© Gregory Copitet.

To actually know the city one lives in is to be able to determine its one distinguishable characteristic. This one specific element that underlies, if not guarantees, the city’s social functioning and substantially contributes to perpetuating what has come to be called its “energy.” In Paris, few would argue that this trait is the city’s artistic scene. Mature, vast, and incredibly heterogenic, it stands out not only as Paris’s inherent quality but also as the main trigger of the constitution of the Parisian myth. Like that, for the last century or so, the French capital has been the chosen home of all the wandering artists, the place to be for the ambitious, success-hungry ones, and the perfect fertile ground for all kinds of new art tendencies and movements.

The proliferation and the coexistence of many different avant-gardes that happened to take place in Paris during the last 100 years of history have resulted in the consolidation of an art scene so strong and esteemed that to be included in it represents for many the ultimate goal and the supreme distinction. This heritage, maintained till this day in both universal recognition and physical multiplication of institutions, festivals, and galleries, has led to the creation of a milieu so perfectly inviting that, when it comes to the potentiality of making things happen, the limits of one’s creative capacities are quite literally synonymous with one’s possibilities.

© Gregory Copitet.

Following this very logic, I came to discover christian berst | art brut gallery, the existence of which is the ideal illustration of what the previous two paragraphs tried to explain. The gallery, small but strategically located in the hip and artistically renowned district of Le Marais, was founded almost 20 years ago by Christian Berst, then literary editor and publisher.

As the name implies, the gallery’s focus is art brut, the term coined in the mid-20th century by the painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet. While it is true that the label has its English equivalent, outsider art, and a quite long-standing, parallel tradition of its own in both the UK and the US, it’s of course no coincidence that the interest for this kind of creative activity first originated in France: it’s the country’s, or more specifically its capital city’s, everlasting artistic curiosity and fervent enthusiasm for the mise en œuvre of every sparking idea that allowed for it. For art brut (literally “raw art” or “rough art”) is, in simple terms, all art created without the viewer in mind, that is to say, exempt from any desire whatsoever to respond to or even satisfy the feelings or expectations of the public. “Those are really works that are reflexive and self-centered by definition,” Christian Berst tells me when asked to define art brut’s specificity, “it’s about creating a habitable world for someone for whom the world as it is is not enough, whether it’s because of a mental otherness or a social one.”

untitled, 2015. single print digital color photography, exposure on Fuji glossy paper, 38 x 27.4 cm

Indeed, the first investigators and theoreticians of art brut were really drawn into the exploration of the relation between mental illness and creativity, as the junction of those two represented from them a purest form of artistic expression. And while the defined medical condition is not a criterion per se for an artist to be included among “outsiders,” the presence of deep emotional trauma is often the essential component of this categorization. In the end, it’s this trauma that successfully keeps those artists on the verge of society, in a permanent impossibility of responding to the predefined norms of the social canon. The work of art brut artists is, as Christian Berst put it, “the oeuvre of utmost and total sincerity.” It’s art born from an authentic impulse, a true pursuit of creative output in the hope of finding solace. All in all, a very beautiful illustration of the human condition in one of its most natural aspects.

untitled, 2009. single print digital color photography, exposure on Fuji glossy paper, 38 x 28.8 cm

untitled, 2015. single print digital color photography, exposure on Fuji glossy paper, 37.8 x 27.5 cm

My coming across this not-so-hidden gem of the Parisian art scene merged with the simultaneous discovery of a rather hidden one, namely, the protagonist of their most recent exhibit: Tomasz Machciński (1942-2022). tomasz machciński: american dream. I made it all because of you, which was the title of the show that ended on November 10th, was centered around the relationship between the Polish photographer and the American actress Joan Tompkins and examined how the virtual presence of the latter in the first’s life had shaped his identity and constituted the base of his self-perception.

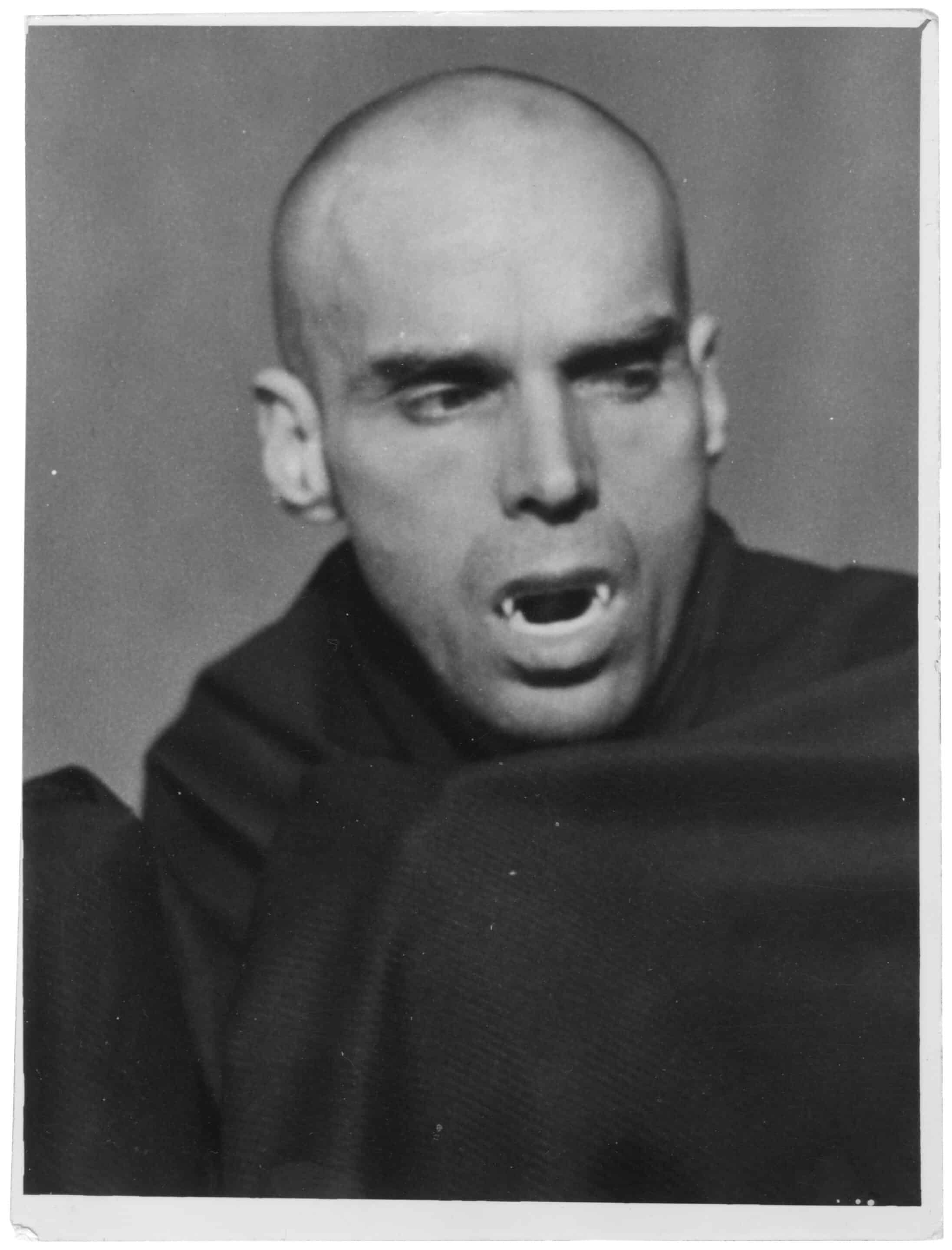

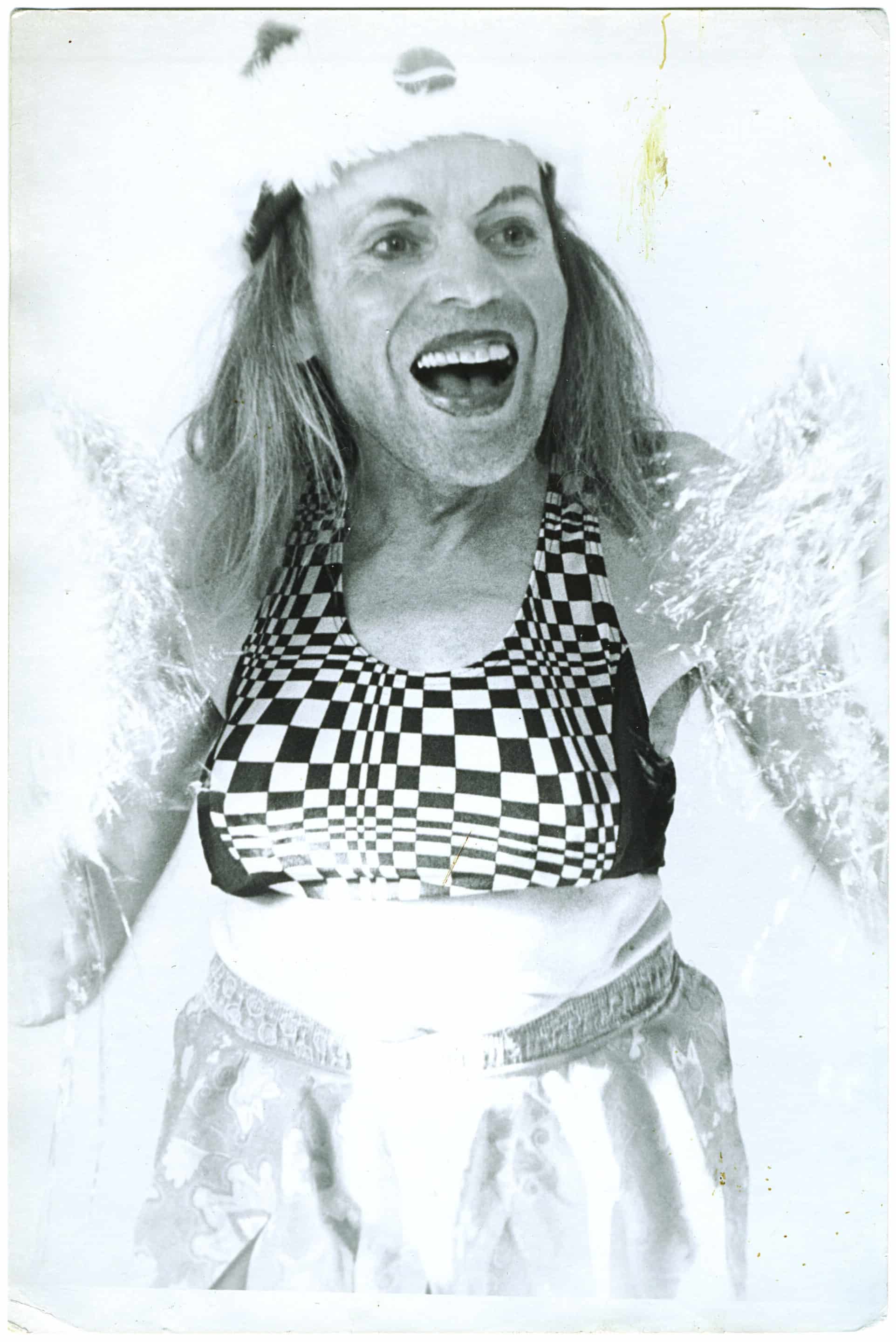

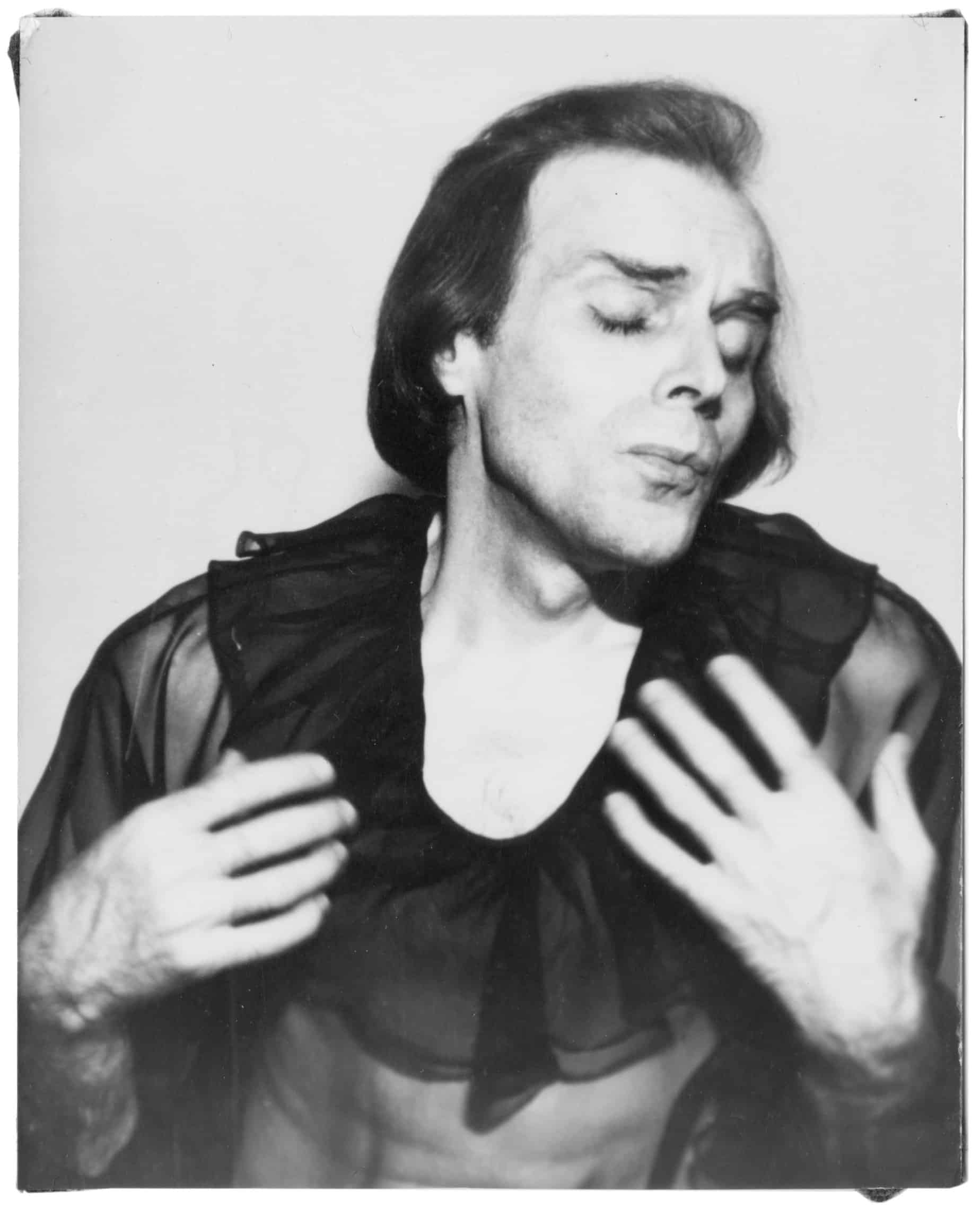

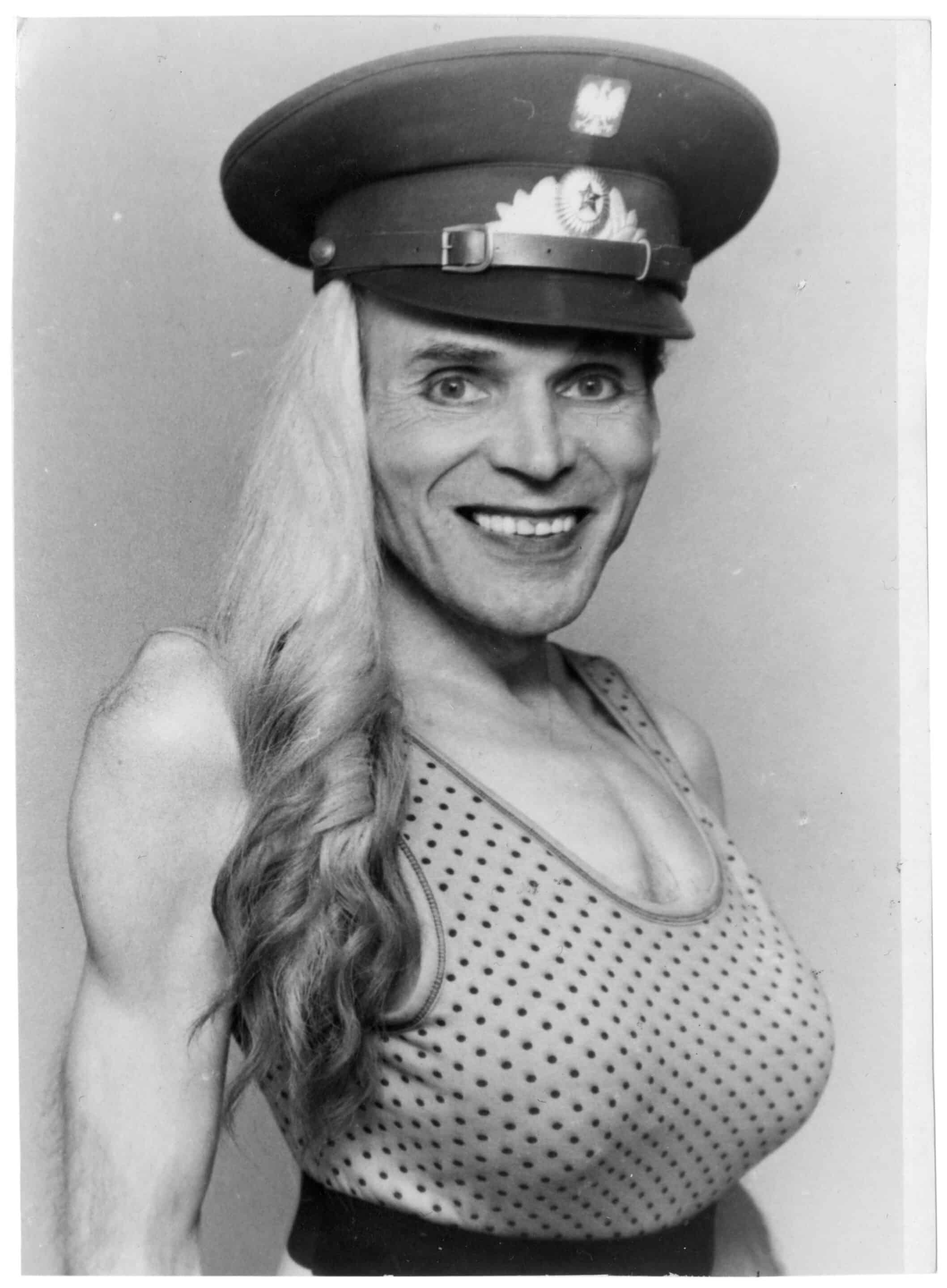

As it often goes with brut artists, Machciński’s biography is truly a remarkable one. War orphan, he was included in a support program of “remote adoption,” as part of which the Hollywood actress Joan Tompkins sent him her photo with an autograph and a note: “With love to Tommy from Mother Joan.” This gesture led little Tommy to believe that Tompkins was his actual mother, the assumption on which he based his definition of self and which he kept alive for the next 18 years, when he was finally brutally deprived of this illusion and confronted with the truth. Like that, the question of identity becomes central to his entire creation, and understandably so, as if this violent realization made him reconsider not only the way he positioned himself vis-à-vis society, but also the very limits of what one holds to be one’s identity. He started to dress up in very elaborate costumes, which he always put together by himself and from scratch, that each referenced but also defied a specific cliché, often coming directly from American culture. His legacy, consisting of 22,000 self-portrait photos, is a vast cross-section of characters from many ethnic, sexual, and social backgrounds, and the way the artist embodies them is evidently laced with irony, if not mockery.

untitled, 2016. single print digital color photography, exposure on Fuji glossy paper 37.8 x 29.2 cm

“What is particularly remarkable about him is an unquenchable need to expand his work and independence in his actions,” says Katarzyna Karwańska, one of the curators of the exhibit and the president of the Tomasz Machciński Foundation. “Machciński was not only a photographer but also a creator of costumes, a make-up artist, a set designer, a performer, and an archivist. He did not use wigs or any computer effects. He was the creator and the material of his art.” The artist’s consistency and dedication are a true “miracle of resilience,” to quote Christian Berst, who, immediately after meeting Machciński and discovering his work, decided to contribute to enhancing his international recognition. A mechanic by trade, the self-taught photographer spent most of his life unknown to the broader public, creating only to satisfy his own creative urge. It’s not until 2016 that he participated in the first important collective show in Warsaw called Po co wojny są na świecie? (Polish for Why are there wars in the world?). The exhibition turned out to be a pivotal point in his career, cementing his collaboration with Zofia Płoska-Czartoryska and Katarzyna Karwańska. The latter initiated the creation of the Tomasz Machciński Foundation in 2018, thus opening his way to various art events both in Poland and abroad (Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles or the Independent Art Fair in New York, among others).

untitled, c.1985. black and white silver photograph, single print on baryta paper, 13 x 9,8 cm

Christian Berst’s journey with Tomasz Machciński’s work, initiated by their encounter at Rencontres d’Arles and followed by the organization of a very successful solo show at Paris Photo 2021, concluded in the most recent exhibit, whose curatorship he entrusted to Karwańska and Płoska-Czartoryska. “We opted for the American thread to highlight a key aspect of his remarkable biography and creative path (the archival section tells the story of his correspondence “adoption” by American actress Joan Tompkins),” says Zofia when asked about the main idea behind the show, “as well as to show a coherent selection of photographs from all periods of his career. America was a constant presence in his work – from his first selfie as a Hollywood lover to his last color digital photographs, in which he played cowboys and cowgirls with a great deal of irony.”

untitled, 2005. black and white silver photograph, single print on baryta paper, 15 x 10 cm

In the end, the American motives, even though they’re just one of many thematic threads in his oeuvre, are essential to its understanding: they come back to the very personal and intimate quest of identity the artist embarked on when he first realized Joan Tompkins was not in fact his mother. “This multiplicity of identities that he takes on,” concludes Christian Berst, “is perhaps an unconscious response to the denial of identity he was confronted with when he was 18. Suddenly he was told, ‘This is not who you are’, while he built himself up thinking that he was precisely that. So he said to himself, ‘Very well, I’ll be everything else then’. It was a magnificent response, because at the same time it meant a miracle of resilience: he was someone who took his karma, which was, to put it mildly, not so terrific, and he created light from it. And that is extraordinary.”

untitled, 1987. black and white silver photograph, single print on baryta paper, 9.4 x 7.7 cm

And that’s probably what’s most striking about this artist: this ongoing, private pursuit that manifested in a series of truly impeccable, perfectly framed pictures, the subject matter of which seems to challenge established systemic norms and conventions. What others have done explicitly (Cindy Sherman, for instance, whose work is often compared to that of Machciński), he achieved absolutely intuitively, having not received art education or even so much as intended to depict anything other than his own introspective exploration. “We can look for affinities between his art and what was happening at that time in circles such as the New York avant-garde,” adds Płoska-Czartoryska, “but we should remember that Machciński created alone, without contacts with any artistic environment — neither in Poland nor abroad. These were his own explorations, set in the specific existential and cultural context of the socialist, Eastern European province. That is why his voice sounds clearly different from artists who looked at issues of mass culture from a Western perspective.”

untitled, 1997. black and white silver photograph, single print on baryta paper, 12.2 x 9 cm

But that is also why this comparison with “mainstream” art turns out to be particularly interesting: if Machciński, for the most part of his life, did not have any contact whatsoever with the artistic world, if he created out of the place of total genuineness and somehow still managed to achieve an effect canonical artists deliberately sought to attain, then maybe there is a question to be asked about what it all says about us humans. At the end of the day, maybe art really is the ultimate expression of our deepest passions and needs, and maybe all artists really try to do, regardless of their distance from the prototypical canon, is to try to find a way to embrace them.

Picture credits:

Color photos: Courtesy Tomasz Machciński Foundation and Christian Berst Art Brut

B&W photos: Courtesy Christian Berst Art Brut

Photo of Joan Tompkins, 1947: Courtesy Tomasz Machciński Foundation.

I would like to thank the members of the Tomasz Machciński Foundation, Zofia Płoska-Czartoryska and Katarzyna Karwańska, and Christian Berst, the founder of christian berst | art brut gallery, for their valuable input, which contributed significantly to the finalization of this article.