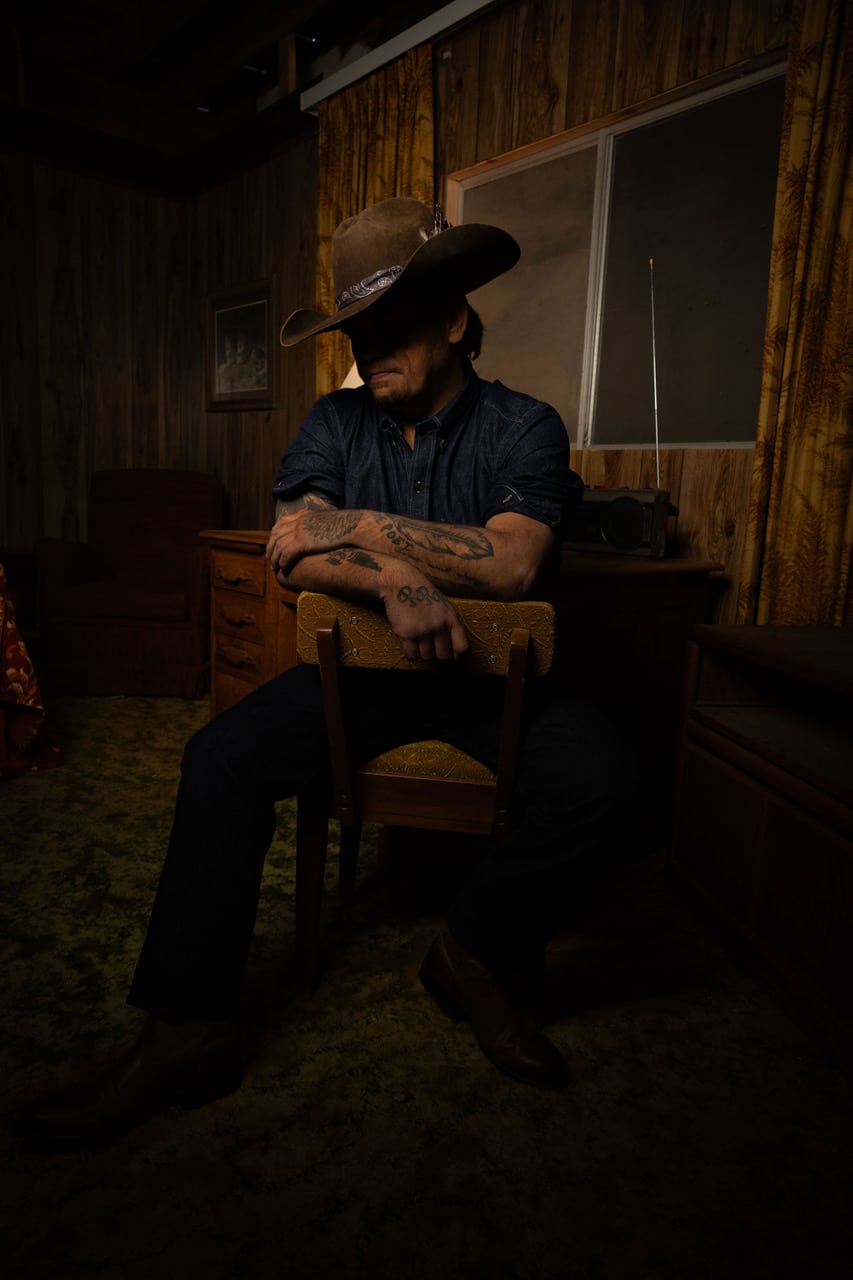

Some records are written in boardrooms. Some are written in five blurry, beer-soaked days with nothing but a room full of musicians, a few memories to burn through, and the kind of grit you can’t fake.

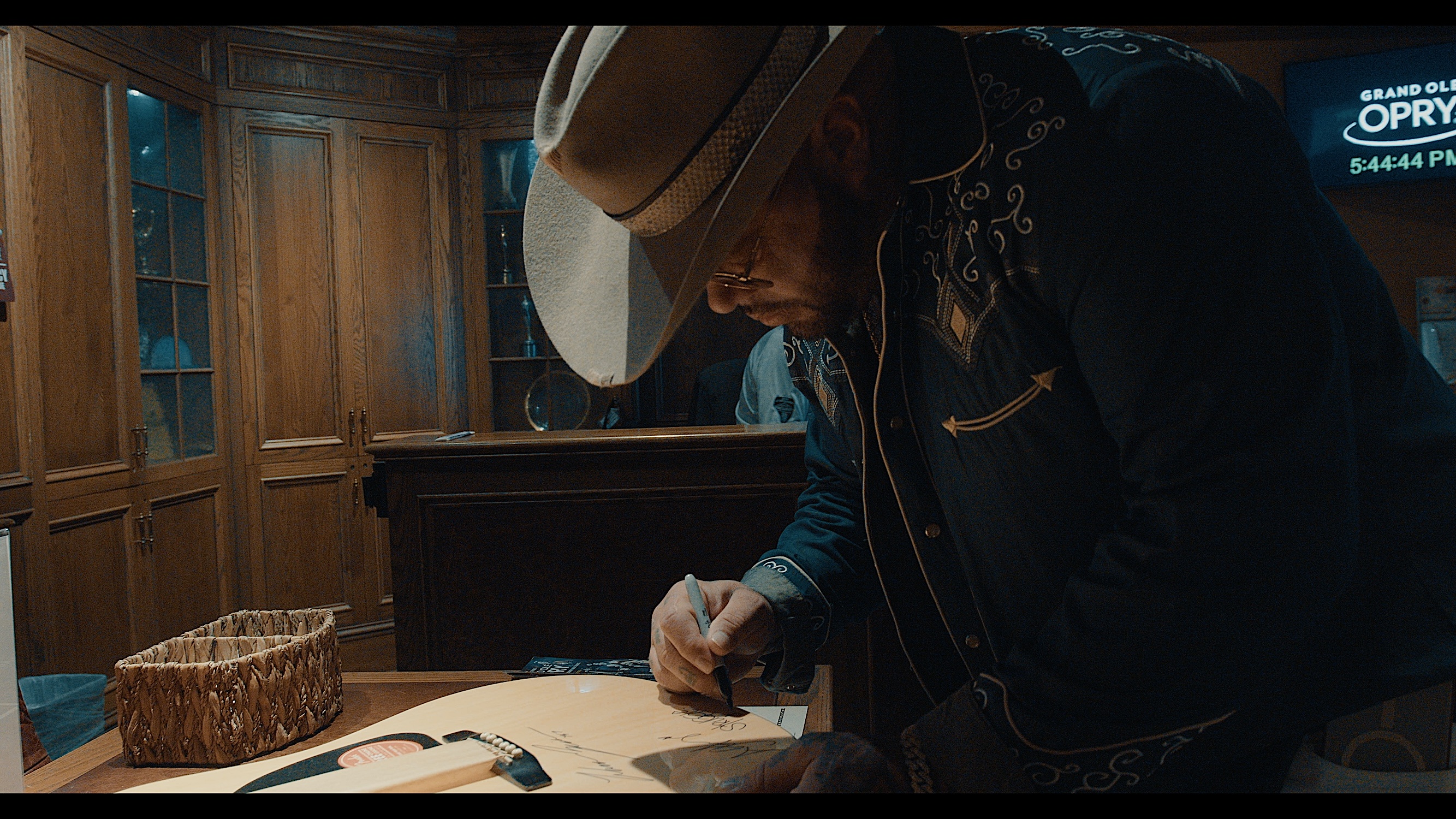

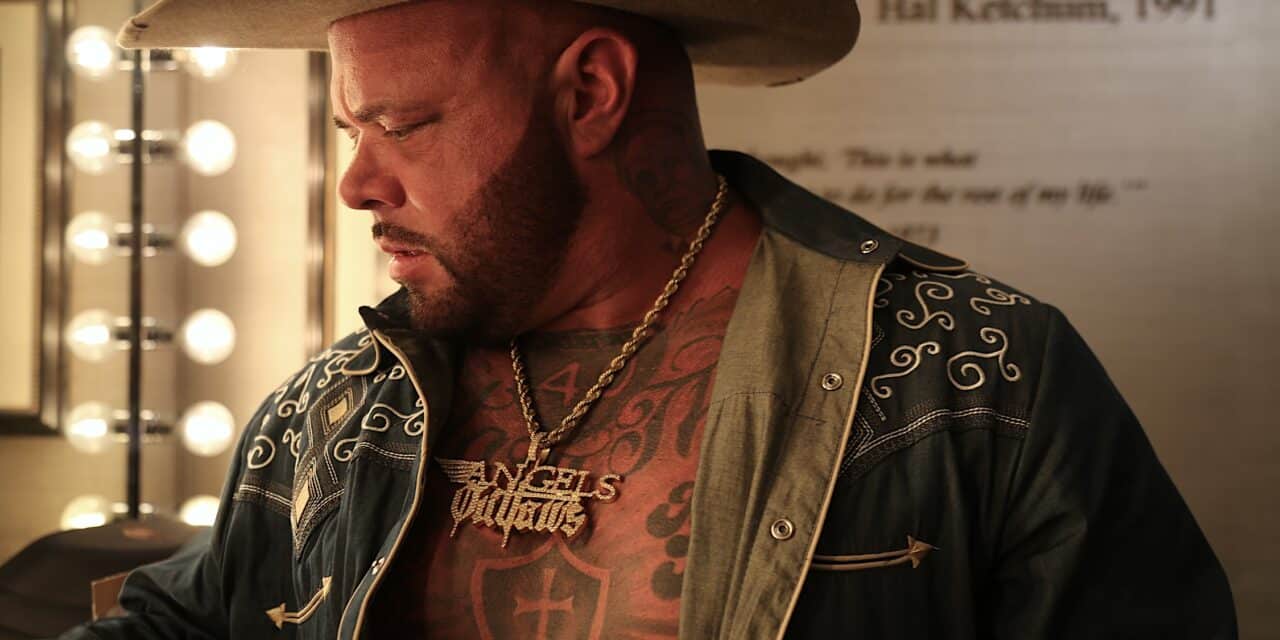

On July 18, outlaw country scion Struggle Jennings and Louisiana oil rig storyteller Bryan Martin give us the latter — a blistering, fiddle-laced single called “Don’t Play Your Games” (Average Joes/ Angels and Outlaws), the first taste of their upcoming outlaw-collaboration EP 1976, due this September.

A loose, defiant anthem full of stubbornness and soul, “Don’t Play Your Games” is pure country catharsis, with Struggle growling, “I don’t play your games, this town might drive a man insane…”, a sentiment you can almost smell on the barroom floor. This isn’t a slick Nashville product; this is two men in the room, writing their own truth, giving a Stetson-tip to the ghosts of Waylon, Willie, and every other hard-headed outlaw who taught them to stand their ground.

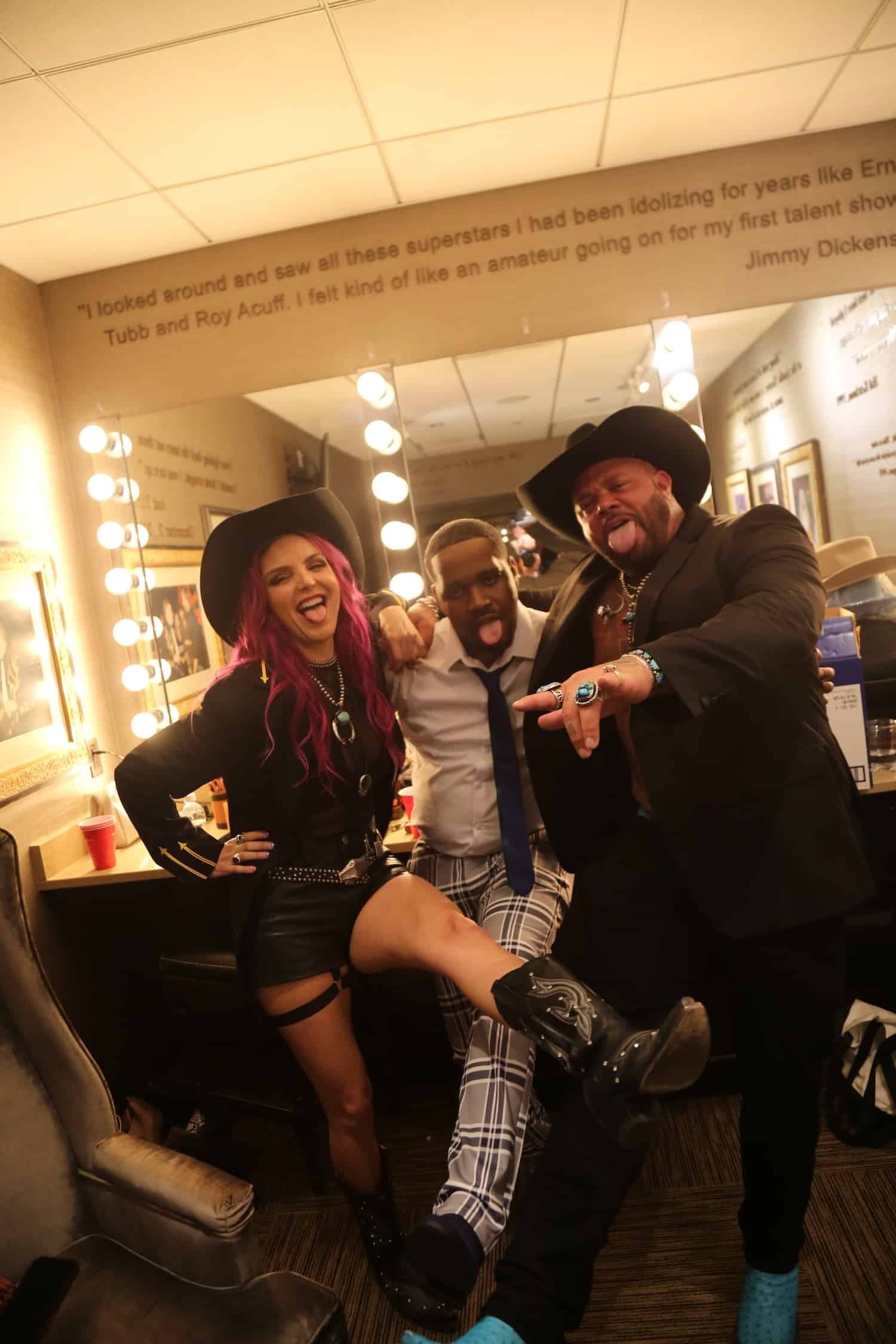

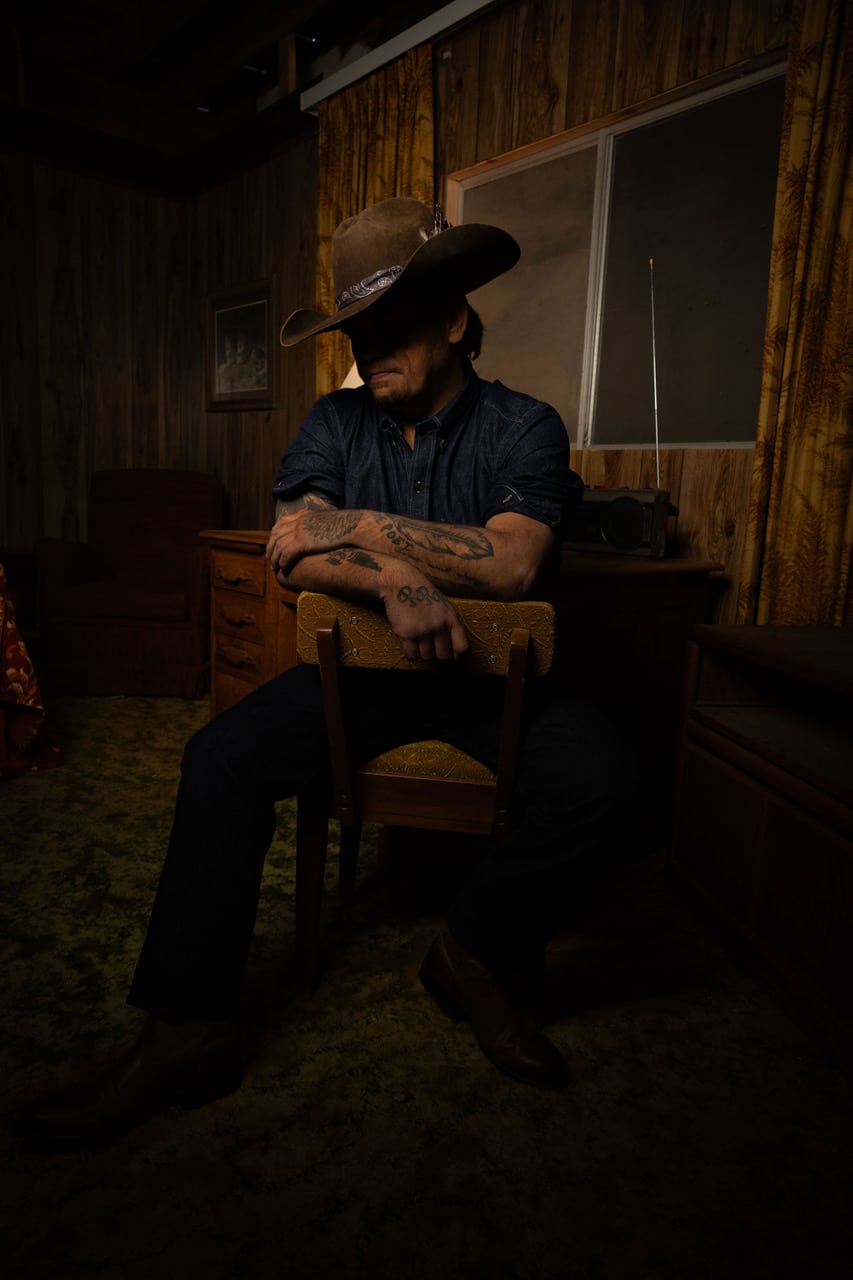

Both artists know what it means to walk the long way around. Struggle, the grandson of Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, is a certified Gold-selling country-rap revolutionary who clawed his way out of prison and into the studio, turning his West Nashville street scars into a new kind of country music: raw, unpolished, and unashamed. His collaborations with Jelly Roll alone have helped spark a cultural moment for hip-hop-inflected country storytelling. Bryan Martin comes with his own calloused hands — a roughneck who spent years working oil rigs while writing deeply human songs about hurt, hope, and holding on.

Together, they sound like old friends leaning against a truck bed at midnight, talking about the way this business — and this life — will chew you up if you let it. 1976, the EP they banged out in just five days, feels destined to join the lineage of outlaw records that don’t just tell you about freedom — they embody it.

Struggle himself puts it plainly: “This is about getting in a room, playing real songs with real people, and doing it our way. Nothing more, nothing less.”

If the single’s any indication, 1976 will be the kind of record that reminds you why country music still matters: because sometimes, it’s the only thing honest enough to stand in the fire and not flinch.

We’ve got our boots on for the full release come September. Until then, don’t play your games. Just play this.

When you walked into that studio for those five days to make 1976, there was no agenda—just two friends and some songs. What did that kind of creative freedom unlock in both of you that maybe you hadn’t felt in your solo work?

You know, when there’s no intention or you’re not going in with any pressure searching for a single or searching for a certain sound, there’s a special freedom to it. I try to do that in all my music. I never really go in and chase a single or look for a number one. I’m just whatever I’m feeling that day. Bryan and I together did the same thing, and it was pure and honest and real, and we were just two friends having a good time writing about what we were going through.

You named the project 1976 as a nod to Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and the outlaw movement. What does being an outlaw mean to you now, not just in music, but in the way you live your lives?

Well, you know me and Bryan are both two fellas that have had a rough life, overcome a lot, and have a deep-rooted passion and love for music. There have been many times in both our lives when we were chasing a dream that seemed way too far out of reach. I think we’ve both got that same outlaw spirit in us because we don’t fit in anybody’s box. We ain’t trying to be anybody else. We’re not trying to fill anybody else’s shoes. We’re just us. We’re not gonna sell out. We’re not going to follow anybody’s guidelines on what we should or shouldn’t be doing. We’re just making music and telling our story, and living our lives.

Both of you have lived through hardship and carried that grit into your music. How did your respective backgrounds—West Nashville and the Louisiana oil fields—show up in the sound and stories on this record?

Bryan and I realized real fast that the first time we met, we were two of the same people, and we’ve been through a lot of the same things, and it’s effortless. We sing about what we know and what we’re going through, so it’s gonna naturally come out, the grit, the hardships, the life, the story. So everything that you hear on the songs, the whole record is things that we were going through, have been through, just pieces of our life.

There’s something so vulnerable about making a record live in one room with the band, no safety nets. Why was it important for you to record 1976 that way?

For it to be true to the era, for it to be true to the feeling and the emotion and what we were going for, it had to be done that way. Hell, I would have cut it on tape if we had an engineer there that could have done it, but we just went in to cut a record, and as we were in the middle of the record, we were like This feels like 1976.

You’re both navigating careers that live outside the polished Nashville mainstream. What kind of sacrifices—or blessings—come with staying independent and rejecting conventional industry expectations

You know everybody’s got their dream, everybody’s got their path. I don’t knock anybody who goes the label route and wants to do that. I’ve brushed shoulders with a lot of labels, and I’ve got a lot of friends that have been signed to big labels, and you know I just ain’t found the right partnership with anybody that felt like they were gonna just let me be me. So, of course, you have the blessing that integrity is always intact, the music is always real. You’re not being told what you’re supposed to do or gotta do; you’re just doing you. It’s a great place to be as an artist. The downside is that it’s harder to get the proper marketing and promotion, and it’s almost impossible to get radio. The labels own a lot of that real estate and a lot of those billboards, and so it makes it more difficult to reach the audience that you’re trying to speak to. But I feel like if it’s good music and you’re paying the bills, that’s success to me.

Struggle, you’ve talked about “purpose over popularity” before. Bryan, you’ve sung about carrying scars that you can’t always hide. In what ways does this album reflect where you’re both at personally right now?

Well, I’m always writing and making music about where I’m at because I write each song about how I’m feeling. There’s a bunch of songs on here like “Don’t Play Your Games” that come from the last couple of years of kind of dancing with the country industry and brushing shoulders and being in this place and then realizing, man, I don’t know if I want all that. Songs like “Fell Off The Wagon”, Bryan and I are both talking about overcoming drinking problems and trying to be better, and you know, stay out of them bars and them honky Tonks. Songs like “The Night Has Got Me Now” that are talking about real-life stories, things that I’ve been going through or went through recently, you know, or ” Real Ones” talking about how we feel right now. So every song on there is a glimpse into the last few years of mine and Bryan’s life and the things that we’ve been dealing with.

The outlaw country tradition has always been about storytelling that’s messy, human, and true. Are there any moments on 1976 that scared you to put on record, because they hit so close to home?

No, not at all. I’ve always done that. You know I’ve been completely transparent. It’s a fine line. I was dancing for a long time because my goal is to try to show people that you know they don’t have to drink or do drugs and criminal activity, but my testimony is that all this stuff that I’ve gone through and all the stuff that I’ve overcome, I’m still not perfect. I still make mistakes, and every one of these songs reflects things that I battled with, and I ain’t scared to show it.

What do you hope younger artists and fans take away from watching two guys like you write, record, and release something this raw, with no filters?

Well, you know I feel like everything has its cycles, right, and everything that was once old is new at some point to the next generation. I hope that a lot more guys are just getting back to it, especially with all the AI stuff now, all the you know people using heavy tuning. I hope it inspires some kids to get back in there and just make some music, just get back to practicing in your garage and get back to cutting records, just raw and real without all the extra shit.

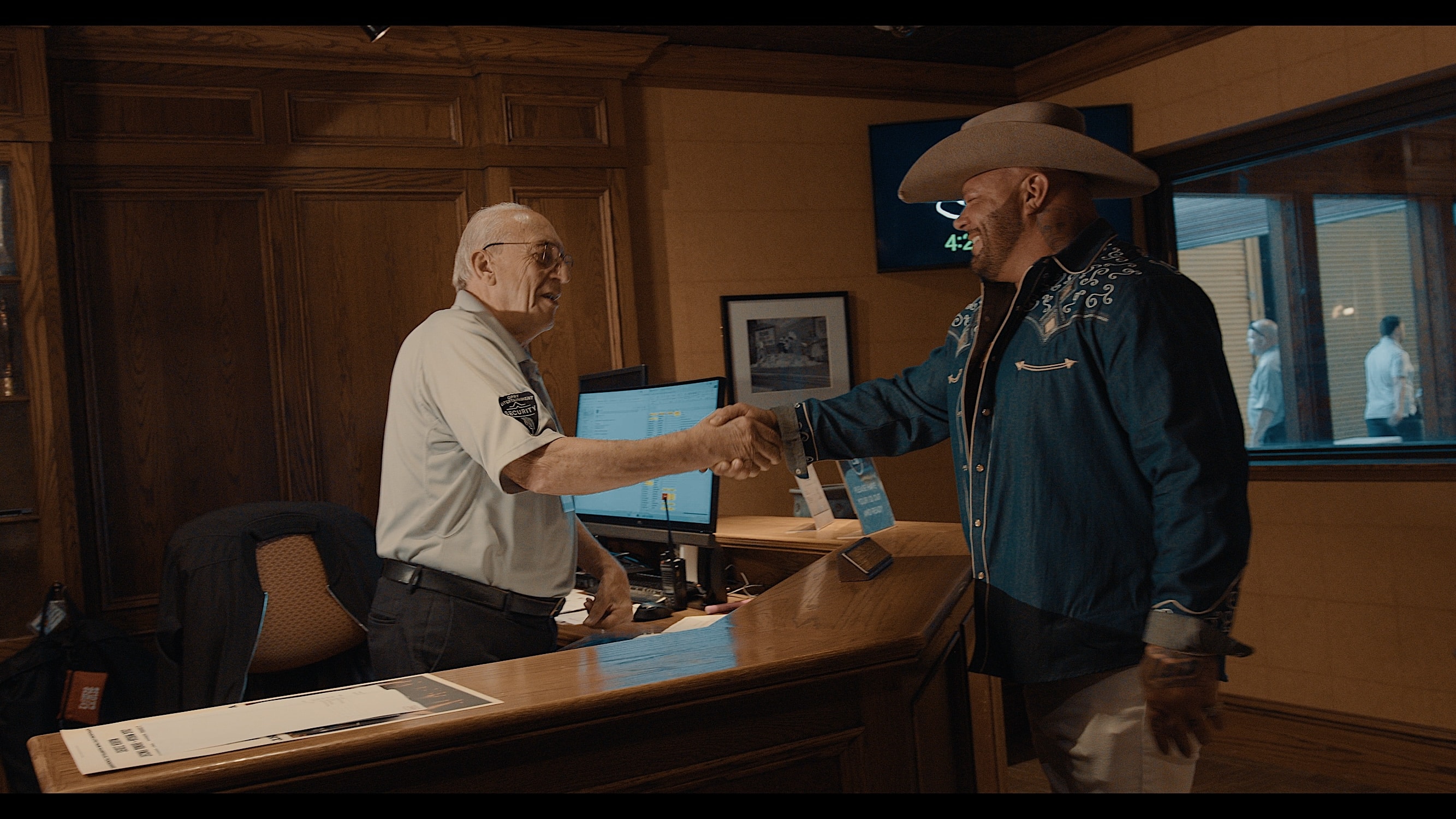

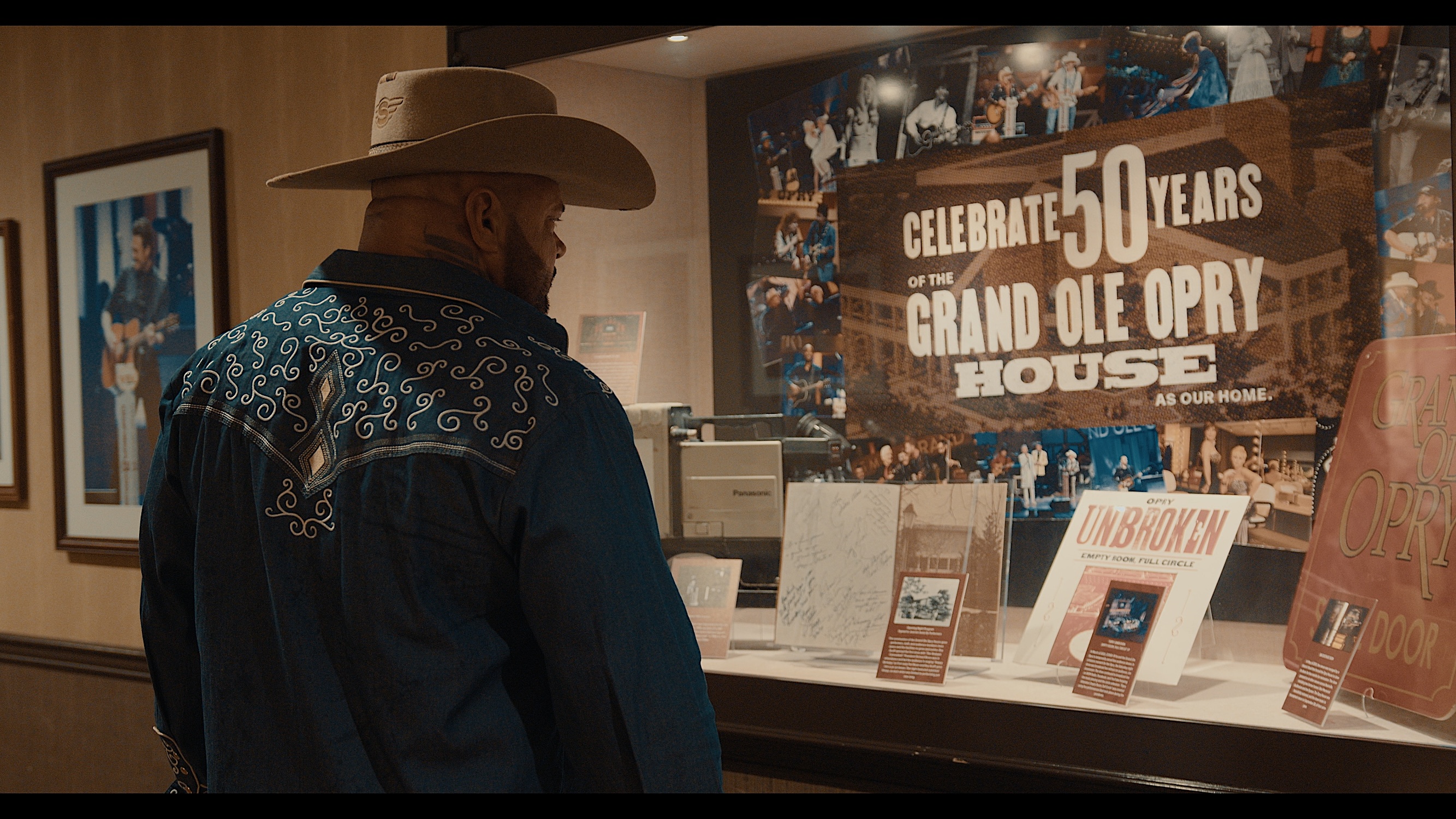

Between the two of you, you’ve sold out shows, charted, gone gold, and played the Opry. Yet you still carry this working-class chip on your shoulders. Is that something you’ll ever let go of—or is it the fire that keeps you moving?

It’s the fire that keeps me moving. You know I still live check to check. Even though I’ve had some incredible accomplishments in life, I’m still independent. I started an independent label and put a lot of money behind some other artists, got seven kids and a very big family, and an extended family. I take care of a lot of people, and I still have a lot of family that’s still blue collar, and you know, going through hard times. A lot of family that are still, you know, trapped in poverty and working nine to five just keep their head above water, so I don’t think that I ever really let go of that. I mean, even if I got super rich, I would still spend all the money taking care of the ones that I love and helping them get out of the holes that they’re in.

Finally—if Waylon and Willie were sitting here listening to 1976 with you, what do you think they’d say about how you’ve carried that outlaw torch forward?

I think my grandpa would be proud of me for sure you know one of the things he just always always really burnt into my head was stick to your guns be yourself don’t stand in my shadow find your own light he was big on being authentic telling your story and being true to your roots and taking care of the people you love so I think he’d love the album I think he’d be super proud of where I’m at right now.