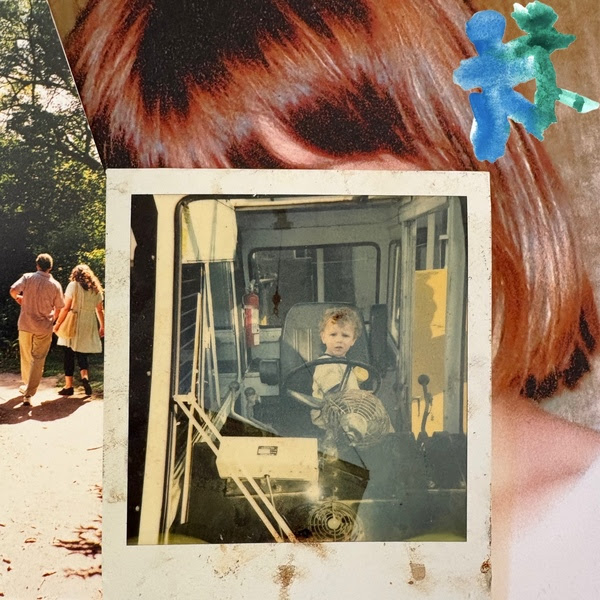

Photo credit: Christopher Noxon

On February 27, Eliza Noxon will release her debut full-length album Good Monsters With Bad Habits. Today, she offers its first and most arresting glimpse with “You,” a stark, emotionally charged introduction that traces the raw contours of grief with unflinching clarity. Built on spacious guitars and a steadily intensifying vocal performance, the track feels both intimate and seismic — a quiet scream that lingers long after it ends.

Written in May 2021, in what Noxon describes as a dark, chilly dorm room, “You” emerged more than a year after the death of her brother, at a time when grief still felt all-consuming. The song captures the isolating loop of loss: seeing someone everywhere, wishing time could be undone, feeling separated from the world while standing inside it. Unlike earlier expressions of her sorrow, this track leans into anger and rage — simple in construction, but devastating in its honesty.

“I found a way to scream and kick,” Noxon explains, channeling fear, fury, and absence into something connective rather than consuming. That catharsis deepened in the studio, where Jake Reed’s driving drums and Pierre de Reeder’s masterful production allowed the song to fully open up. Listening now, Noxon describes the track as a collective release — a space where anyone who has lost their person can feel seen.

Musically, “You” sits at the intersection of folk intimacy and indie-rock tension, a hallmark of Noxon’s songwriting. Her work favors emotional clarity over polish, pairing open tunings with expansive arrangements that leave room for vulnerability to breathe. The result is music that feels deeply human — searching, grounded, and unafraid to sit with discomfort.

That sensibility runs throughout Good Monsters With Bad Habits, an album that began as an exploration of early adulthood — leaving home, graduating high school, stepping into uncertainty — before transforming into something far more essential. After her brother’s death in 2019, the record became a lifeline. “Writing these songs saved my life,” Noxon shares. What remains is a vivid portrait of survival, fractured identity, enduring love, and the long shadow grief casts over growing up.

Noxon’s journey as an artist has been quietly unfolding for years. She released her first single, “Hummingbird,” at just twelve years old — later featured on Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black and now surpassing eight million streams. Her 2017 EP Save Your Breath laid the groundwork for what would become her most personal work yet. Produced by Pierre de Reeder (Rilo Kiley), Good Monsters With Bad Habits marks a turning point, solidifying a voice that has been forming patiently and purposefully.

Her influences — Big Thief, Typhoon, Pinegrove, and Feist — echo in her balance of restraint and emotional weight, but Noxon’s perspective remains unmistakably her own. Beyond music, her life has been shaped by movement and curiosity: earning degrees in Education and Interdisciplinary Artistic Studies from Brown University, assisting puppeteers in New York, teaching kids to milk cows in Vermont, and spending a year aboard a Caribbean schooner teaching sailing and sea shanties to underprivileged youth.

With “You,” Eliza Noxon doesn’t offer easy answers — she offers truth. It’s a song that sits with the ache, honors the absence, and reaches outward, reminding listeners that survival, however messy, is still an act of connection.

“You” is out now on Bandcamp and all digital platforms. The official video is available on YouTube.

Good Monsters With Bad Habits arrives February 27.

“You” feels like a scream whispered into the void, raw, unfiltered, and quietly devastating. What did it take emotionally to revisit that version of yourself in the studio, and did the song change your relationship with grief?

Writing “You” brought out a lot of deeply held feelings and beliefs I didn’t know were buried inside me. It felt like opening one of those cans of expanding snakes disguised as nuts; suddenly all this anger, hopelessness, and resignation came pouring out. Even though it was painful to write, it was a cathartic kind of pain.

At the time, I was a college student living with roommates, trying to pass my classes, join clubs, and have a life. Inside, though, all I could think about was my brother. I didn’t feel like I could grieve him openly (talk about bringing down a room), so my music became my only escape. Putting those feelings into words and melody helped me process them; it made me feel less alone and less lost.

By the time I was in the studio recording the song, I had come a long way in healing. In a strange way, it felt good to return to that time—to remember how lost I had been and how much my life had changed since. But there was also a sick part of me that missed feeling that sad, as if the more I healed from the grief, the more I lost him all over again.

So yes, it’s complicated. Mostly, though, the song feels like a point of connection—a raw nerve I’m extending out into the world, in the hope that it might help all of us feel a little less alone while processing loss.

You’ve said writing these songs “saved your life.”At what moment did the album shift from a coming-of-age project into a lifeline, and how did that transformation reshape the entire record?

I began writing this record in high school, just after releasing my first EP, Save Your Breath, in 2017. I’d always been enamored with the idea of writing a capital-R Record. To me, a record is to a songwriter what a novel is to an author: a format that allows space for complex, expansive themes and sonic ideas.

When I started writing, I imagined this project as a big coming-of-age story—graduating high school, moving away, entering the world. The first song on the record, “birthday song,” was written on (get this) my seventeenth birthday. Listening to it now, I feel a bit bitter about my hopeful optimism, my vision of a world that seemed glittering and ready to welcome me with open arms.

When my brother died on New Year’s Eve, 2019, everything about my process changed. I stopped thinking about writing a record, telling a story, or making a product. Instead, I wrote the music I needed to hear: raw, lonely, expansive. I say those songs saved my life because they allowed me to speak the depths of my grief out loud and invite others to share in it.

The result is a record that still functions as a coming-of-age story—just with a big, jagged hole right in the middle. The final song on the record, “One More Round,” was written on my 21st birthday, and I love the way it echoes many of the same questions and themes I was grappling with at seventeen. I’m incredibly proud of how these songs speak to one another and form a cohesive narrative. When the album comes out in February, I recommend listening from the top, in order.

The interplay between spacious guitars and intimate storytelling gives Good Monsters with Bad Habits a feeling of breath, expansion and contraction. How intentional was that tension between sonic openness and emotional heaviness?

Yeah, thanks for pointing that out—it’s something I really love about these songs, and I think it comes directly from my writing process. I wrote most of them in open D and open C tunings on guitar. I’m mostly self-taught on string instruments, and I play in a pretty unconventional way. I’m not left-handed in most parts of my life, but when I taught myself ukulele—and later guitar—I picked them up upside down and backward. As a result, I now play right-handed string instruments left-handed.

Paired with open tunings, this approach creates a really distinct voicing and allows me to explore in a playful, unstructured way. I don’t think about my songs in terms of chords—I honestly couldn’t tell you what key most of them are in. Instead, I remember them by the shapes my hands make and where those shapes live on the fretboard. When I’m writing, I’m thinking less about harmony and more about dynamics: where a song begins, and where it wants to go.

Music can convey emotion in a way nothing else can, because it breathes and moves through the body much like a feeling does. When I’m writing, I’m trying to mirror that—tracking patterns of breath, and the way emotions move through me.

Your brother’s presence is woven into the album like a quiet pulse. How did you navigate the line between honoring personal memory and creating something universal for anyone who’s ever lost “their person”?

I wasn’t really trying to make something universal when I was writing. I was writing about how I felt—how I was processing, how I was moving through it. I was even a little shy about writing directly about my brother, and if you look closely, there’s actually very little detail about him in these songs. He’s there, of course, but only ever in relation to me.

This isn’t a work that tries to keep him alive or capture some essential version of who he was. I know I could never do that in a real way. Besides, while he was alive, he was a much better writer than I’ll ever be, and he captured his own essence through his work.

This record is about me processing my grief—about keeping some part of our relationship alive, about calling out to him the things I wish I could say, and wish I had said while I had the chance. I’m honored that so many people who’ve listened to these songs have connected with them and found their own missing person hidden inside. This isn’t an album for the people who died; it’s for the ones who are still here.

You’ve been releasing music since the age of twelve, your song “Hummingbird” even appeared on Orange Is the New Black. How does young Eliza, the one who wrote that first single, show up in this debut album?

I think that young Eliza exists in all the songs I write. Even as my practice and skills have evolved, my music always has some essence that feels uniquely me. I know that little twelve year old writing songs on her ukulele would be incredibly proud of the work I’ve done to make this debut happen.

Working with Pierre de Reeder, which for many indie fans is a dream collaboration, adds another layer to the story. What did his production unlock in you that you couldn’t have accessed alone?

Yeah—that’s something twelve-year-old me would definitely be freaking out about. I’ve always loved Rilo Kiley and had so much respect for Pierre as an artist, so getting to work together felt like a dream come true. We recorded the entire record, plus a few extra tracks, over the course of about a week while I was home on winter break. It was a mad flurry of sonic connection between me, Pierre, and an incredible group of studio musicians, including Jake Reed on drums, Sean Hurley on bass, and Phil Krohengold on keys, lead guitar, and twiddling magic knobs. It honestly felt like something out of a movie—I was so lucky to be working with them and learning from their combined depth of experience in the music industry.

I think Pierre found things in the record that I didn’t even know were there. I’m not very production-minded, especially while I’m writing and working out songs, but I usually have a loose sense of what I want each track to feel like. Pierre took my rambling notes, inspiration playlists, and shoddy demos and turned them into something magical. He understood the dynamics of the songs in the same way I did and was incredibly open to play and experimentation.

You’ve lived a wildly eclectic life: puppeteer’s assistant, farm teacher, schooner crew member in the Caribbean. How have these seemingly unconventional chapters shaped the way you write about identity and growing up?

Oh man, those experiences influence everything I do now. When I graduated from Brown University in December of 2023, I had very little idea what I wanted to do. I held two degrees—one in education and one I designed myself called Interdisciplinary Artistic Studies. I wanted to explore, to teach, to be in the arts, to find a creative community. I basically wanted to live everywhere and do everything.

That eagerness—that curiosity—is also the energy that drives me to create. I love writing music, but I can’t do it without things to write about. Being an outdoor educator—whether on a farm in Vermont or in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean—has pushed me to learn so much more about myself, the world, and how we all fit into the bigger picture. I know my songs are better for it, and I’m excited to start sharing some of the newer work I’ve written soon.

Your influences, Big Thief, Feist, Typhoon, tend to build worlds where vulnerability feels radical. What emotional or artistic risks did you take on this record that scared you the most?

I mean, a lot of these songs are really vulnerable. Sometimes I do feel a little uncomfortable playing them in public, because it can feel like I’m dropping a huge weight right into the middle of the room. But I’m inspired by artists I love—like the ones you mentioned—who are able to hold so much feeling in their work and invite others into it without making it feel overwhelming.

Over time, I’ve learned that sharing my story, even when it’s hard to carry or hard to hear, is worth the fear.

The album’s title, Good Monsters with Bad Habits, carries a beautiful contradiction. Who are the “monsters” in your world, and what were the “bad habits” you had to break, or embrace, to finish this album?

The title comes from a book my dad and brother made together when my brother was really little. Before bed, instead of reading picture books, my brother would describe creatures to my dad, and together they would write the stories of the monsters while my dad drew their portraits. My brother loved giving the monsters strange quirks—eating endless piles of junk food, being harsh with their children, or constantly losing their belongings. He always made a point of clarifying that these flaws didn’t make any of the creatures bad. He would say they were all good monsters with bad habits.

That phrase stuck with me, becoming part of our family mythology. As my brother and I got older, we were inseparable—best friends and creative partners. We both felt a little like monsters ourselves: a bit too loud, too brash, too goofy. But together, we were good, balancing each other out.

When he died, it felt like the invisible wall I’d been leaning against suddenly disappeared. I had to learn a lot about how to be a human being in the world. I had to forgive myself for many of my bad habits, even when I couldn’t fully convince myself that I wasn’t a monster.

To finish this album, I had to come to terms with my own bad habits—being too hard on myself, second-guessing my feelings, and sometimes wanting to look away from the mess. Learning which of those habits to release, and which to hold with compassion, became part of the process.

I think we’re all monsters in that way. We all have bad habits, we all wish we were kinder to ourselves and the people we love, and we all fall short. But the act of trying to be better—that ongoing effort—is what makes us good monsters.

As you prepare to release your debut album into the world, what do you hope listeners carry with them after sitting with this record from beginning to end? Is there a specific feeling, scene, or truth you want echoing in their bodies?

I hope this music reaches people who feel seen by it. I know my answers here might make it sound like a brutally painful, sad slog—but it’s not, I promise. Every song offers something a little different, and I hope each one finds the person it’s meant to matter to most. Taken as a whole, I hope the record leaves people feeling hopeful and connected.

None of us are alone. All of us are searching for meaning, all of us carry pain, all of us are grieving in some way. So let’s do it together.