“I’m kind of relieved that people don’t need to feel guilty anymore about seeing somebody nude.” Timeless fascination with human physicality and artistic depictions of nudity as a reflection of our reluctance to be controlled.

The social imaginary of the Western world, complicated and heterogeneous as it may appear, includes a few elements that have penetrated it so strongly that they are now set in stone and universally considered as its deep-rooted, essential components. Marilyn Monroe in the white dress. The Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower. The Mona Lisa. And, much more fundamentally than the aforementioned, the ancient statues. It is really hard to think of those distant times that have come to function as the source material of the entire Western aesthetic system without imagining the marble, hard, sleek, perfect bodies. Aside from becoming a reference point for our beauty standards, the ultimate expression of health and wellness, those bodies provide reaffirmation for the pillars of our humanity itself: this is what a person looks like, and it’s beautiful. Indeed, our fascination with our own physique seems to be as old as the history of civilization itself, making the ultimate point about the self-obsession inherent to the human species. Yet another proof that anthropocentrism underlies the very roots of our behavioral patterns, and so, if we are to ever deconstruct it, we should start from shifting our perspective on quite everything we know to be true and undeniable. But that’s a story for another day.

The point here is that the physicality of the human being, and the nakedness of the latter as the most absolute manifestation of the first, has been imprinted in our understanding of what it means to be a person. Being aware of your body comes in a package deal with eating with your mouth shut and speaking politely to strangers, all presented to us as ideas necessary to adopt to be considered a functional member of the society. And yet, we’ve undoubtedly come a long way since Ancient Greece, where the naked body was not only very often depicted in art but also actively encouraged when practicing sports (to decrease movement restrictions and increase the possibilities of muscle work analysis). As much as we are still intrigued by our nudity, we are now expected to cover it up practically at all times, implying a somewhat ironic dynamic in which what is our most natural, universally shared condition is also something we feel very uncomfortable exposing to others. Nevertheless, or maybe for that very reason, it has not ceased to mesmerize us completely, as evidenced by the continuous and steadily rich presence of nudity in art: from Rubens to Manet to Helmuth Newton, the multiplicity of depictions across different periods points to the timelessness of the nude as subject matter, regardless of the varying but never absent element of controversy it entails.

Speaking of controversy, there is something deeply counterintuitive about the fact that featuring nudity in visual forms of creative expression is such a controversial topic in the first place. Why exactly are we so simultaneously appalled and excited by the image of a naked body when all we have to do to see one is, technically, look into the mirror before taking a shower? Being the most primal condition in which human physicality can appear, nakedness deprives us of layers of protection normally provided by layers of fabric: social conventions and norms, allowing certain behaviors and restricting others. Without them, we’re exposed with nowhere to hide, forced to face our respective truths, which is never a comfortable practice. That discomfort explains the taboo: it’s both slightly disturbing and rather exhilarating to watch secrets being revealed.

That complicated duality of sensations triggered by the artistic display of nudity is precisely what erotica plays with. Not only does it take on the subject matter in question in the most straightforward way, but it exploits it even further, challenging the viewer’s shock threshold with one element eventually associated with the nude: our sensuality. Interestingly enough, the common thread across erotica artists, at least in its photographic manifestation, comes down to what has already been mentioned, that is, the quest of the truth. It’s not the controversy itself that they find exciting; it’s the conditions of unmasking and liberation that it creates.

The work of Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, known for his bold representation of the female form, while highly polarizing among the audience because of its explicit sexual saturation, is seen by the critics rather as a reflection of the artist’s strong dedication to reality.

Christoph Gerozissis, one of the collaborators for Araki’s recent exhibition at the Meredith Rosen Gallery in NY, calls it the photographer’s “hunger to document his life, every aspect of it, from love and death to the red light district, a taxi ride through Tokyo, to the clouds in the sky.” Simon Baker, director of the MEP (Maison Européenne de la Photographie) in Paris, talks about “the impression of a free play between the anecdotal or the everyday and the studied pose or composition, between, as it were, his real life and his ‘artistic life’,” inherent to Araki’s entire visual oeuvre.

“Nowhere is this more at stake,” he adds, “(…) than in his presumably insatiable appetite for photographing the female form, both in situations of presumed intimacy and of extreme and often explicit artifice.” Araki is just one artist among many to have come to the same conclusion: our nakedness, as well as the carnality and ultimately the sexuality associated with it, are parts of our lives that erotica helps uncover, forcing the viewer to face his vulnerability. And the ongoing public fascination with nude photography suggests that the audience actively seeks that power play. We enjoy it.

Jurgen Maelfeyt, Belgian creative director and founder of the publishing platform Art Paper Editions (APE), has been dealing with art books for more than a decade, one of his many areas of interest being precisely erotica and other forms of nudity depiction. A graphic designer by education, APE is now his main professional occupation. He releases around twenty publications per year, some of which are his own creations, but the majority come from other authors. While most of his publications have to do with art photography, Maelfeyt doesn’t want to be exclusive and expands the range with other techniques and concepts. “There’s no real criteria,” he says. “The selection of our books is very subjective. A lot of them start by simply talking to people.”

Dealing with the nude in numerous projects, Maelfeyt remains quite unaffected by the supposed controversy around this subject matter and explains that for him, it’s just a means that conveys a message on a different level. “I have nothing against nudity whatsoever,” says Jurgen. “It has always existed in art, and to me, it isn’t really different from any other topic. But I think there’s always something deeper than just nude portraits or pictures of people having sex. I take on projects that explore this underlying layer; I am not interested in publishing just very sexy books that feature explicit nudes and go nowhere beyond.”

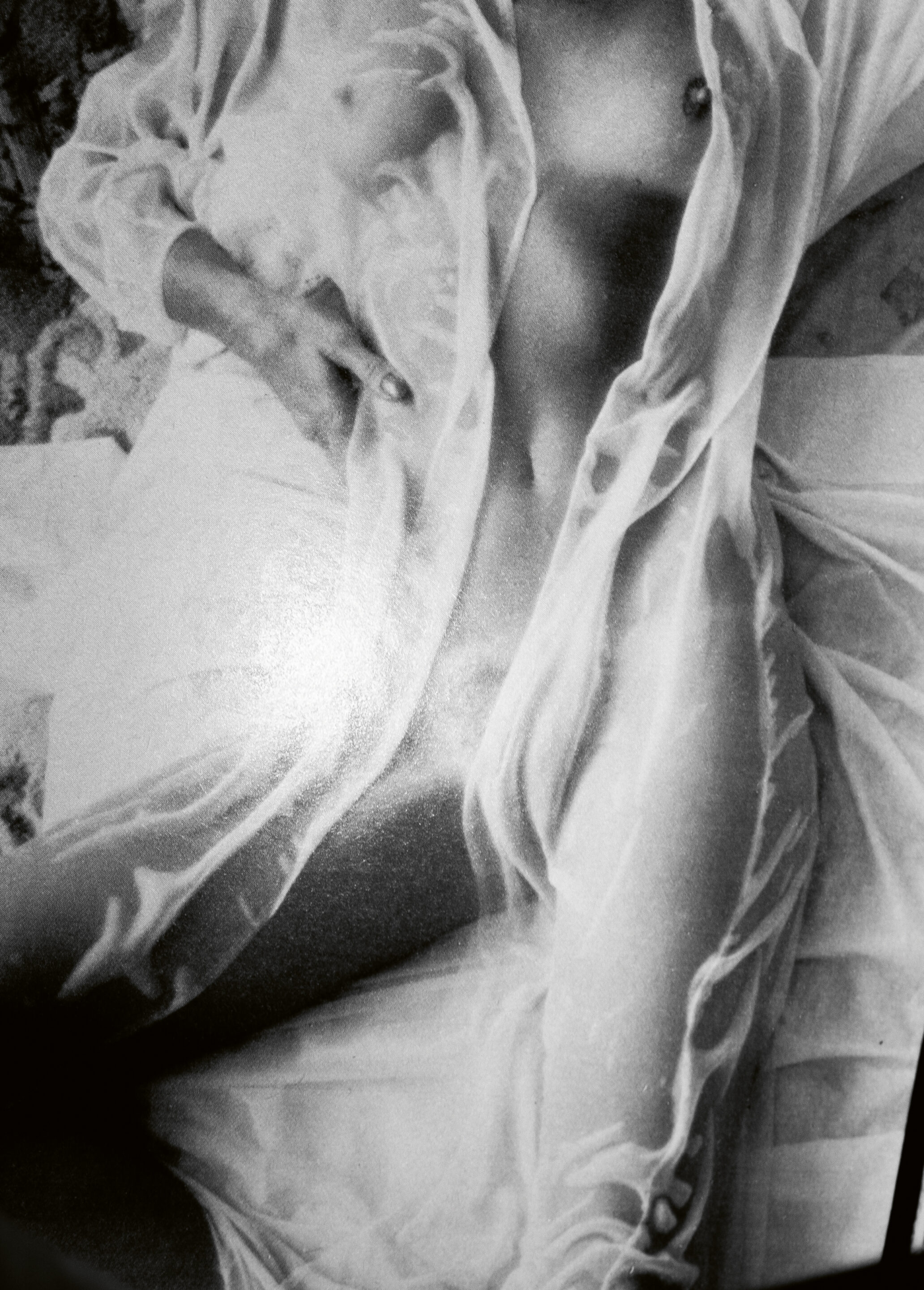

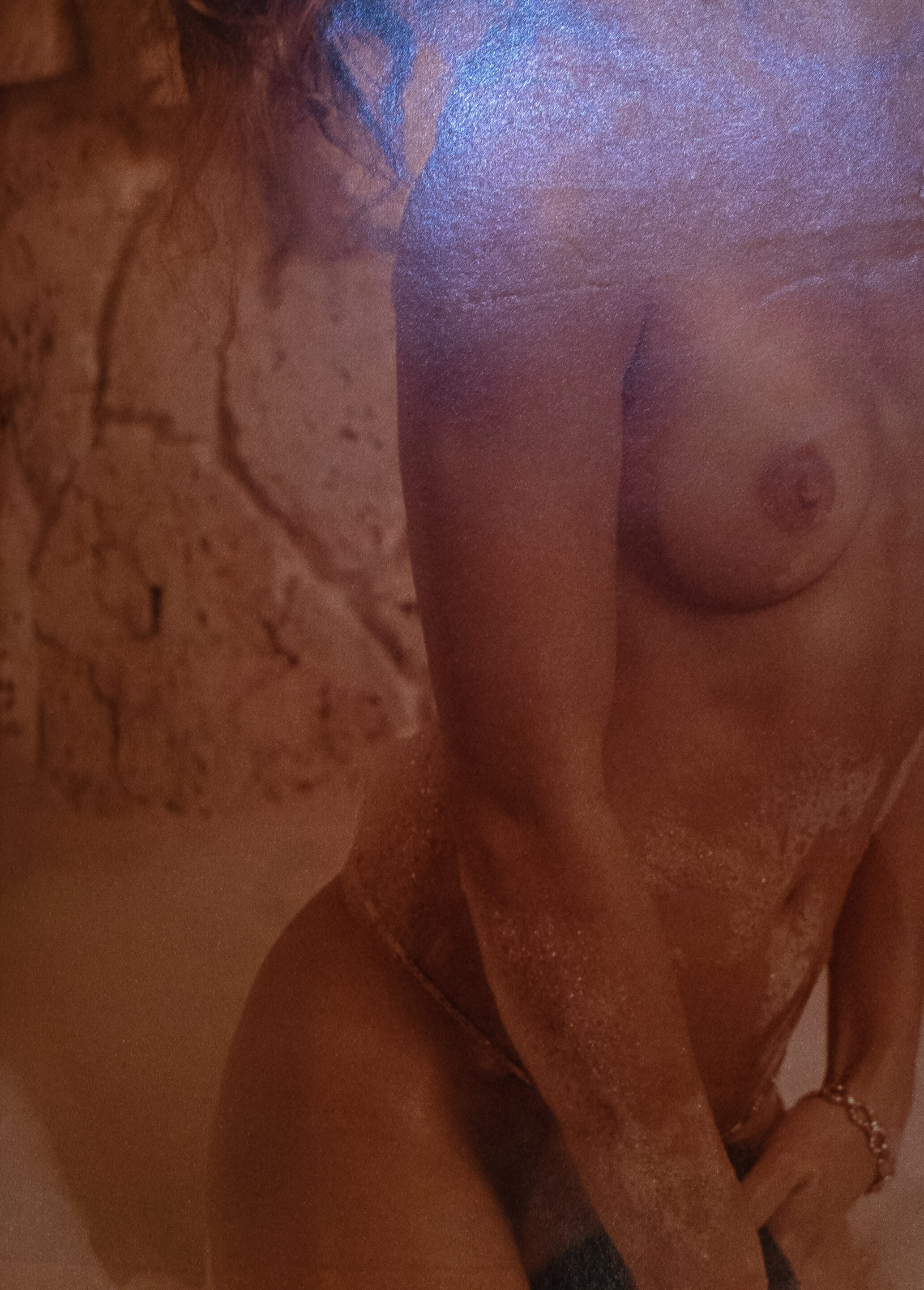

A series of his own publications, FURS (2019), WET (2021), and TOY (2024), is a good example of that approach. Choosing vintage erotic photography as the main theme of each book, he gathered pictures united by the visual thread indicated by the respective titles. In terms of creative process, Maelfeyt rephotographed pictures found in adult magazines from the 70s, opening up a dialogue in which redefinition plays a pivotal role.

“I collect old Playboy magazines, and I noticed that fur was a very common motif in erotic photography, especially in the seventies and maybe a little bit in the eighties. So I rephotographed them and used fur as a theme for the first book. Then I acquired some more issues and realized there might be a second theme: wet. I use vintage magazines as a source material, but I don’t see this project as archive work, because I completely change the images. Many people don’t even know it’s Playboy.”

As one might expect from his expressed unbothered attitude towards nudity, the author’s principal point of attention for the project resided somewhere else, namely, in the printing paper: “They used to print magazines not on glossy paper, which is standard practice today, but on matte paper, which makes the fiber visible. I used direct lighting to highlight that. I also did a lot of manipulation in terms of color to achieve the effect that interested me. I guess what I’m saying is that it’s not all about eroticism. Of course, it is about eroticism in part, but it’s also about different things. I could have simply scanned those pictures, but I didn’t.”

The series is a marriage of two presumably unrelated ideas, passion for printing techniques and the anachronistic appeal of vintage erotica, that gives place to a fresh, playful take on the aesthetic associated with the latter. Soft and warm color palette, close-up shots, and of course the lighting that brings out the qualities of the paper create an effect that goes very far from the male-gazed obviousness of the original source. “I think in most cases, the explicit element of the image is removed. I tend to, for instance, direct the light where the erotic tension would be. I remove the explicitness of the images, but I also think that by doing so, they become even more sensual, precisely because of this element of subtleness.”

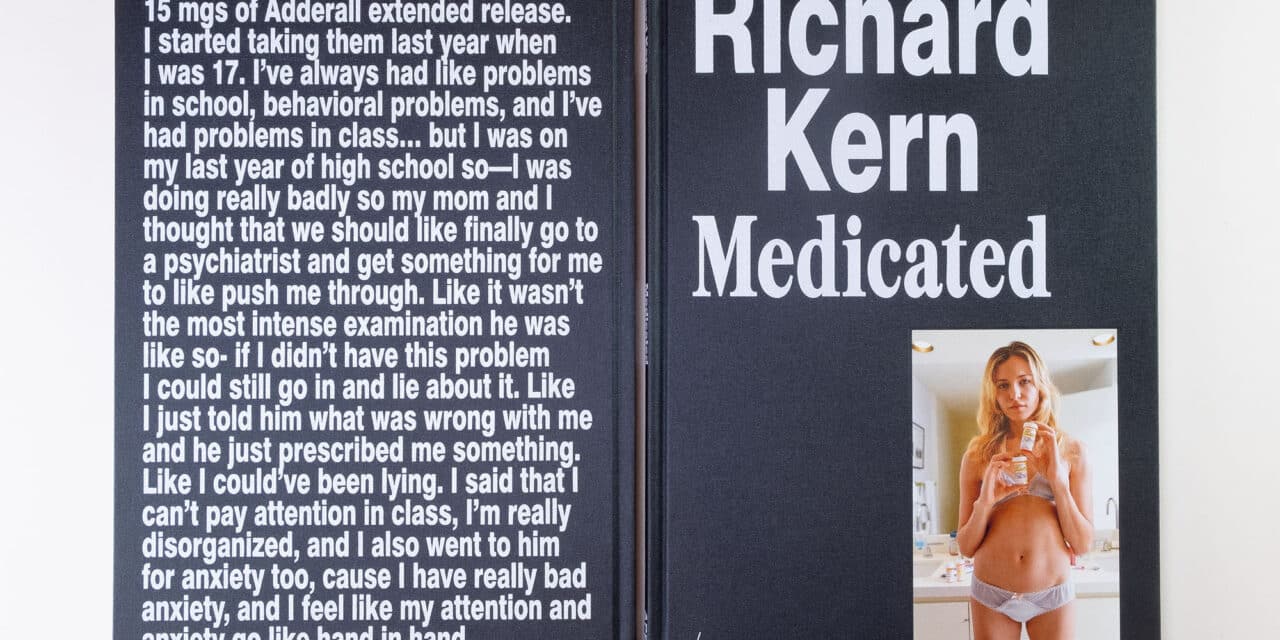

Interpreted in ways as numerous as the depictions themselves, nudity seems to serve a higher purpose, being used rather as a means to reach it than a goal in itself. The same is true for another APE publications, Medicated by Richard Kern.. It tells the stories of young girls struggling with prescription drug addiction and juxtaposes first-person accounts of the protagonists with their portraits, posing with pill bottles in their underwear or topless. While not without a controversial factor, especially given the age of the depicted, the use of nudity here tells yet another story: showing the vulnerability of these girls, it exposes the imprudence of the pharmaceutical industry. Whether our personal sensitivity allows us to fully interact with the project or not, it definitely offers a completely different take on the representation of the naked body, demonstrating how it can sometimes be entirely detached from mere fascination with the human flesh. On a more local note, the history of Medicated supports an observation of mine confirmed by Maelfeyt: that the public interest in nude photography is currently experiencing a shift.

“The book was released in 2020, which coincided with the peak of the Me Too movement. So when it first came out, it was a flop: nobody would buy it, the distributor had problems with it, etc. I think people started associating nudity directly with abuse. But for about a year now, the mood has changed. I took the book with me to Offprint in Paris last November, and it was my best-selling publication at the fair. A book that’s five years old! So there’s a general shift in the sense that people are not afraid anymore, which I find very important. I think Me Too is a good thing, of course, trying to fight the abuse, and it’s definitely not over yet. There still is too much abuse. But I’m kind of relieved that people don’t need to feel guilty anymore just about seeing somebody nude.”

From oversexualization to desexualization to normalization, the presence of nudity in art will probably never stop sparking debates. If anything can be concluded about the multiplicity of forms it takes and messages it tries to get across, it’s the intrinsic link to the social climate, varying in space and in time. Nudity magnetizes people, it scandalizes them, it catches their attention. And as such, it becomes both a party and an object of public discourse.

“The rising awareness around Me Too has also led to intensified censorship on Instagram, which is a problem for many artists for whom this platform is the main advertising medium,” concludes Jurgen Maelfeyt. “Instagram controls nudity, and people don’t want to be controlled. So they go against it, hence the increased interest in erotica among creators. Instagram has no authority over the publishing world because it’s something very physical, something that can’t be blurred.”

What Maelfeyt meant as an expression of his frustration over a situation affecting his work makes for a surprisingly accurate comment on our complicated, emotional relationship with depictions of nudity: maybe it’s not about the fact that it exposes our complex reality, our sexuality, or even our vulnerability. It’s about the defiance of control it symbolizes. In the end, regardless of the individual motivations and paths, what every human being strives for is freedom. And we will strip our clothes off if necessary to achieve it.