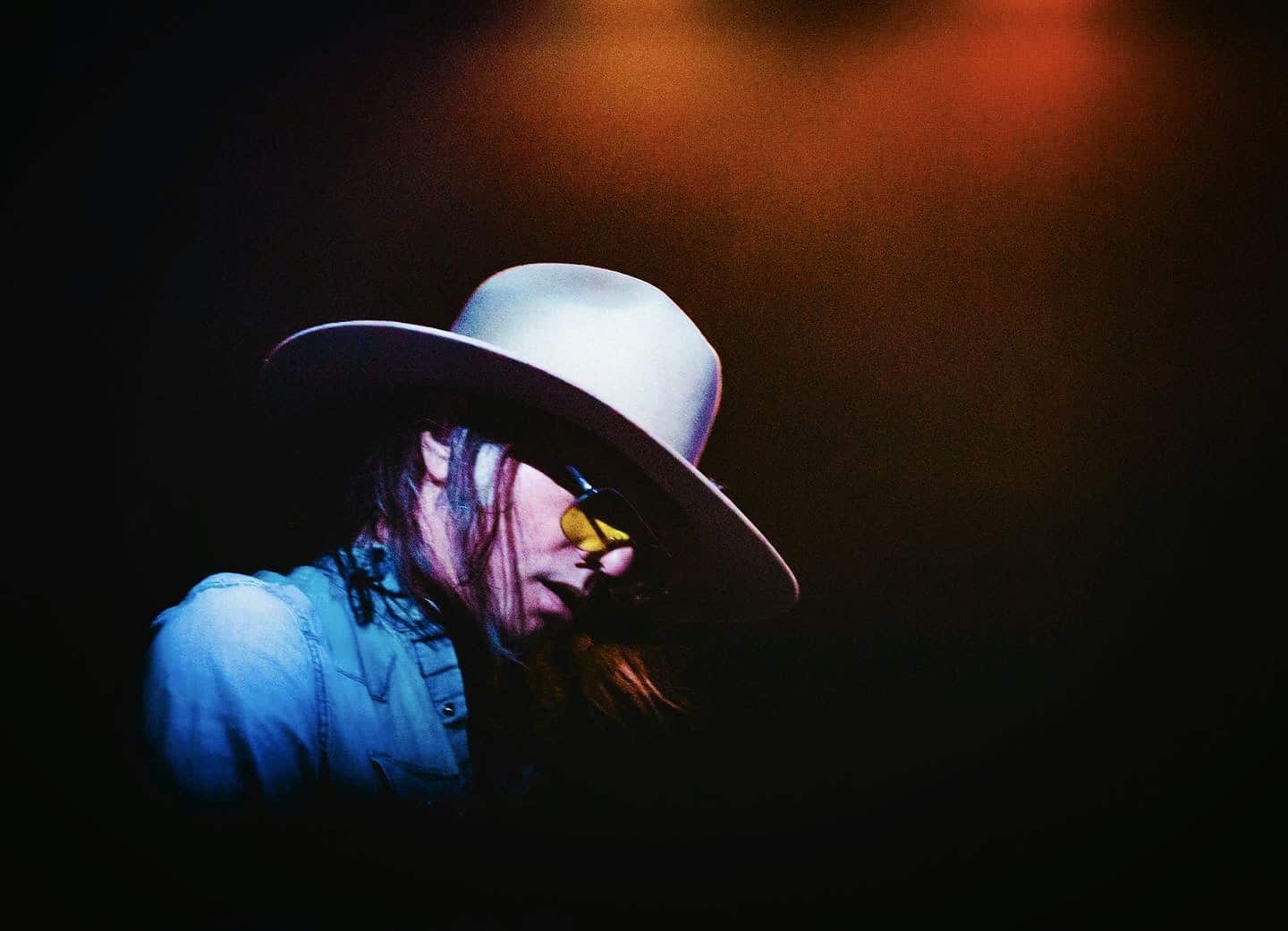

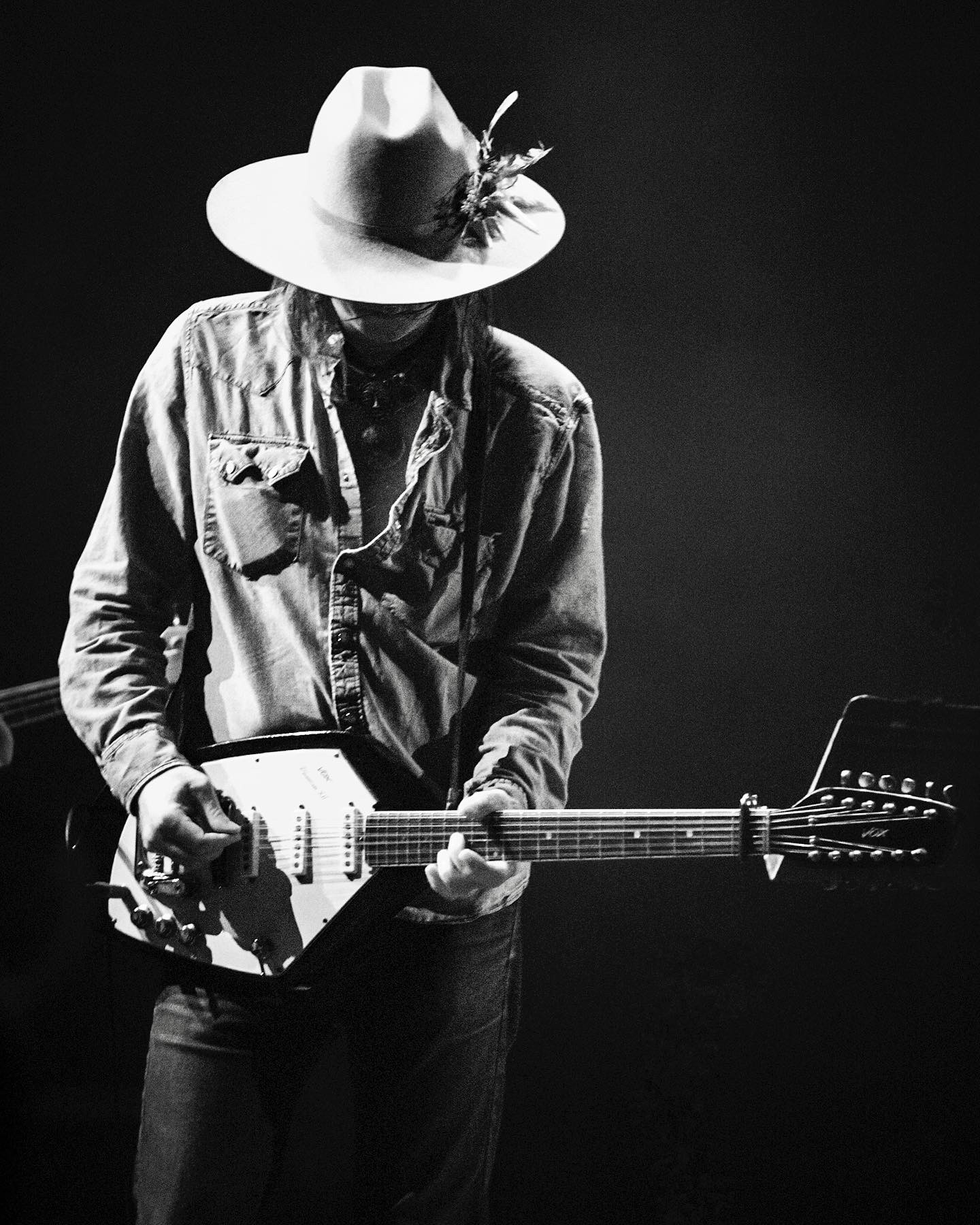

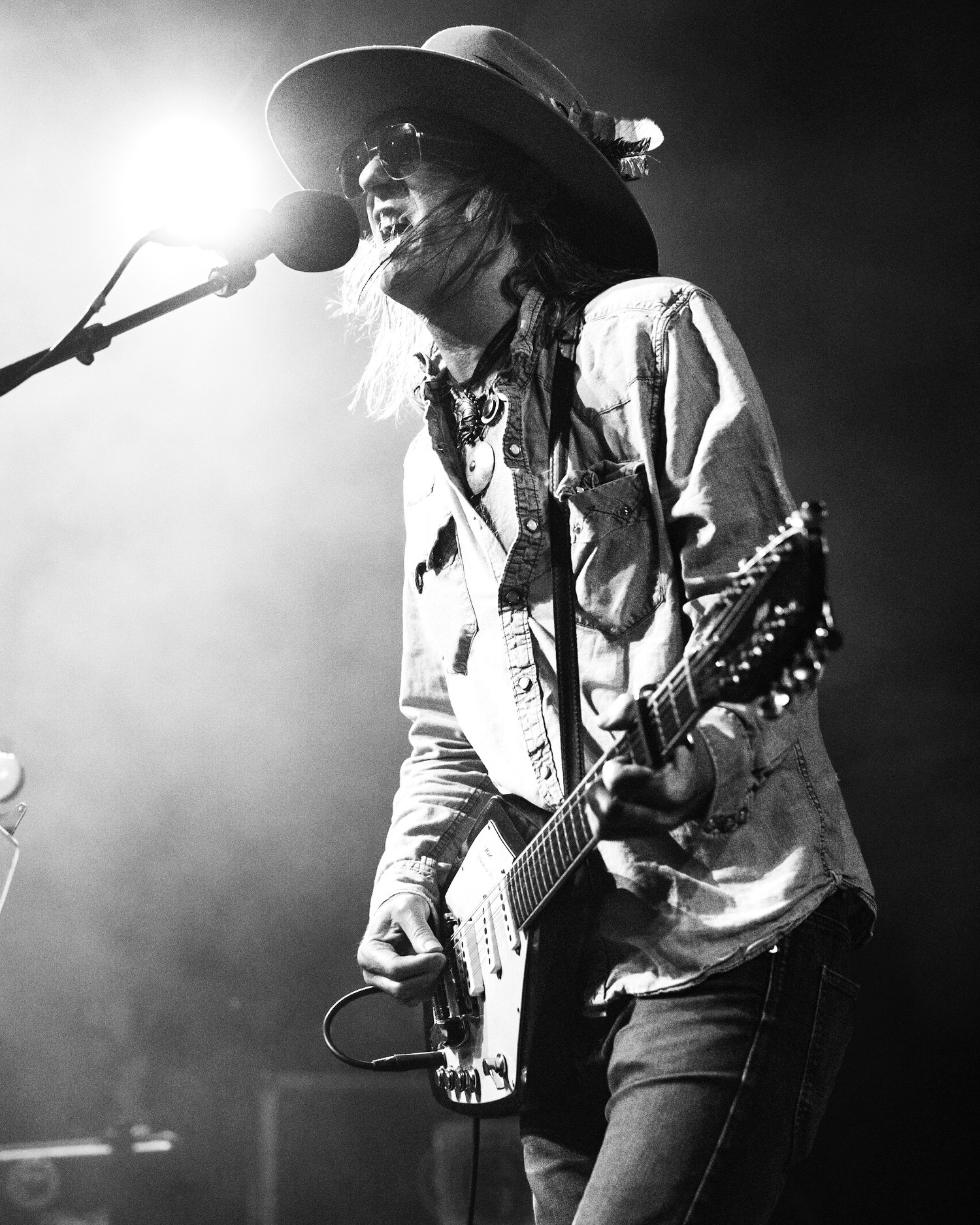

Photo Credit: Lauren Krohn

The San Francisco-bred band has been preaching this gospel since the early 90s and have maintained their place as one of the very few bands whose message has never changed or been watered down over the course of a career.

They remain the equally unrighteous and self-righteous monoliths of modern psychedelic rock, echoing visions of the past but with an uncompromising confrontation towards the future, against any industry imposition, for the sake of love and music. No major labels, no compromises, no fucking bullshit.

The band’s leader; Anton Newcombe, operates as the conductor of a rock orchestra. Straddling the line between meditation and altercation, playing with sensations of tension and release, poised on the edge at all times. The songs collapse and build themselves up again better. The band themselves are intentional in this, as they are with everything else. With a career spanning almost thirty years and twenty-two albums, they are, inarguably, very good at it.

Mundane: What do you think makes a great live performance?

Newcombe: It depends on the context, okay? Because, somebody who’s a consummate entertainer, like in modern pop music, there’s all these things happening, right? It’s not really based on the music; it’s based on the experience of everybody coming together, coming to dance and doing their thing. So you’ve got like K-Pop and stuff, where they’re not even singing they’re just jumping up and down, but it’s the whole, being there together. And even like…They’re selling these tickets, you know, Taylor Swift had these cheap tickets, right? With no view of the stage whatsoever.

Mundane: But they’re in the room together

Newcombe: And people don’t mind! It’s them being out and being able to see it. So, that’s one thing, right? And then people like James Brown, that were like, super-entertainers in their high point, doing all these moves and stuff, that’s another thing. There’s another kind of music, like folk music, it’s for our time. It could be anything, like in the history of culture, that goes all the way back I think.

Mundane: Where do you think your band falls in?

Newcombe: I’m more interested in that, in things that bring people together and hold them together over time. Creating culture, but not in the sense that it has to be so big, like when you look on the outside of, say, “The Nirvana Phenomenon” or where everybody is like, look what Run-D.M.C. did to music, like everybody wearing tracksuits and doing graffiti. It doesn’t have to be that kind of cultural changing.

Mundane: but it could just be something that exists in the room?

Newcombe: something that empowers people! You know? And there’s certain things that happen, even with people in the 90s, it doesn’t matter if it’s The Breeders or whatever, like Kim Deal’s process encouraged more women to play instruments, do you know what I mean? Certain people come along, and it doesn’t matter who it is, whether it’s like PJ Harvey or something, but there’s the people, and it’s successional, you know, people that sort of straddle both worlds. So you’ve got the lords, like Lana Del Rey or something, and she’s in this pop thing, but also just doing her own thing? And all that stuff is really important. Influencing culture that way. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that to 1000 people on their iPads in their bedroom, that it’s necessarily “good entertainment.”

Mundane: Also, with Lana vs. Kim Deal, it’s more tangible inspiration to pick up a guitar than to sell out an arena like Lana. Dreaming about that kind of fame is a lot less doable than being in a rock band.

Newcombe: But it isn’t even desirable! I think some people might think that performing at the Super Bowl halftime would be the pinnacle, right? But to just be lip-syncing? Barely moving but having like 500 people moving behind you so it looks like you are? It’s no different than in the UK, they used to have Top of the Pops, which was basically the rundown of the top twenty songs, and everybody’s lip-syncing, everybody is just miming. It’s weird, I don’t know. I like to just play music and try to overcome the shortcomings, because there’s always something. It’s so ephemeral.

Mundane: Shortcomings with your own band?

Newcombe: Yeah, because people change, and some people are better…just better musicians than others.

Mundane: How do you think you’ve changed since the band started?

Newcombe: Well, uh, I don’t know.

Mundane: That’s alright

Newcombe: But that’s a good question. I don’t know; I don’t like to…I’m not really concerned with…

Mundane: Minding the past like that?

Newcombe: More or less projecting my own opinions of myself and what it means. I mean, I can tell you why I do something, but I don’t need to give any hints about anything.

Mundane: I understand.

Newcombe: Like, to what it means or what its value is…

Mundane: What’s something that’s value you think has been underestimated?

Newcombe: Well, there’s all this stuff, right? There’s all these people; they’re like the old guard in the establishment. A lot of people in the music business, it doesn’t even matter if I’ve sold way more records than they ever sold in the 60s, but they’re like-

Mundane: They’re the legends.

Newcombe: Right, and part of the thing, it really doesn’t matter to them. I’ll never get any kind of credit because I didn’t go through the whole thing, and sign my life away, and do everything that I was told to do, and reach this acknowledgment. It’s like it isn’t valid or something. I even had to deal with the US government because I play with a lot of Europeans, I was trying to get visas for them, and they told me, “You need to print out all the articles you can find about the band” So we print out like 20,000 reviews, and it was like, fucking hell right? And they said, “No, you’re not a real band; we’re not gonna give you these visas because you aren’t a real band.” Just because we aren’t on a major label. And I’m like, this is absurd.

Mundane: So do you feel betrayed by the music industry?

Newcombe: No, because I told them to fuck right off. Because I knew everything about it, but it’s really interesting, they say “you’re just fucking up your career,” but this isn’t my career. That’s all, just something strange…it represents a lot of different things to me. But the thing that I knew was that the industry was bullshit. And we’ve seen it, you know? Time and time again.

Mundane: And did you know that going in?

Newcombe: Yeah. I mean, that’s how I knew that I could accomplish what I wanted to accomplish, which is basically to be able to go anywhere and play my music and have it pay for itself. But just saying “No” to everybody. I knew that would work easier than just everybody saying yes.

Mundane: What’s been the best memory of your time with the band?

Newcombe: Hm, I don’t know, I don’t really have favorites, but you know, a lot of times things are really, extremely touching. We go to South America and all these places, and we’re not a TV or radio band right? So to have thousands and thousands of people on the other side of the world singing your music, it’s really, really touching. It’s annoying but it’s touching.

Mundane: Why is it annoying?

Newcombe: Because you know, it’s like a football stadium, where they’re all there and the crowds are singing, especially in Europe where they’re all like…

Mundane: Like the chanting.

Newcombe: Yeah, and you’re trying to play music, and it’s very hard.

Mundane: But that’s what we were talking about, with people more being in the moment than it being about the songs.

Newcombe: It’s good, it’s good. There’s been lots of places and lots of times where that happens. It makes me feel really…positive.

Mundane: What do you think it takes to be a progressive band now?

Newcombe: I just think that every single person falls for the same exact line and goes for the same deal. And they all get flushed down the toilet equally fast. I just think that everybody…it’s insanity. Everybody’s relationship with the music business is exactly the same, and they think for some reason that they’re gonna be the only one that’s gonna skate through it. It’s so crazy.

Mundane: Is writing a more emotional or technical exercise?

Newcombe: It’s both, but the most important thing about writing is that you go through the process of confronting your fears and just jumping into it. To be creative is to be free to just play without deciding whether the outcome is good or bad. And being open to where that goes with that freedom. But there are technical aspects to it, formulas or whatever.

Mundane: With the last record, what was it that you were confronting?

Newcombe: Well, the context of everything was all this fucking existential crisis everybody was dealing with.

Mundane: Because of Covid?

Newcombe: Yeah, that was the big one. But in general, there’s much more attached to the way the world is changing than just that. I was mostly interested in reaffirming to myself how I want to be and how I view things. And that’s also a good thing; I mean, you could…sharing your perspective is a valuable thing if you actually are a creative. That’s why it’s important to…I don’t know, sorry.

Mundane: I’ve wondered about that a lot, about if it’s a conversation between the musician and the listener, if it’s a shared perspective or two separate experiences.

Newcombe: Well, that’s true because, like, I never wanted to be like anyone that I’d ever met or knew of until, through the arts and music, I found that I didn’t feel different anymore.

Mundane: You felt like you were part of a community?

Newcombe: No, but I knew there were people like David Bowie or any of these people that…It doesn’t matter who it is, Bob Dylan or anybody…But they were just all the way them, and that was okay, and from that, I could figure out my own life, too. Like it didn’t matter that I was different from everybody, that it’s not better, you understand that it’s part of the process. And there are other people that go through the same thing. It’s different now because a whole thing with pop music is the fashion and everyone just trying to fit in…

Mundane: But that’s other genres too, like punk or whatever…We dress this way, and so we sound this way…

Newcombe: Exactly.

Mundane: Do you think solitude is necessary for the writing process?

Newcombe: For me, it is. I mean, I spent a lot of time in cafes, being around people, hanging around in bars…And obviously playing.

Mundane: But it’s not helpful anymore?

Newcombe: I’ve just done all those things. For me, I really enjoy just being by myself and just thinking. Going through whatever it is.

Mundane: Is there a certain idea you’re trying to figure out?

Newcombe: When I get working really fast, there’s two ways I can write: I can write whole songs that just stand alone and come out of nowhere, or I get on a roll, and it’ll be like seventy or two hundred songs at a time…And then I put it down. I have to physically stop. I don’t go, “This is fucking amazing; I’ve got the Midas touch; literally, everything is good, I better keep going!” No, I stop, and I go “That’s enough.” And I have no idea whether I’ll be able to make up anything else ever again.

Mundane: In those moments, you think that you might be done?

Newcombe: I think that it’s important that I do. That it always might be done. To battle yourself and your doubts, from the beginning, like a teenager going, “Oh, I don’t even think this is good; everybody is gonna hate it, fuck this sucks, I’m horrible.” Just to have to walk through that fire every single day. And to get really in tune with the idea like, Is this really what I wanna do? It’s good energy to move forward.

Mundane: When you’re in those moments when you think that “this might be it.” What do you think about doing when the band is over?

Newcombe: Well, I don’t have to do this….I enjoy playing music, but I don’t have to do this. It’s quite difficult, you know? It’s hard to stay healthy, for me to travel this much, I just get worn out…I was worn out when I started….It’s so much work.

Mundane: What’s the best part of touring?

Newcombe: Well, it’s all very…Ephemeral. You’re just someplace, like today I’m in New York, and In a few hours I’ll be someplace else. And it’ll just gone. It’s like smoke.

Mundane: How do you want the band to be remembered?

Newcombe: I don’t know…I don’t care really…Is that a good ending? Is that bad? I mean, what is it that everybody is talking about? That we’re all gonna die? Burn in a painful death very soon? Least of my worries about what people think of my band when I’m ninety.

Mundane: I think I go the opposite way; when everyone says everything is gonna burn, I overvalue the things that are here now.

Newcombe: That’s true! It is true, but what’re you gonna do? Build like a pyramid mausoleum? Something? It’s a smart way to go, you know…if you have like a normal sort of nice headstone at a cemetery, if your family doesn’t keep paying on the plot eventually it falls away and they get rid of it. But if you build one of those big fuckers…you’re not going anywhere.

The Brian Jonestown Massacre are defined by their relentless pursuit forward. After conversation with Anton, that much is clear. Joel Gion is a true believer in his own band and all they’ve stood for over the course of their career. He’s been there since the beginning, playing tambourine and shakers on stage while balancing Anton’s penchant for severity with a wry sense of humor and unflinching calm. He is part of the noise himself, the messenger and the message.

As the band moves forward he’s been directing his own attention back towards the past with a new project. Earlier this year he announced that he would be publishing his first book, a memoir titled In The Jingle Jangle Jungle, which is set for release this upcoming February and available for pre-order now.

Mundane: Do you write for fun, or was this the first time you’d really sat down to do something like this?

Gion: I do write for fun, yeah, there was no teeth-pulling. When you get my age, you want to remember those times and how cool shit was, it was a different world then where things were, you know…cooler, and we were all just going for it. Like, fifty things would happen in the course of one day because you’re just like, “Now where do we go, now what do we do? We’re going to this dude’s house? Okay, cool.” And then you go to that dude’s house and do whatever you do there…it’s not like now where you’re just kind of waiting around for the one or two things you have to do that day.

Mundane: Do you miss those times though? Because back then you were fighting.

Gion: Back then we were fighting, yeah. And you were just trying to sus out…everyone’s in competition, you know? There was this really big music scene, and everybody was writing music and trying to be the most interesting and trying to…we’re all vying for the same calendar dates from the clubs, we’re all vying for the same music magazine articles, and there’s only so much room. So we’re all in competition, and so everyone was very much on the move twenty-four seven. And then I just did all these fucking drugs at the time…And I got involved with this whole like DEA bust situation because like, this was the time of illegal raves, right? So I was going to all these illegal raves, and I lived in this warehouse where, you know, I’d get sent to the FedEx to ship off three hundred hits of ecstasy to Florida…

Mundane: Were you selling?

Gion: No, no, I was not a part of the business end; I was kind of the mascot of the place. So I could be partied out twenty-four seven, but I wasn’t making any money on it. I would lay sheets of acid to pay my rent and bills, so I would do two books of LSD with the eye dropper so then I had a place to live, had a room to be in. But that eventually got busted by the DEA so…This is all going on at the exact same time that like, Take It From The Man and Satanic Majesties and all these classic records are happening…so A’s and B’s.

Mundane: And did you know how major those records were going to be as this was happening?

Gion: Yes, all the entire time, all the way through. I knew that I’d gotten into the best band in America. I knew it was a matter of time, and I was just, you know, evangelizing the cause because I knew it, because we were, and it turned out to be true.

Mundane: I asked Anton about this. Is there a message you’re trying to send with the band?

Gion: Well, it’s just the spirit of…I don’t wanna say rock and roll…But I wanna say the spirit of doing your own thing, in your own way, and everybody can like it or they can fuck off, and everybody should live that way.

Mundane: Do you think people can still live that way now?

Gion: It’s a lot harder; I think it is a lot harder. I think within yourself, you can, and you are in control of what goes on inside of your vessel. Whether or not you can make that a thing is very hard…it’s so much harder.

Mundane: What’s your favorite memory from it all?

Gion: Memories are hard…The best memories, you know, it’s so cliche like, “the best memories are the ones you don’t remember, if you were there you weren’t really there” but I don’t know, it’s hard to say, it’s been such a long time…decades. But my favorite kind of era would be the brokest we possibly ever were. Bumming around and playing songs on Haigth street, trying to get cigarette money.

Mundane: Was it actually fun at the time, or is it just fun looking back at it?

Gion: it was always fun. Because you always knew…you always knew.