The collision of artistic voice, psychology and cold analytic medical procedures may seem strangely forced together. Although when artistic creativity stretches beyond its societal set boundaries the result far outreaches our preconceived notions. Some may call it grotesque, others that it encompasses a glimpse of craziness, but I would refer to this artist’s sculpture design as an unapologetic documentation of an individual reality.

Sequentially, this is unfetteredly expressed in the exploratory practice of Olga Noronha, Portuguese designer whose conceptual and artistic methods are interwoven with the philosophical investigation of medical-surgical procedures. The detailed observation of the body and the fascination of tapping into the human subconscious reaction to foreign bodies permeates most of Noronha’s projects: Noronha conceptually explores psychology and orthopedic methods, takes the conceptual product to a team of engineers and doctors, and creates an object that touches the grotesque and the delicacy of the human body.

The collection of Noronha’s sculpture- designs goes beyond the conceptual notion of accessories with objects that re-image the human body and have medical applications; A creation of a visual experience beyond the documentation of fashion – reflects the need of the artist to shatter the conventional interpretations of art practices.

Speaking with Noronha it is clear that her visual aesthetic and conceptual realms are profoundly connected. Deep diving into her background and influences, here Noronha explains the core discourse of her practice and leads us through the atmosphere of being a designer of medically prescribed jewelry.

Joana Alarcão: As an introduction for the readers who don’t know your practice, can you describe it?

Olga Noronha: I’m a former jewelry designer and graduated in Jewelry Design, but I soon started directing my practice into sculptural works and medical investigation. I move very much between pragmatic fields of science, engineering and conceptual art while creating sculptural pieces and design-led works. I very much divide my time between science, design, sculpture, jewelry, and research.

J.A: In your bio you mention that your practice “aims to combine scientific pragmatism and conceptualism of art.”, can you elaborate on this line of thought?

O.N : As a designer-artist and as someone that does research together with engineers and doctors – because my parents are doctors and I’ve lived my whole life knowing about medical techniques – I have several projects that join both disciplines. What I do is bring psychotherapeutic art and design together to rethink medical subjects towards allowing the patients to have personalization aspects throughout the treatment time.

J.A: How do you incorporate medicine, science, and arts in your designs specifically?

O.N: Conceptually, I research about the capacity, time and aspect of a patient’s recovery when he is subjected to, for example, a hip replacement. When there is a “foreign body” that needs to be inserted into someone’s body so that they regain the quality of life they had previous to the injury. But in fact, that object it’s usually emotionally rejected by the patient because it doesn’t belong to the body. I’ve taken this situation and my welfare knowledge of medical techniques and started thinking, what if I can turn this into somehow a pleasurable emotional situation.

So instead of having a lump of metal, that is highly technologized and highly engineered that does come with a certain aspect of pain, what if it becomes a canvas? What if the patient, instead of just being subjected to the introduction of a metal medical piece, does have the hypothesis of customizing it, of making it their own?

What I do is join medicine, engineering, and art design. Art in the process of thinking about the medical process and the process of beautifying for emotional purposes; design in the fact that we have to redesign the medical objects towards the liking of the patient/client; medicine in the application and the mechanical thought behind it.

J.A: Can you tell us about any recent work?

O.N: Currently, I’m working almost every day on the continuation of the project called Medically Prescribed Jewelry. It’s between body modification and medicine. I’ve received a grant from FCT (Foundation for Science and Technology) to take some of these works, in this case not hip replacements, but bone plates, to the laboratory to get tested. I currently have a team of approximately five to six people – designers, engineers, one medical consultant, and one orthopedic doctor.

J.A: Can you lead us through your artistic process? What are your normal steps from an idea to the finished piece?

O. N: It depends if you are talking of the finished piece as a product or a finished piece as a concept. My current project is an embryonic project which still has a lot to go. However, I started it, not the biofiligree degree specifically, but the medically prescribed jewelry in 2011. It was under this theme that I did my master’s and my PhD.

In 2010, in my last year of the BA in London in Jewelry Design, I wanted to do something challenging, not for others, but for me emotionally. I have a childhood trauma with needles. I decided that what better way to cause myself a huge challenge than to try to overcome that trauma and that fear of needles by doing a project about needles. So that’s very much how it started. I collected a lot of surgical instruments that my father designed a good few years ago and I started looking at them as a designer and conceptual artist to see their potential. What was felt through looking at those cold materials called sterile materials, and how could I turn that into something else?

I chose to start the project, which was called Conflict- Rejection- Attraction. There is a psychiatric term called conflict attraction rejection- very Freudian thinking that goes, first, you feel attracted by something, but you then get fed up and rejected. My idea here was exactly the opposite. It was a conflict, starting first by rejecting and then feeling attracted – these are needles, but I actually can make them beautiful and wearable as jewelry pieces at the same time. I developed a series of needles that you could inject yourself, take blood, and have vaccinations with but also turn into earrings and brooches, replicated in golden diamonds.

That led to such strong reactions that I thought, well, this may be a way for me to explore other areas of medicine and other areas that produce objects for surgical and medical applications that bring fear to people. It all developed through that. It wasn’t any longer, the Conflict – Rejection – Attraction, it turned into something much broader called Medically Prescribed Jewelry. My idea was never to make something that was purely speculative. It was always to do something that with further study could be applied to medicine.

J.A: What can you tell us about your performances?

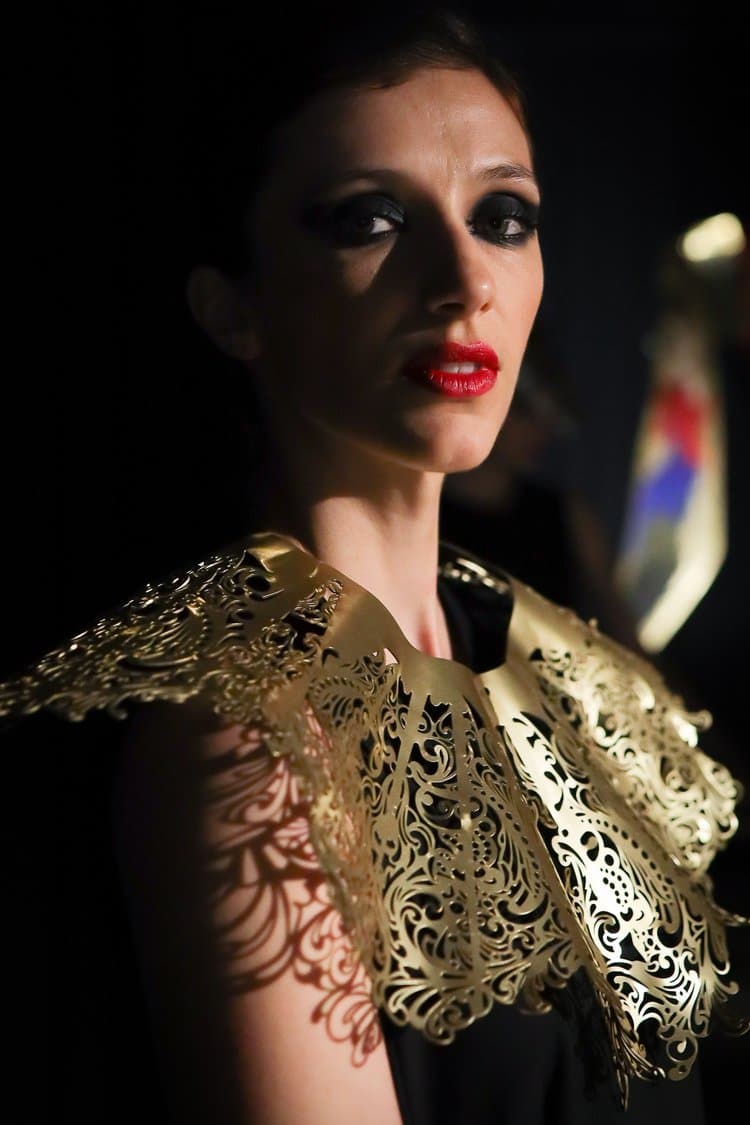

O.N: I do two kinds of performances. Usually, when I do an opening about Medically Prescribed Jewelry in which I take the medically prescribed jewelry out of their exhibition set and I placed them onto the body so that people understand that not only they are sculptural works, but that they can also be displayed at a home as a collectable or as a work of art. In those performances, the majority of the time the public and the audiences are put inside of the performance themselves without even noticing, which is quite interesting.

Then I do the performances within the fashion section. But nothing to do with fashion. The thing that happens is there is an opportunity. There is a stage. There is an audience. The audience at first was not understanding my ideas. They were set to look at fashion, but suddenly they realized that what I would be presenting was a surprise moment in which they didn’t know what to expect in terms of materials, settings, presentation, and wearable skills.

The only thing I have in common with fashion is the body. My inspiration is the body, the physical body, and the behavior of the body towards another body, towards society, towards a space. There is nothing about styles. There is nothing about tendencies.

J.A: Your work is showcased in several public and private collections, among which are the Museo del Gioiello di Vicenza (It), MUDE Museum (Pt), WOW Museum (PT), Goldsmiths UL art/design collection (UK), Central Saint Martins Museum (UK). How did some of these partnerships begin and how do you feel about the experience so far?

ON: I live for that experience very much as you may imagine. When we speak about private collections, we speak about private collectors that approach works that are already made.I don’t work with galleries currently because I do sell directly from my studio for quite high values.

The collectors not only came to the studio, but they actually asked, for example, I have one great collector right now that met me the other day saying “I have two fireplaces at my house that I’ve never used. And I want them to be occupied by an installation by you.” This is the most defying and challenging work for me, which is seeing the space, creating something, and making a

proposal to a client. I’m not presenting what I’ve already done out of my own inspiration and interpretation of a matter. I have to design something for a space that every day those collectors will be experiencing.

It’s a very interesting and very beautiful relationship because I don’t think of the many clients and collectors as only that. They are on top of the things that I produce and that I create and then purchase the ones that they feel are the best ones.

In terms of the museums, usually what happens is if I present something in a performance or exhibition, I get contacted by the director and the director purchases the piece for the museum collection.

J.A: As a Portuguese designer would you say you are influenced by Portuguese culture and art? Any particular designers?

O.N: I wouldn’t say in terms of art but in terms of culture. In some of my works, I am influenced, it’s inevitable to say, by Filigree and Fado. Although what I might be very influenced by is the Portuguese people. There is a tender-heartedness to the Portuguese soul. There isn’t a frivolous feeling but a very tense emotion. If you think about Fado, we feel a lot, we’re deep. It’s about very strong feelings. It’s not about floating on water and going wherever, but it’s like, whatever we do for good or for bad, we do it strongly; we do it with our soul.

In terms of influences and inspirations, I would probably tell you, philosophy, psychotherapy, hypnosis, and science – they are the conceptual drives. Aesthetic drives- Renaissance and French Renaissance motifs, detailed art, or architecture. In terms of Portugal, more than aesthetic inspiration, I would definitely say the way that Portuguese people feel.

J.A: To conclude, where do you see your artistic practice evolve?O.N: Wherever destiny takes me. I don’t make plans, I never did. For a simple reason, if I make plans, there is a chance I can get disappointed because they might not come true. I plan my week. I don’t plan my month.

O.N: Wherever destiny takes me. I don’t make plans, I never did. For a simple reason, if I make plans, there is a chance I can get disappointed because they might not come true. I plan my week. I don’t plan my month.