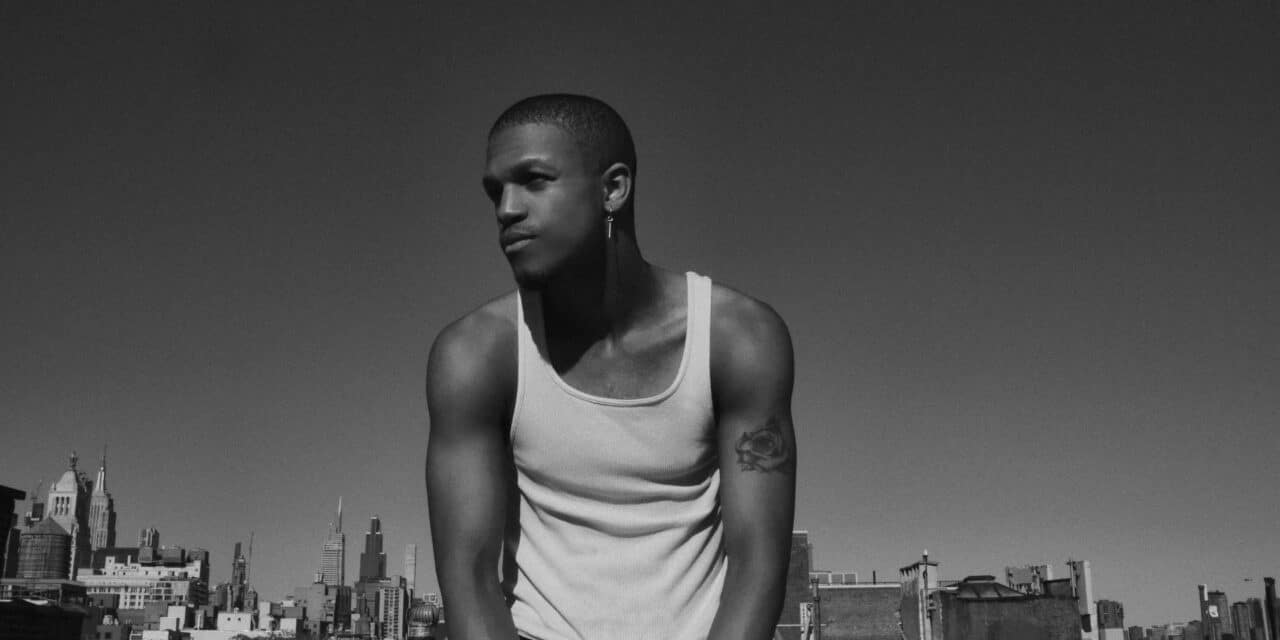

Dali Rose: born Drake Hunt, he’s a 22-year-old from Atlanta. He’s the son of Grammy winner Van Hunt, so you can imagine the kind of musical vibes he grew up with—think The Ohio Players, Sly Stone, Nina Simone—and then he throws in his own love for artists like Earl Sweat.

Even though he was always around music—he even sang in the church choir—Dali didn’t fully dive into it until his late teens, during the pandemic. He switched his major from Poli-Sci to music at NYU and really threw himself into production and songwriting. His debut mixtape Heaven is a journey through themes of love, abandonment, and hope in a dystopian world.

Your debut mixtape Heaven explores deep themes like love, abandonment, and hope. What inspired the concept behind it, and how does it reflect your personal journey?

It was supposed to be a random writing assignment that blossomed into this vision of an apocalyptic reality where all the nations’ marginalized are hoarded into ghettos with steel walls—no one in and no one out. At the edge of North Philly, one of these communities is ironically called Heaven. It was inspired by the fascism of modern American oligarchy, how it seems the crux of their worldview is a complete abandonment of the working class: gutting our schools, bankrupting us at the doctor’s office, and revoking any promise of our children inheriting a sustainable future.

In my own life, Heaven was a reminder to never give up hope, even when every glimmer of joy has been taken away.

Growing up with a Grammy-winning father like Van Hunt, how did his music and record collection influence your sound and artistic vision?

I’ll be honest, my father has never been one for a huge record collection.

But the dude is phenomenal. His music transcends any boundary; it dares to express the rawest emotions, by any means necessary. That’s been my greatest lesson from him—both within this creative process and across every walk of life. I must express myself.

You originally pursued a degree in Political Science at NYU before switching to music. What was the turning point that made you fully commit to your passion?

I became disillusioned with the political process, nihilistic even. I’ve always cared about the world around me—how it functions, how it can be improved—since I was old enough to think analytically. Year by year, all hope I had for the community around me was eroded by false promises. I watched democracy begin to die.

It became abundantly clear that the greatest change wouldn’t happen through media talking points and picket signs. It would happen in the home, in our relationships, and in the fabric of our culture. What do I have to say… as a man, as a breathing, loving human on this planet? Those are the questions I’ve begun to answer, and some of those dialogues have now been put to record.

You’ve cited artists like Earl Sweatshirt, King Krule, and Mac Miller as inspirations. How have they shaped your approach to songwriting and production?

What I admire about all three is their ability to construct worlds with their own hands, depleting every tool at their disposal. None of them have regimented music training; they’ve relied on their ear and the depths of a feeling.

The worlds they’ve created with such a grounded process are often heart-breaking, lined with so much grit that it’s, at times, incomprehensible. But it’s REAL. It’s honest. That’s something you can never take away from those artists: they made a statement built on integrity.

In a world of capitalistic pressures to produce a digestible product, that’s what I respect the most about them. Whether it’s diluted, easy-listening, or the grittiest soundscape you can fathom, it’s true to their heart. THAT is inspiring. It’s what kids like me needed.

Your music has been described as “the quiet sharing of a great secret.” How would you personally define your sound, and what emotions do you aim to evoke in listeners?

It’s tears of joy at a funeral. It’s a gut-wrenched butterfly.

I capture complicated feelings: being so lost that you’ve drowned at the bottom of the ocean, and now you’ve made yourself a home, locked off in the depths. My sound is fluent in all types of languages; it blends and translates depending on the story. I want whoever listens to be whisked away, to peer into this world with fresh eyes.

The world you built in Heaven is dystopian, walled-off, and emotionally heavy. Do you see your storytelling as a form of escapism or a reflection of reality?

It’s both.

I’ve been through some shit—used some substances a little too much, beat up myself a little too much. The therapeutic part of songwriting, worldbuilding, etc… yeah, it was penicillin for sure. But any escapism has roots in reality. It may be disturbed, discolored, and re-manufactured, but it stems from a picture of my everyday.

It’s a picture of my story, my community’s story, our nation’s story.

You sang in the church choir growing up. How has that early experience shaped your vocal style and the way you approach music today?

What’s funny is that singing with the church, or even with the school choir, never taught me technique. That’s something I had to develop once I needed it—learning to sing live, learning to play keys and sing. Your technique has to be sharp (diaphragmatic breathing, etc.).

Yet, like you said, it honed my style and approach. There’s nothing quite as versatile as traditional gospel: there are shades of jazz, blues, rock, classical, and even bluegrass or country. There’s complicated music theory and foot-stomping, hair-raising rhythm with a lineage tracing back to the fields. It’s an all-encompassing music education.

It was also fun as hell. It’s so ingrained in my style that I forget it’s there—until one day I’m watching myself grab the microphone, belting at the top of my lungs, ordering this sweaty Brooklyn dive bar to clap their hands.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while creating Heaven, and how did you overcome it?

There were times where I lost faith in the vision. I doused those mixes in gasoline and set them on fire. I stripped the ballads—nothing but synths and vocals. I wanted people to hear the grit, feel the pain, soak in every drop of this world.

Maybe it isn’t digestible. Maybe this apocalyptic, depressing collection of tape hiss gets two streams… I realized… who gives a fuck?

This was the vision, and I saw it through the best I could. I’m proud of myself. And I’m gonna do it again and again as I continue to grow.

Your music finds light in darkness. What keeps you motivated and inspired, even when exploring difficult themes?

It means the world when you hear someone else going through the same shit as you. You feel seen.

There are millions of us out there who spend each and every day feeling invisible. The type of music I listened to growing up… it was dark, raw pictures of trauma. Maybe that isn’t for everybody… but for kids like me?

I mean, it saved my fucking life.

So that’s what motivates me: for the people who feel invisible, who need a reason to make it to the morning… I’ll lay my heart out, and maybe we make a connection. That’s what it’s for, really. Otherwise, I’d keep these songs to myself.

Once that connection is made, I’m fulfilled—I made something beautiful out of destruction.

What’s next for you after Heaven? Any upcoming projects, collaborations, or live performances fans should look forward to?

I’m out here every week—playing gigs across New York: at your favorite dive bar, on a random rooftop, in your random venue down the block… so just follow me on IG or whatever and head out to the next one. Live music is where it all comes together for me, and I’m damn proud of the work we’ve put in. I wanna share it with the world.

Tour coming soon.

After Heaven, there are two EPs right down the line: Where Them Flowers Grow and Toys Killing Toys. They’re both an expansion on this world from Heaven—more ebbs, more flows, higher peaks and lower valleys, more uncensored storytelling.