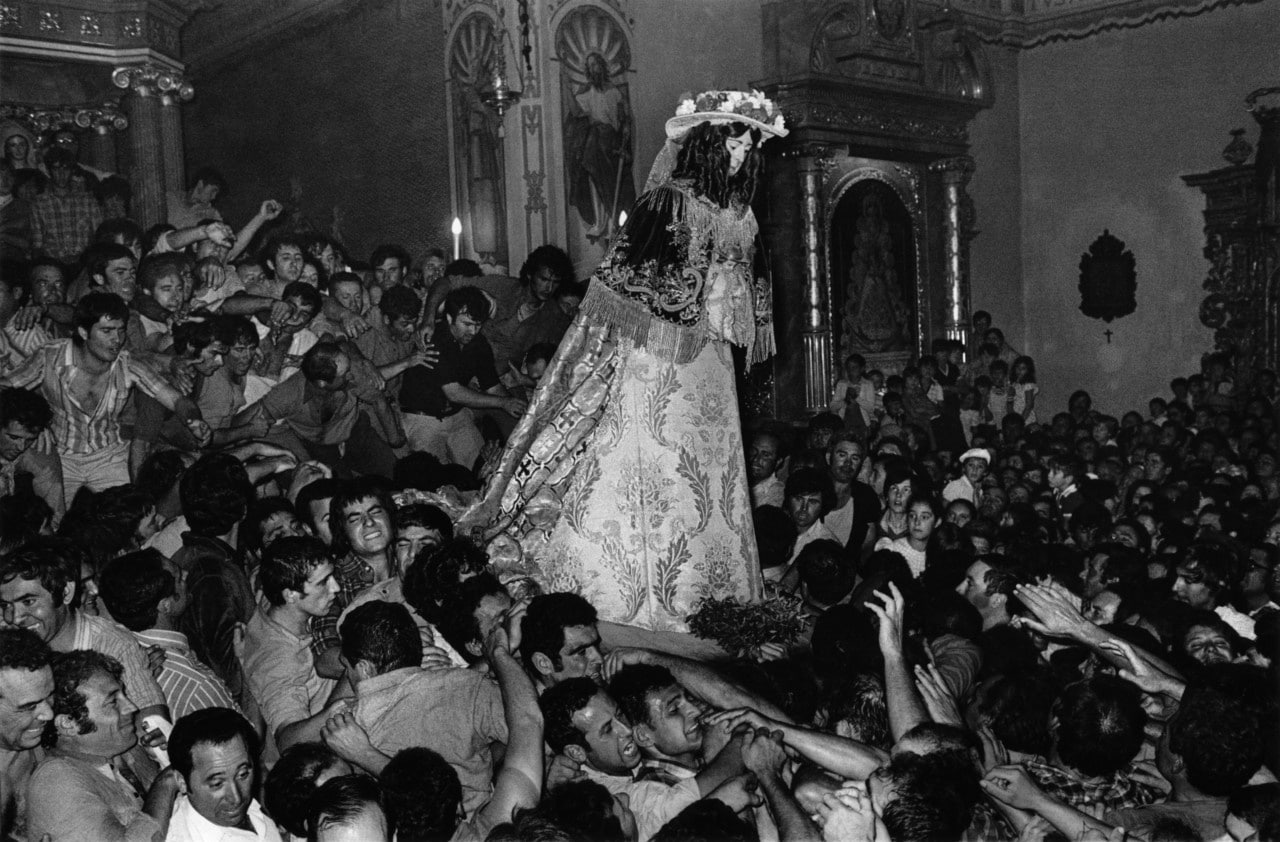

Cristina García Rodero The virgin returns to the temple. Almonte. Spain. 1977. © Cristina García Rodero | Magnum Photos

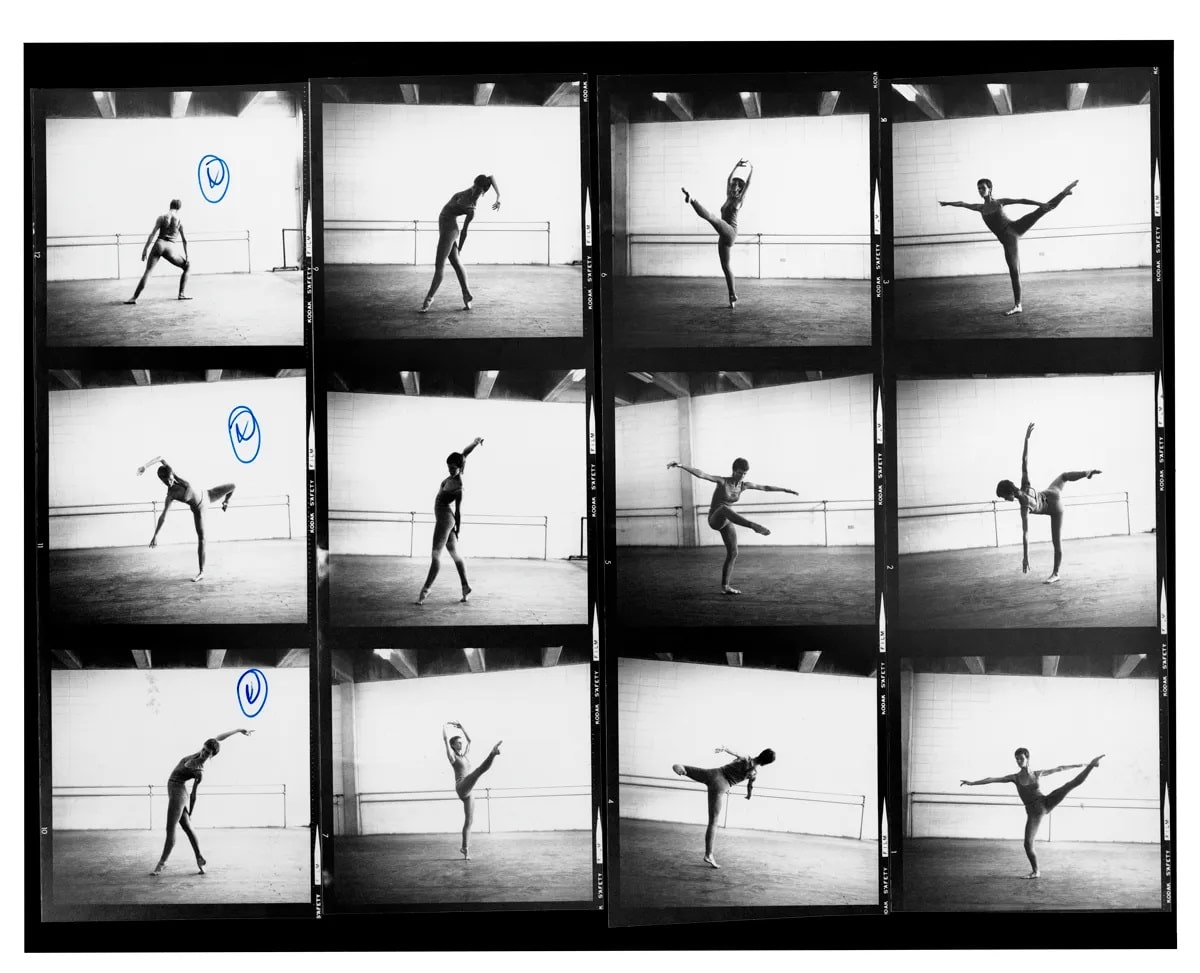

s/t. Fundación Danza Contemporánea, Caracas. 1962 © Barbara Brändli/Colección C&FE

Brändli’s photobooks, the most famous of which, Sistema Nervioso (1975), was included in Martin Parr’s selection of best photo publications (PHOTOBOOK PHENOMENON, 2017) and thus earned her international recognition, are unquestionably her most ambitious undertakings. Each being an intersection of the visual and the verbal, including fragments of interviews’ transcriptions, documentary fiction, or poetic aphorisms, they effectively prove the flexibility this medium is capable of: a photo mirrors the artist’s gaze; it has the power to bring out some hidden truth or beauty the latter sees and can’t express otherwise. It is never just documentation of reality – it is, in its essence, always a comment. With this intrinsic capacity of supple interaction with verbal discourse, photography becomes a tool for Brändli to explore a phenomenon she’s interested in and to provide the audience with a comprehensive, multifaceted study of it. It allows the artist to tell a story or take a stand in a story that’s already out there, all without actually positioning herself categorically. All in all, a very subtle yet efficient type of social commitment.

s/t. Fundación Danza Contemporánea, Caracas. 1962 © Barbara Brändli/Colección C&FE

And while Barbara Brändli’s legacy is definitely to be situated more on the photojournalistic side, it also cannot be classified as photojournalism per se. Her pictures are bravely explorative and magnetic; they radiate beauty that is both very pure and very human, and this desire to chase unspoken, metaphysical truths is, by definition, artistic. Nevertheless, for a photograph to operate as a means of personal expression, it doesn’t have to be intended for a creative purpose. Every photo, however internationally realistic and unbiased, presents a specific perspective, a crafted vision of things that follow directly the one manifesting itself in the author’s mind. It’s hardly an objective representation of reality, but it is a wonderfully interactive one. Exploiting its own natural power of visual captivation, it misleads the viewer with recognizable images to create a sense of empathy and identification that is particularly difficult to find in other forms of visual art.

Some people think the photograph is reality; they don’t realize that it’s just another form of depiction, David Hockney once said. España oculta (Spanish for Hidden Spain), another project organized in the aftermath of our unceasing, shared interest in photography, is a good example of that. The exhibition is an extension of Cristina García Rodero’s years-long initiative consisting in traveling around Spain and documenting the most bizarre, forgotten, and sometimes slowly dying local habits and traditions. Engaging with those pictures is part of a strange yet exceptional, two-level experience. First, the subject matter itself is truly uncanny: Rodero’s research, anthropological by motivation, had led her to discover and depict rituals so extraordinary it may be a good thing they are hidden after all; left untouched in places where no one can jeopardize them. But then, there’s the actual photos: so genuine, but also dark and mysterious, they add a special depth to the depiction. The artist’s evident effort to maintain visual integrity and a consistent, black-and-white color palette throughout all the individual shots causes them to interact with one another, each constituting a chapter in the story she wanted to tell. Somewhere between the real world and Rodero’s take on it, an unnamed shift is taking place. It invites the viewer in, really makes him want to believe what he sees, but doesn’t pretend to push him into total oblivion. Nonviolent but suggestive, and yet again, very efficient.

So when one goes through programs of photo festivals every year, all so extensive and varied, when one attends countless exhibits and catches the honestly intrigued look in the eyes of so many other visitants, it becomes clear that what modern-day photography tries to do (and achieves) is to actively partake in social reality and its underlying discourse. Whether consciously or not, photographers use the power of visual empathy to impregnate the viewer with a message, which the latter takes home with him unknowingly, sufficiently stimulated by the sole fact of attendance. They always leave us with just thought, an idea that is not even being verbally uttered, not to mention forced upon the audience. It’s a mere suggestion, a subtle tickling of the senses – the conclusions are to be drawn individually. And they will indeed be drawn, because at some point it is hard to say whether what we saw is a freeze frame of a real scene or an artificial recreation of one, and frankly, it does not actually matter. In the end, the faces we are looking at look like ours, and the world their owners live in we share. Photography offers strange perspectives on something deeply familiar; it tells us stories we didn’t know existed, didn’t know where to find, or didn’t want to hear.

That is probably why photo festivals are so universally liked: they are like a coffee date with a childhood friend. A seemingly new, unfamiliar conversation with a person you know nothing about, and yet one you feel really comfortable around and connected to on a deeper level. That, and a certain indulgence in imaginative laziness. Plus the free tickets.

https://phe.es/exposicion/barbara-brandli/

https://www.circulobellasartes.com/exposiciones/cristina-garcia-rodero-espana-oculta/