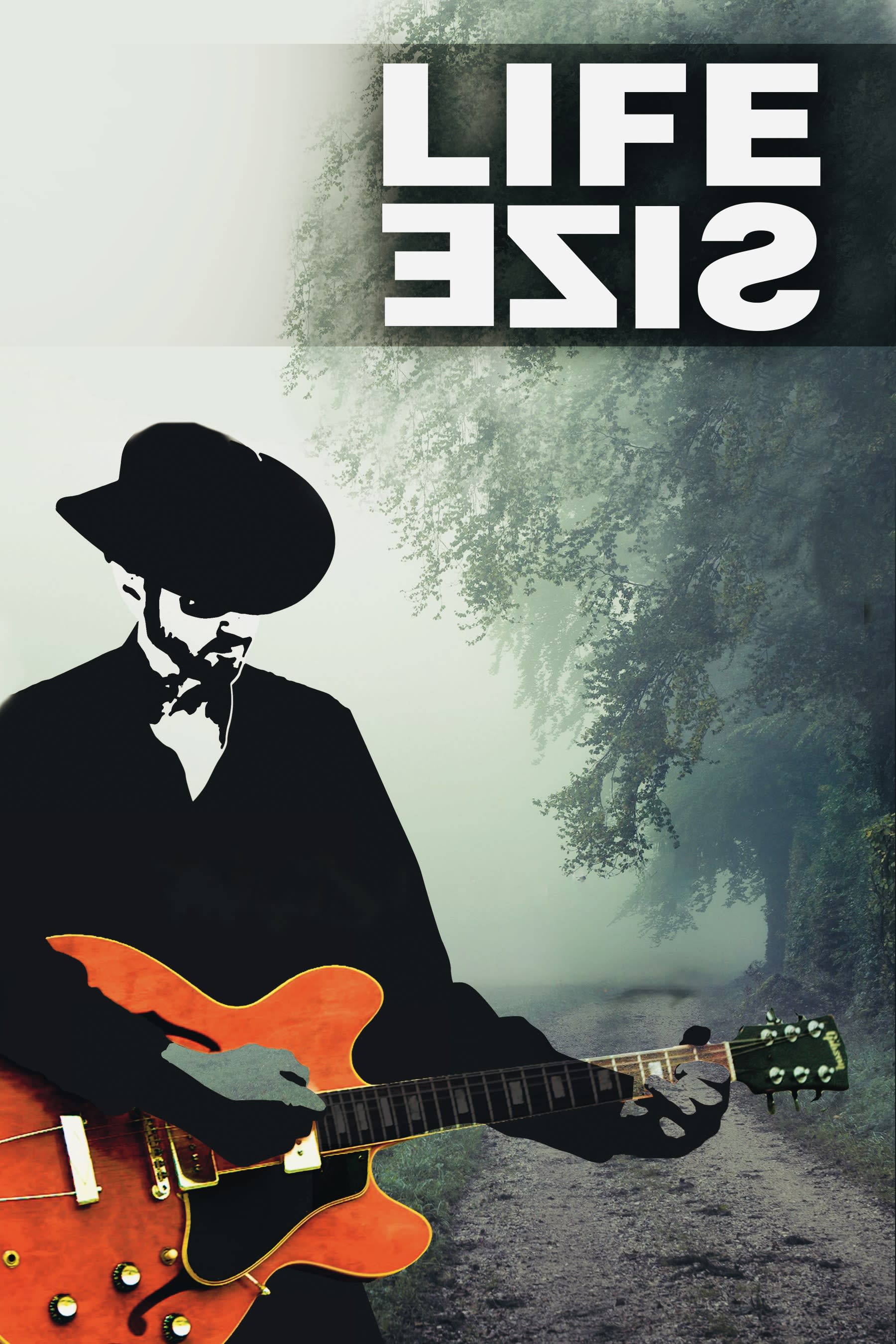

Los Angeles-based artist Scott Marshall returns as LifeSize with a stunning new record that bridges loss, healing, and creative rebirth. Produced by Grammy Award-winner Dave Darling (Def Leppard, Janiva Magness, Brian Setzer), with additional production and mixing by Scott Marshall himself and Ryan Lipman, the album is an expansive and deeply human journey through sound — equal parts cinematic and soulful.

Featuring an all-star lineup that includes Janiva Magness on lead vocals for the soul-stirring track “Always,” along with acclaimed musicians Arlan Schierbaum, Carl Sealove, Elizabeth Wight, Jeff Turmes, and Roger Carter, LifeSize feels like both a personal diary and a universal prayer.

Much of the record was written on Marshall’s 1966 Gibson 330 — the only guitar he salvaged from the devastating Woolsey fire. That instrument, scarred but still standing, became the spiritual center of the project.

“Every time I looked at it, touched it and played it, it was visceral,” Marshall reflects. “As if the guitar embodied the whole of my experiences and I had to somehow make it speak to get its stories out.”

That process of transformation is woven through every note of LifeSize. Blending alternative, roots-rock, pop, and cinematic storytelling, the album channels influences from Mark Lanegan, Nick Cave, The National, and Daniel Lanois, while remaining unmistakably Marshall’s own. His voice—intimate yet widescreen—guides listeners through tales of survival (“Buried Alive”), lust and longing (“Black Car”), spiritual reflection (“Man of Tao”), and fatherhood (“Where Does the Light Go?”), each track balancing poetic depth with raw emotion.

Highlights include the aching single “California Home,” a love letter to the Golden State; the haunting groove of “Cobra & Mongoose,” and the sweeping closer “Constellations,” which distills the album’s cosmic themes of connection and transcendence.

LifeSize has already earned acclaim from tastemakers and radio stations alike — with airplay on KCSN, KEXP, and The Krush, and praise from The SoCal Sound’s Mimi Chen, KRSH’s Bill Bowker, and MediaNews Group’s Jim Harrington, who hailed the music as:

“Impressive on so many different levels… a collection of vastly appealing roots-rock tunes that should appeal to fans of Mark Knopfler, Tom Petty, and Bruce Springsteen.”

For Marshall, LifeSize is not just an album — it’s an act of reclamation. A reminder that creation can rise from destruction, and that memory and melody can rebuild what was lost.

With this release, LifeSize isn’t simply revisiting the past — it’s redefining it, offering a record that feels both timeless and timely.

LifeSize is the project of Los Angeles-based artist Scott Marshall, blending heartfelt songwriting with roots-rock energy. His music has been praised by The Mercury News as “poignant” and “vastly appealing,” drawing comparisons to icons like Tom Petty, Mark Knopfler, and Bruce Springsteen.

Growing up in Seattle during its cultural boom, Marshall absorbed a wide range of influences—from The Beatles and Hendrix to Sonic Youth and Screaming Trees—which continue to inform his expansive pop-rock sound. After relocating to California, he began releasing music under the LifeSize moniker with producer Dave Darling, earning national airplay and critical acclaim across three albums.

His breakout project, Woolsey, served both as a love letter to California and a fundraiser for wildfire recovery, with proceeds benefiting Direct Relief.

Now, with LifeSize, Scott Marshall continues to craft songs that are timeless, cinematic, and deeply human—music that doesn’t just tell stories, but helps you feel them.

Your new 24-track double album captures a wide spectrum of human experience — love, loss, survival, redemption. How did you decide which emotional themes were essential for this project, and which ones you’d leave out?

Writing is not a natural or prolific process for me. It requires a lot of work. Sometimes I will be inspired and a whole song, chorus or verse will come to me. But usually, it’s just a bit of lyrics or music. I have hundreds of fragments in my computer. When I have time to write, I go to my computer and see if anything moves me. If it does, I will work though recording a demo.

But it’s rare that I sit down to intentionally write a song about a certain subject. There are a couple songs where I wanted to write specifically about loss, politics, or love, etc. But normally it’s the lyric idea or the mood of the music that dictates the subject matter for me. I did try to make the album as thematically varied as possible. I didn’t consciously attempt to leave out any specific themes.

You wrote much of the album on your 1966 Gibson 330 — the very guitar you salvaged from the Woolsey fire. How did that instrument become a character in the record — and what did that physical connection give you as a writer?

Many of the demos for this album were especially difficult. Every time I looked at my 330, touched it, played it, embraced it, it was visceral, as if the guitar embodied the whole of my experiences and I had to somehow make it speak to get its stories out. And it is one of the very few physical objects that I have as connective tissue to a life before the fire.

The production involvement of Grammy-winner Dave Darling seems to elevate the sound into cinematic territory. What was the dynamic like in the studio — and how did you balance his input with your own artistic vision?

Dave is very busy, and even though he is a close friend, I had to be persistent (laughs). We have a pretty relaxed dynamic in the studio. I think one of the things that is appealing for Dave doing a project with me, is that it’s as much about hanging out with a friend as it is about the music. When I first approached him, I was quite insecure actually, because Dave is a force of nature when it comes to singing, songwriting, playing instruments, and producing. He is a master musician. There is a very deep vulnerability in playing somebody a song I have written, especially a friend that I admire so much as an artist. Luckily, we had been playing in a band together for a short period, and I started to bring in some songs and play them for the band. So, some of the songs Dave had heard already. When I called him up, I was surprised that he said “yeah man, let’s get together and listen to the demos, I know what you do.” I feel privileged that Dave liked the demos and wanted to produce LifeSize. Honestly, he was less forceful than I expected. I think he just treated me like one of his other artists, expecting me to drive, or at least help drive the project. I think because we are friends, we were able to bring that friendship, love but no BS, short hand experience to the album.

We did almost everything in his home studio. We started by importing all my demo tracks into his software. Some instrument and most vocal tracks were re-recorded, but some of the demo tracks are in the final album mixes. I begged him to sing vocals on several tracks, and actually envisioned the project to have many more vocalist on it than it does. I didn’t feel like my voice fit some of the music I had written. I felt like I was right for a few songs, but not the majority of them. Dave was very good about making me feel safe and comfortable in the studio. And he also encouraged me to try to do vocals for most of the songs. I remember, one of the many things he said to me that really helped was, “you’re never going to be technically the best vocalist. But you have something that’s more important, believability, you are connected to the songs because you wrote them, and your voice, and the way you sing them and tell the story is honest. And people will relate to that more than technical perfection.” The majority of instruments are played by Dave and I, but Dave was able to get a lot of other fantastic musicians that he knew to also contribute, kind of his core working crew for other albums.

You blend alternative, roots-rock, pop, cinematic storytelling, nodding to artists such as Mark Lanegan, Nick Cave and The National. How do you navigate influence vs originality, particularly on a project this expansive?

I am a lifelong music lover. I enjoy so many different artists, and genres of music. But I try to be realistic about what I can do as an artist. I’m not gonna play the guitar like Jimi Hendrix or write and perform songs like The Beatles. My favorite singer songwriter since the late 1980s is Mark Lanegan. Being exposed to artists like Mark, Pixies, Tim Harden, Lou Reed, Magnetic Fields, J.J. Cale, Lambchop, The National and so many others, gave me the confidence to realize that I had my own unique sound and sensibility to offer.

Even if I tried to sit down and write a Neil Young song, it would never come out that way, because it’s getting filtered through me. Neil has said that he often took partial melodies or chord structures from other artists to inspire him to create his own work. Most of my songs start with chord structure ideas, or partial melodies that I have in my head. Often, musical ideas I have in my head are much more complex than what I can actually get into a song. I do not consider myself a natural musician. As a matter of fact, I don’t really consider myself a musician. I consider myself a singer-songwriter and an artist, but not a musician.

So, creating a song for me is kind of like speaking a second language that I’m not completely fluent in. I have ideas, and I can hear them in my head, but they have to go through a translation when I’m creating a demo. So sometimes they come out simpler or more complicated or very different than what I originally heard. I rarely try to write in the voice of another artist, but sometimes I do. An example is “Your Love is so Hard to Find”. With that song, I was trying to do something that felt like J.J. Cale.

Some critics have compared my work to Tom Petty, Mark Knopfler, Springsteen and others. I think that’s because I’m able to create songs that are mood and vibe oriented, but also songs that have more of a pop or rock feel to them.

One of the songs, “Where Does the Light Go?”, apparently touches on fatherhood. In what ways did your personal life and relationships shift the way you approached writing and performing this time around?

Yes, Where Does the Light Go? is a purposely quirky pop celebration of fatherhood. Taking inspiration from the Talking Heads album Little Creatures, I tried to relay my experiences of lying next to my kids at night while gently coaxing them to fall asleep. However, I was also conscious and curious enough to know I needed to allow that special, suspended space between falling asleep and sleep, for all the cosmic, creative questions of a child that can, and cannot be answered.

My personal life and relationships have always inspired and influenced my writing. But being a father has enrichened and expanded my idea of love and relationships, and what it means to treasure and be a steward of those close to me and the planet as a whole.

The album moves from intense heartbreak (“Buried Alive”) through spiritual awakening (“Man of Tao”) to cosmic transcendence (“Constellations”). Was there a conceptual arc you set out to follow — or did the structure emerge organically?

I think of this album as a collection of short stories. It’s not a novel, but it does have a literary cohesiveness to it. I’ve always liked albums with broad subject matter and musical variance, and I tried to have that on LifeSize. The songs selected, and the track order was consciously created in an attempt to give the listener an expansive and variant cinematic experience.

In your press release you say you hope listeners “find compassion and solace” in your music. What role does songwriting play for you — healing, catharsis, connection — and how do you hope it functions for the listener?

Yes, healing, catharsis and connection are great words to describe some of the roles that songwriting plays for me. I think art is one of the most mystical and necessary human creations. There is an invisible fabric that exists between humanity and divinity, and I think art makes that intangible thing visible. And music in particular, at least for me, is the most transcendent of all the arts.

For me, creating is a lot of very hard work, but in the process of it there is always discovery, joy, therapy, and release. There is a satisfaction and benefit to just the creation itself. But of course, most artists also want to communicate, and that’s what I’m trying to do with this album, hopefully create relatable connections with listeners, so they know they are not alone.

Given your previous album was a tribute connected to California wildfires, and this new one is even more expansive, how do you view the evolution of your artistry from that turning point to now?

At this point in my life, I’m a bit more reflective and appreciative in ways that I had not been able to obtain before. And I hope that comes out in my art.

You’ve worked with an “all-star lineup” of collaborators — from Janiva Magness to Jeff Turmes and more. How did collaboration shape the finer textures of the album, and where did you decide to keep things deeply personal and solo?

That’s a great question. I touched on this a little already, but in the beginning of creating LifeSize I never wanted it to be a “solo” project. I always envisioned that I could hopefully attract other writers, especially my producer Dave Darling, to be an active part of LifeSize. And I always saw the songs being sung by multiple vocalists, a bit like Zero 7 or the Alan Parsons Project. But Dave encouraged me to attempt the vocals and make LifeSize my own.

Dave has worked with so many incredible artists and musicians, that he was able to pull in people that he felt would contribute something unique to each song. Initially, for the song Always, we had thought about using Elizabeth Wight for it, because we had already recorded Back of a Car with her, and she did such a fantastic job and was amazing to work with. But Dave happened to be producing an album with Janiva Magness at the time, and I mentioned I thought she would be great for it. Dave was like, “OK I’ll play it for her”, but I never expected that she would accept. I think Janiva is one of the greatest female vocalists of all time, so I was absolutely thrilled when she said OK.

With so many tracks in one collection, how do you recommend your audience engage with the album? Do you see it as one cohesive journey to experience front-to-back, or a collection of stand-alone pieces to dip into?

Well, I’m “old-school” when it comes to the album experience. So yes, I very much would like the listener to be able to take in the work all the way through as a single piece, because that is the way I arranged it and intended it to be listened to. But I think the album would also work if it was on shuffle, or if listeners listen to one track or a couple tracks at a time. It also works on that level.

I did do a limited double album vinyl pressing, so if listeners want to get a true “old-school” album experience where they can hold the physical artifact, while looking at the art work, lyric sheets, etc., that is available.

Visit LifeSize website HERE: https://www.lifesizemusic.net/